A Pervasive Impression of Our Depravity: William T. Vollman’s Carbon Ideologies

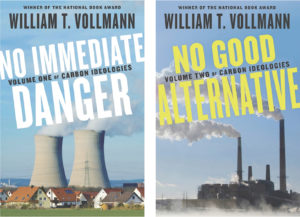

Those looking for hope (or even energizing desperation) about our prospects for dealing with global warming will want to avoid William T. Vollmann’s new two-part Carbon Ideologies series: No Immediate Danger: Volume One (624 pages; published in April) and No Good Alternative: Volume Two (688 pages and published in June). Vollmann is so pessimistic about our prospects that he wrote the books to an “unknown reader from the future” who lives on a planet deprived of our climate-warming, quotidian luxuries (“Confess it, reader: Don’t you wish you could have what I did?”) and who suffers the environmental consequences of our “luxurious selfishness” (“You from the future who must worry about heat-stroke and dehydration”).

Thematically, Carbon Ideologies has two goals. The first goal is to provide an explanation to our descendants on why more wasn’t done about global warming. As of this writing, the climatological consensus is that the earth is getting warmer and that this warming isn’t good for humanity. The twenty hottest years on record (i.e., since 1880) have all come since 1998. According to NASA, the only year hotter than 2017 was 2016. Yet for all the supposed alarmism about global warming, there hasn’t actually been much urgency. True, agriculture and industry have gotten more efficient. Farmers waste less water and cars can travel farther on less fuel. But there’s been no Manhattan Project for energy innovation. No New Deal for ecological justice. Renewable energies—wind, solar, biomass—have largely been researched and developed through private initiative and meagerly incentivized by the government only after extensive civic pressure.

In a short story from his 2014 collection, Last Stories and Other Stories, one of Vollmann’s characters laments how everyone “mentions the future so unemotionally. Why don’t they scream death, death, death?” We have a similar denialism and evasiveness when it comes to global warming—even from those doing the most to fight against it. Vollmann himself admits he’s “unable to comprehend in my bones that someday all our choices will probably run out.” Carbon Ideologies gives context and history to this psychological disbelief.

Vollman’s second goal in Carbon Ideologies is related to the first but intended for those of us around today rather than in the future. The two volumes provide a sociological investigation into our energy ideologies, specifically those of nuclear and fossil fuels. (“Solar,” Vollmann writes, “is an ideology of hope—not my department.”) It’s an investigation into “assertions,” “embellishments,” and “tautological twaddle” of these ideologies: how they appeal to people. Do they, for example, promise greater national sovereignty? (Yes, they all do.) More jobs? (All do.) Or that they’re better for the environment than the alternatives? (Again, all do—even coal.)

Vollman’s second goal in Carbon Ideologies is related to the first but intended for those of us around today rather than in the future. The two volumes provide a sociological investigation into our energy ideologies, specifically those of nuclear and fossil fuels. (“Solar,” Vollmann writes, “is an ideology of hope—not my department.”) It’s an investigation into “assertions,” “embellishments,” and “tautological twaddle” of these ideologies: how they appeal to people. Do they, for example, promise greater national sovereignty? (Yes, they all do.) More jobs? (All do.) Or that they’re better for the environment than the alternatives? (Again, all do—even coal.)

One way Vollmann got answers to these questions was by traveling to places where nuclear or fossil fuel is under particular scrutiny. He visited Japan multiple times after its “3/11” disaster (when a 2011 earthquake and tsunami hit the country within thirty-five minutes of one another, killing thousands and causing multiple nuclear reactors to melt down), tracking the country’s subsequent attitude and policy toward nuclear energy. He also visited the United Arab Emirates, where migrants work oil refineries while living in labor camps; Bangladesh, where locals were fighting against transnational corporations and their own government over a coal-mining operation that would displace upwards of a million people; and Appalachia, where he experienced West Virginia’s passivity to coal interests and decline due to…well, as Vollmann registers, people can find a lot of scapegoats for those actually responsible for the decisions. “Business is business” is a phrase he hears again and again during his carbon tour—even from those who lost jobs or loved ones or who’d been poisoned or maimed by those very decision makers.

