White Privilege and Humanist Leadership

As progressives, humanists are a feisty, opinionated lot. My new book, The Best of the Humanist: Humanist Philosophy 1928–1973, shows this to be true from the beginning of the movement. For example, a contested question in the early days was whether humanism is a religion. Humanism has become more secular since then, and other questions have pushed to the fore. With the surge of feminism and the civil rights movement, the humanist movement has grappled with diversity, including in terms of leadership.

Most of the authors in The Best of the Humanist are cis straight white men, and the membership and leadership of the humanist movement today is predominantly white. So while white women have been able to become leaders in the movement, leaders from other racial and LGBTQIA+ groups (hereafter “marginalized groups”) have made little progress. White humanist leaders willing to change can help effectuate today’s recognition that more diversity is needed in the humanist movement’s leadership. This essay speaks to them.

Theoretically, humanists can handle it. The Best of the Humanist outlines a philosophy of radical acceptance of reality and truth applied to self-criticism with the goal of self-actualization of each individual. The thought process and the humanist values set forth are designed to mirror the capacity for change and resultant change that occurs in nature. The very nature of the philosophy calls for building a diverse humanist movement. That core construct sets humanism apart from most other secular viewpoints.

But humanism is a movement of individuals. Diversity is always present, the question is to what degree. The mostly white authors no doubt marveled at the diversity of thought published in the Humanist magazine in their time. They debated civilly, because the goal was truth in all its glory.

Truth can be an amazing, even elegant end, but the truth can also be messy. Maybe we’ve let physicists and chemists spoil us. They came up with simple formulas representing stunning relationships in the physical world; e=mc2 and H2O are reasonable, significant descriptions of parts of the natural order in that they aren’t characteristic of most of that order. In the human realm, everything is far more complex and, like I said, often messy.

Humanists need to embrace the complexity of most human interaction. Elegant scientific truth is a part, but only a part, of our interactions. Personal truth, in the form of personal experience, is a huge part of the complexity. The rest is comprised of our humanist values.

PERSPECTIVE

The Best of the Humanist covers philosophical writings from before the first Humanist Manifesto to the publication of the second in 1973. Comparing just those two manifestos reveals a wide range of values. And of course, change. And the change most needed today in the humanist movement—to advance diversity—is the hardest because it’s personal. This means that many humanist leaders will have to change their perspective, including on some things they hold dear. I know from personal experience.

Decades ago, during college, I was a political activist and was hired by a Chicano (Mexican and Mexican-American) student group to help bring the group’s demands to the university administration. The group’s leadership made clear that my job was to help them obtain what they wanted, not what I might think they should want. They listened to what I said about their ideas and how to approach administrators, but, as it should be, only their goals mattered.

What people initially think of others and what they want involves what Daniel Kahneman and others call “fast thinking.” Fast thinking results from internalized facts and conclusions, sometimes learned from parents, sometimes derived from serious thought. It’s the cognitive mechanism usually responsible for perpetuating prejudice. It can prevent you from actively supporting what another leader wants or even lead you to unconsciously resist it, not to mention think that you know better than someone else. To an aspiring or fellow leader from a marginalized group, these come off as opposition.

The first milestone is to consciously catch racist or sexist I-know-better-than-you thoughts in your mind, so that you apply slow thinking before acting on or expressing them. Essentially, attention paid to the sensibilities and sensitivities of other persons is paying off. As Kahneman and others have established, “slow thinking” is interrupting your fast thinking, giving you a chance to rethink judgments or impulses that you no longer want to validate consciously.

Rethinking your initial reaction is the next step of slow thinking. As an everyday example, when another driver recklessly cuts you off in traffic, slowing thinking can interrupt the immediate impulse to give the other driver a piece of your mind, which allows you to consider other options and likely decide the impulsive one isn’t worth it. Slow thinking is hard work when what’s at stake matters a lot, because it deliberates over all evidence, questions all values brought to bear, and challenges all prior conclusions about the question at hand. To truly understand what someone else wants takes a lot of slow thinking, because wants are almost always complex. That brings in the messiness that I’ve mentioned. Working on someone else’s goals inevitably entails many successive conversations about the details. My experience is that the most successful path to understanding is to ask direct questions rather than try to interpret those goals on my own. Some readers will recognize this approach as basic to personal relationships. Quite simply, approach questions of justice in humanism as you would your most personal relationships.

In thinking slowly about the goals of a potential humanist leader from a marginalized group, consider your own experiences. Even qualified cis straight white leaders have experienced injustices and hardships from which they can gain insight into injustices suffered by leaders from marginalized groups. Having experienced harassment, abuse, or poor health can serve that purpose. Being humanist, too, can at times lead to a sense of being marginalized. Whatever the source, associating one’s own experiences of what amounts to unfairness can help a relatively privileged individual empathize with and understand someone who has regularly experienced much harsher injustice. At the same time, each person’s experience is unique. Always remember that you can never know better than the other person what that person’s experience means.