To be done right, however, Vollmann’s investigation couldn’t just be a travelogue. It also needed to include extensive research. And that it does—perhaps too much, in fact. Vollmann seems to have read everything ever written in favor of (or in defense of) nuclear and fossil fuels—from children’s books on uranium to 1970s Japanese editorials on the safety of nuclear energy to 1960s biology textbooks already warning that the “warming up of the earth” will happen because of the “rapid, very voluminous release of CO2 by man-made combustions.” There are almost one hundred pages of definitions, units, and conversions, including what a “terrawatt-hour” is (“Power consumption, measured in terawatts [trillion of watts] consumed in an hour”), why “radiative forcings” (“Influences on global temperature”) are hard to measure, and how much coal is used to make a laptop (660 pounds—627 of them just for making the silicon chips).

Carbon Ideologies was originally supposed to be just one book, but due to the original manuscript’s length, Viking (Vollmann’s publisher) decided to split it into two volumes, with citations available only online. Vollmann is known for writing big, intimidating books. He wrote a seven-volume treatise on violence (Rising Up and Rising Down) and a series of historical novels on the settler-native conflicts in Colonial America (Seven Dreams). Even his standalone books are borderline unapproachable. Europe Central, which won the 2005 National Book Award for fiction, is over 800 pages of rambling prose and narrow margins. Imperial, his journalistic study of migrant workers in Imperial, California, is close to 1,200 pages (although that shouldn’t deter anyone from reading it).

Vollmann told me over the phone that he doesn’t “take kindly to cuts to [his] books,” that for him, “a book is like a child” and that editorial suggestions are like someone saying his daughter should be taller or have different colored eyes. Nonetheless, some of his books would’ve benefited from editorial trimming. And that’s certainly true for Carbon Ideologies. Both volumes are wordy and self-referential. Vollmann is an honest writer—playfully, exhaustively honest—so he’s always telling the reader what he does and doesn’t know. And how he came to know what he knows. And how he’d know more if he’d just had more time or money or resources or all of the above. This can be fun when the subject is something frivolous like music festivals or cruise lines but can feel out of place when the subject entails possible species extinction.

There are also too many facts in Carbon Ideologies. I realize this is an odd thing to say about a book series on such an important issue—an issue that is at once technical and political, massive in scale and meticulous in nuance. But there are simply too many parcels of information in Carbon Ideologies that contribute nothing except to be illustrations of the messiness and grandiosity of global warming as both an empirical reality and a political problem. Details crowd out structure. Concepts crowd out arguments. Trivia crowds out story. What Carbon Ideologies lacks in precision it tries to make up for in perseverance, but a lot of the facts included seem to be there for no other reason than because Vollmann (or a research assistant) went through the trouble of looking them up.

Vollmann’s mosaic of facts wouldn’t be as much a drawback if they didn’t take attention away from what are by far the best parts of the books: that is, the conversations Vollmann had during his travels, the sensitive histories he gives of the places he visited, and the moral impressions those conversations and places have made on him. It’s these parts that make Carbon Ideologies a unique, lasting, definitive contribution to the global warming literature.

In the series, each energy ideology has a corresponding geographical location (or locations): nuclear, Japan; oil, the United Arab Emirates and Mexico; natural gas, Colorado; coal, Appalachia and Bangladesh. As Vollmann notes, not all these energy ideologies are the same. For example, coal and nuclear feel under existential threat (and respond accordingly) while oil and gas don’t. Nor is each energy ideology the same everywhere. For example, conflicts over coal play out very differently in Bangladesh than they do in West Virginia. In Bangladesh, when Vollmann was there, locals of the country’s Phulbari subdistrict were resisting a coal-extraction project because most of the project’s produce and profit wouldn’t be controlled or gained by Bangladeshis. Instead the coal was to be owned and exported by Asia Energy (an Australian-registered, British-located, American-financed mining company). Bangladesh is still very poor—only 60 percent of the country has electricity (compare that to the global average of 85 percent). So locals wanted the coal used for native consumption rather than for transnational profiteering.

Although the coal-extraction project would poison water supplies, damage local agriculture, and dislocate upwards of a million people (not to mention pump more carbon into the atmosphere), Vollmann struggled to find locals who were against it for any reason other than it wouldn’t be under local control and used for local benefit. Most Bangladeshis Vollmann spoke to weren’t even “familiar with the concept” of global warming. And local authorities who were familiar with it justified the negative effects of the project by saying their meager little coal mines wouldn’t be nearly as bad for the environment as what China and the United States do. Vollmann hears this defense just about everywhere and for every industry. What good does it do to stop burning coal if China doesn’t stop also? Why should we shut down our nuclear plants if Japan isn’t going to shut down theirs? In other words, the rationales of civilization are becoming suicidal.

Sadly (but not surprisingly) Bangladesh’s government eventually got violent with local protesters. Police, army, and border patrol were called in: they killed people. In response, protesters set fire to Asia Energy company houses and smashed up some of the company’s drilling and transportation equipment. Then came a truce—the typical truce between protesters and a government aligned with the interests against its own people. Much was promised: no Asia Energy, no coal mining without local consent, justice and memorials for the murdered. According to Vollmann, none of the promises were kept.

In contrast to Bangladesh’s organized resistance and global-warming ignorance, West Virginia is disturbingly subservient and, in Vollmann’s vivid phrase, “aggressively miseducated.” Either West Virginians don’t believe the world is getting warmer; or, if it is, humans have little to do with it; or, if we do, there’s little the US alone can do to lower carbon emissions (those pesky Chinese again); or, if none of that works, that God will sort things out—apocalyptic hope being a central tenet of the religiously moribund.

Coal’s control over West Virginia comes across in Carbon Ideologies as pitiless and absolute. State functionaries get their scripts from the National Coal Association. There are coal festivals that crown coal queens and coal princesses. Students write letters to their local paper defending mountaintop removal. Governors brag about the “dramatic decrease in workers’ compensation.” Coal is seen as not only a prosperous industry (a former miner told Vollmann that in a good year he used to make a hundred thousand dollars) but as the centrifugal component to the West Virginian way of life. Mining embodies West Virginia’s self-image: the work is hard, dirty, and dangerous—but necessary. There’s also a cultivated link between miners and soldiers; memorials for dead miners refer to the “sacrifice they made for the country.” Vollmann passed an American Legion with the message, “We support the veterans. Keep the coal burning,” painted on it.

Beside the pride and resolve of West Virginians is also paranoia and victimhood. Like the linkage between miners and soldiers, these are cultivated by the “regulated community” (i.e., the businesses regulated by environmental protections). West Virginians are cautioned that coal is under attack and therefore so is their way of life. During the Obama administration, the president and his Environmental Protection Agency were the baddies (along with “left-wing activists”). Burdensome, unnecessary regulations were imposed on West Virginia, which is why coal’s share of the energy market declined in those years. (Obama-era fracking was actually the culprit, but to admit that would’ve been too distressing for the coal companies.) President Obama is thought to have imposed the regulations either because he was ideologically opposed to coal or because he was opportunistically opposed to West Virginia coal—preferring that, if America was going to extract coal, it should be done in the coal basins of his home state of Illinois. Fortunately for West Virginians, the new administration’s well-pampered EPA director, Scott Pruitt, promised Appalachia last fall that the “war on coal is over.” Even so, real and imagined enemies still lurk along the mountainsides.

Almost half of all carbon emissions come from coal. So in 2009 when atmospheric scientist James Hansen said, “Coal is the single greatest threat to civilization and all life on our planet,” he was perhaps wrong in sensibility (civilization seems to be doing just fine destroying itself) but correct in his assessment of coal as a uniquely harmful fossil fuel. But when West Virginians hear “coal,” they don’t think acidified water and rising temperatures. They think of the company dentist. And the annual family vacation. And the food on the plate and the lights in the house. About how West Virginian coal fueled the American industrial and military machine that won World War II. And about how coal offers not only a livelihood but a sense of identity and purpose. “Please blame our workers less than the rest of us. They sold their sweat for smoke, and we bought their smoke for the sake of our marvelous toys,” Vollmann writes. “Their strenuous, risky lives deserved to be celebrated by poets.” But instead their lives are exploited by bosses and ideologues—which is something they have very much in common with soldiers. Like the politicians and generals who know to insinuate that criticism of war is criticism of those fighting it, coal executives know to insinuate that criticism of mining is criticism of those working the mines.

Almost half of all carbon emissions come from coal. So in 2009 when atmospheric scientist James Hansen said, “Coal is the single greatest threat to civilization and all life on our planet,” he was perhaps wrong in sensibility (civilization seems to be doing just fine destroying itself) but correct in his assessment of coal as a uniquely harmful fossil fuel. But when West Virginians hear “coal,” they don’t think acidified water and rising temperatures. They think of the company dentist. And the annual family vacation. And the food on the plate and the lights in the house. About how West Virginian coal fueled the American industrial and military machine that won World War II. And about how coal offers not only a livelihood but a sense of identity and purpose. “Please blame our workers less than the rest of us. They sold their sweat for smoke, and we bought their smoke for the sake of our marvelous toys,” Vollmann writes. “Their strenuous, risky lives deserved to be celebrated by poets.” But instead their lives are exploited by bosses and ideologues—which is something they have very much in common with soldiers. Like the politicians and generals who know to insinuate that criticism of war is criticism of those fighting it, coal executives know to insinuate that criticism of mining is criticism of those working the mines.