Those and more advanced techniques are an essential part of being able to appreciate the different perspectives of those who don’t have the social privileges of cis straight white men and women. Certainly, understanding those perspectives is important in itself. I’ve found it key to fully supporting another leader from a marginalized group. More on point, changing your fast thinking can truly help you appreciate various forms of injustice. For example, that kind of appreciation led me to argue during the Iraq invasion and occupation that the US would never win over the Iraqi population so long as the US military did not give equal weight to testimony by Iraqis as testimony by Americans in the court-martial of a rogue US soldier.

INSTITUTIONAL POWER

To help individuals from marginalized groups exercise power in the humanist movement, changing your perspective is just the first step. While the following experience occurred when I was only a college student, I have encountered similar situations at subsequent points in my life. The lessons I learned have stayed with me.

As part of my extensive work in student government on campus, I was a leader of a progressive political party, Students for Positive Change, comprised of a coalition of progressive groups. I drafted and shepherded to party approval a policy for selecting candidates for elected office in the student government. If multiple candidates presented themselves for nomination to a particular elected office, any who were female or from a marginalized group would receive preference under the policy. The policy was the party’s expression of its commitment to diversity and development of leaders in those groups. We especially wanted candidates from marginalized groups to run for senate, the student government’s equivalent of a board of directors.

As part of my extensive work in student government on campus, I was a leader of a progressive political party, Students for Positive Change, comprised of a coalition of progressive groups. I drafted and shepherded to party approval a policy for selecting candidates for elected office in the student government. If multiple candidates presented themselves for nomination to a particular elected office, any who were female or from a marginalized group would receive preference under the policy. The policy was the party’s expression of its commitment to diversity and development of leaders in those groups. We especially wanted candidates from marginalized groups to run for senate, the student government’s equivalent of a board of directors.

In preparing to select our party’s candidates for the upcoming election of president and vice president of the student association, I—a cis straight white male—and a cis lesbian white female expressed immediate interest. We had both held seats in the student senate and worked hard as staff for the association. We were also party insiders and had developed an extensive plan for future work by the association if our party won the election. Many party activists strongly encouraged us.

Students for Positive Change reached out to groups in the coalition to announce the nominating process for our party’s candidates. At the nominating meeting, a woman who was president of the campus association of African-American students expressed her interest in nomination for the executive offices. Under the diversity policy, the two female candidates had preference.

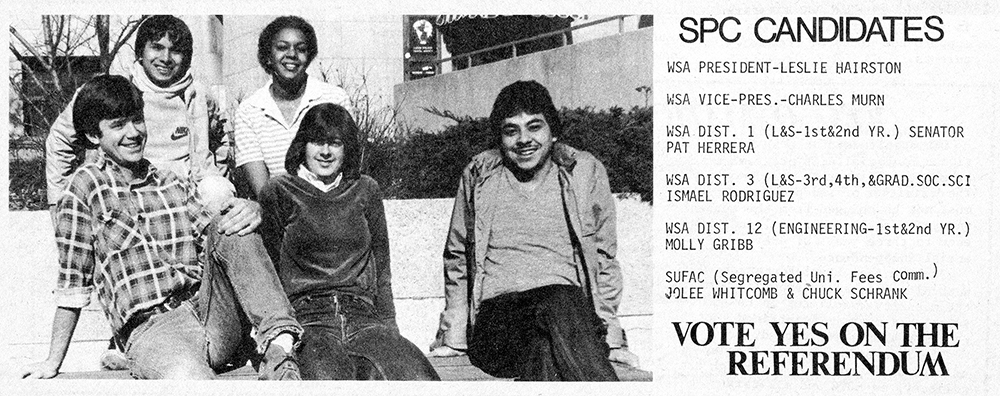

The year after the events depicted, Charles Murn (top left) ran on a ticket with Leslie Hairston (top right) representing the Students for Positive Change party.

In my fast thinking, I remembered that the diversity policy had been written with candidates for senate in mind, not executive offices. That all the plans I had helped form for confronting the university and for organizing in the academic departments would likely be undertaken by somebody else. In my fast thinking, I noted that the candidate from the African-American student group had no experience in student government.

Thoughts like this may seem innocent or even rational, but they are characteristic of fast thinking that’s at the core of white privilege when it comes to sharing power with leaders from marginalized groups. My privilege gave me access that I had used to great effect. The feeling that I was entitled to move up the ladder because of that effect would continue to block the access of leaders from marginalized groups. The only way to break that repetitive injury was to not insist upon my own continuing access.

Other veterans of the student senate also felt that lack of experience made the candidate from the African-American group a poor or undeserving choice. Other party insiders felt her lack of involvement in building the party made her undeserving. They all started messily fighting her supporters over her nomination.