Vollmann asks many tough questions in Carbon Ideologies. One of which is, “Who is the enemy?” He finds no winning answer. Can anyone really be singled out? Can the West Virginian be blamed for taking pride in his or her state’s suffering past? Or the coal miner for wanting a decent life for his or her family? Or the Bangladeshi who wants air conditioning? Or the Japanese who want a domestic energy source? Or even the fossil fuel executives? (The executives who would talk to Vollmann impressed him with their knowledge and common sense—he also understood their cornered-dog mentality. “I wouldn’t like it if someone said, ‘Well, Bill, we’ve decided writing books is really, really terrible, and we despise you for it.’”) Even professional skeptics are given the benefit of the doubt. After all, the debate over global warming is “subtle, tedious, and subject to revisions without end,” Vollmann writes. “We can hardly deny that the future is semiopaque, rendering consequences unknowable and therefore susceptible to good faith disagreements.” Vollmann, does, however, get annoyed with the cowardice and euphemism of energy companies. Many of his inquiries, particularly to Bangladeshi and American companies, are either ignored, evaded, or responded to with simply “no comment”; and companies use cryptic language like “removal of overburden” for blowing off the tops of mountains or “adjust operations” for taking away people’s jobs.

But if there are no enemies in Carbon Ideologies, there are plenty of villains. Namely, all of us. “I’m one of the villains and so are you,” he told me, adding: “I’m probably a worse villain than you because, having educated myself about how awful this is, I’m still doing it.” (We were talking about carbon emissions from commercial air travel.) And, he writes in Carbon Ideologies, “I pretended to come out against ‘waste.’ But can I honestly claim that prepackaged foods trucked to me at ever greater distances, with their energy-intensive plastic shells then gloriously thrown ‘away,’ did not give more time and means to love whatever I wished?” When he calculates the carbon emissions he was responsible for on a business trip, he semi-ironically, semi-despondently excuses himself because on the trip he “saw [his] mother and also slightly advanced [his] career.” When he discovers that for every pound of nylon produced, ten and a half pounds of carbon are released, he shrugs and asks himself whether discovering that fact will likely change his behavior: “Was I supposed to stop cleaning my toilet with that inexpensive nylon bristle brush?”

Our lives are filled with conveniences (ovens, washing machines, refrigerators—nylon) and we have come to expect an unlimited supply of energy for those conveniences. When we flick a switch, we’re not surprised when the light comes on. China and India—the world’s two most populous countries—want those conveniences also. And who are we to moralize about how for the sake of the planet they shouldn’t have them? Americans make up 4 percent of the world’s population, but we’re responsible for 15 percent of the carbon emitted every year. In comparison, China is 19 percent of the world’s population and responsible for 30 percent of carbon emissions; India is 18 percent of the population but responsible for only 7 percent of emissions. Those who defend fossil fuels say the choice is between economic development or ecological cleanliness. If they’re right—and China’s and India’s per capita carbon numbers approach ours within the current energy economy—Carbon Ideologies’ pessimistic tone will have been well merited.

Or perhaps global warming is just a hoax—or another case of collective hysteria. Wouldn’t that be nice? Regardless, Carbon Ideologies is an excellent investigation on the pathetic madness of how we presently do things—who actually makes the decisions, who’s most affected by those decisions, and who gets blamed when those decisions don’t work are all literally the opposite of what any reasonable society would have them be. As Vollmann writes to his doomed future reader:

Our self-serving ploys, and the low cunning of certain high executives, the apathetic greed of the horridly named “consumers” and the cynical short-sightedness of those who served them, the nationalistic loyalties of the irradiated Japanese and much-abused patriotic religiosity of West Virginians, the ignorant desperation of Bangladeshi activists, the unhealthy toil of guest workers in the Emirates and the gleeful stupidity of adversarial political systems under which a politician would squander a planet in order to distinguish himself from the incumbent, all these I have now presented to you, leaving (I suspect) a pervasive impression of our depravity.

Vollmann is correct. His books do leave a very pervasive impression of our depravity. As he told me over the phone, he wanted his future reader to wonder, “Would I have done any better?” and after reading Carbon Ideologies conclude, “probably not.”