Perhaps my family’s frequent moves when I was a kid helped: I learned to disconnect from what I had expected despite the emotional distress. So I stepped back to, in effect, think slowly. I totally let go of my prior perspective, in order to assess a brand new situation. It was hard. But I did it.

Thinking slowly, my commitment to justice offset my distress at my own impending loss. I was no more entitled to the nomination than anyone else. That I wasn’t specifically thinking about the executive offices when I promoted the diversity policy was irrelevant. I had, in fast thinking, assumed that having worked in the student government and in the party was the most important qualification. The new candidate may have lacked that qualification, but the other woman on the ticket had it. I had weaknesses, too. The new candidate deserved the opportunity, and she had done enough in her organization to overcome any doubt about that. The fact that Leslie Hairston has since served on the City Council of the City of Chicago, Illinois, for nearly two decades vindicates my conclusion. I like to think that her experience running for president of a student body of more than 40,000 students was good preparation for getting and staying elected ward alderperson. I came out in favor of having the two women on the ticket for the executive offices of the student government.

The story didn’t end there. I pulled myself out of the nomination race, ceding power to qualified candidates. But one cannot assume how things will turn out because, as I hinted above, guesses about what other people want are often erroneous. When a raucous party meeting considered the combined ticket of the two women, those advocating application of the diversity policy nonetheless acknowledged the importance of work in the student government and to challenging the university administration. In short, the majority decided that I should be put on the ticket in place of the cis lesbian white woman.

Along with others, I opposed that effort. It flew in the face of our diversity policy, and so I refused to accept that nomination. By then, the process had gotten so personal that the cis lesbian white woman withdrew. She felt personally attacked and wasn’t willing to work with the people proposing her replacement. (She went on to receive the party nomination the following year.) When she assured me even a couple days later that she wouldn’t run, I realized I had a brand new situation to assess.

In fast thinking, I was appalled at the deviation from the affirmative action policy I had written. In slow thinking, I saw that alternative strategies available to me would likely have worse results. I recognized the effort as a sign that people from marginalized groups who promote their leaders want both success and diversity, too. The majority in my party wanted me on the ticket to increase the chance of winning. I agreed to be on the ticket.

Despite our best efforts, we lost some of our members supporting the insider ticket, as well as some who disagreed with the removal of the cis lesbian white woman. Unsatisfied editors of the progressive student newspaper endorsed me, but not my running mate. While she and I campaigned hard with our willing party members and other supporters, we couldn’t overcome energized opponents in the final election.

That brings me to one final lesson regarding institutions for the humanist movement. For the good of the movement, whether you gain the leadership position you seek or not, humanist leaders (and membership, too) need to get fully behind whoever rises from our collective efforts to promote qualified leaders from marginalized groups to leadership positions.

PERSONAL POWER

Recognizing that leadership in humanism is not zero-sum is essential. That principle has been central to my attitude about all leadership opportunities since my college political party experience. I strongly urge all cis straight white male humanist leaders (and women who feel so inclined) to adopt it. It has allowed me to follow my desire and ability to help by leading, while giving every opportunity to individuals from marginalized groups who step up to lead.

The easy case is a leadership position that interests you but not anyone from a marginalized group. Even competing against other cis straight white men to get such a position presents no question of power balancing.

Where a reasonably qualified person from a marginalized group is seeking a leadership position that interests you, you have the opportunity to empower that person. You face a choice similar to my experience so long ago. For you to forgo your interest in the position in question, you have to let go of your expectations about that specific leadership position. An important part of doing that is consideration of alternatives.

I recognize that my privilege always gives me more opportunities and makes it easier for me to succeed at them, and established leadership positions are inherently easier and more desirable than building something new. With white (male) privilege comes quicker acceptance, more support, and less resistance than an equally qualified leader from a marginalized group faces; not having to fear being stereotyped if I fail; and thereby having less to lose by taking the risks involved in innovating and exercising the creativity that we all have. By filling gaps that no one else is working on instead of pursuing existing leadership roles, I can be doubly useful—advancing the cause of diversity and either establishing new programs with humanist organizations or refreshing declining ones that are still priorities. My approach generates a win-win outcome.

As I have cased it, choosing the win-win course is a personal choice. Not all of you with white privilege will initially feel comfortable pursing this route. So I ask you to slow think it, and remember that other leaders in the humanist movement will welcome and support your choice of an alternative.

Being a humanist cannot simply be about claiming superiority over theists and those secularists who don’t espouse progressive values. It’s about change, and change is hard. In the old days I might have called up the saying “practice what you preach.” As a humanist I say: live your humanism. The humanism coursing through The Best of the Humanist: Humanist Philosophy 1928–1973 and through our foundation today. I urge all humanist leaders with white privilege to remember that by choosing the harder option—that includes ceding power—you will personally grow more than if you take the easier route and be able to work with talented humanist leaders with a wealth of amazing perspective, while together expanding the humanist movement faster. I can’t think of more important leadership by a humanist with white privilege. I can’t think of a better transformation of white privilege.