Target Practice Troubled Teens, First Person Shooter Games, and the US Military

Before Nikolas Cruz shot seventeen people dead and injured seventeen others at a Parkland, Florida, high school on Valentine’s Day, and before Dimitrios Pagourtzis killed ten and injured thirteen at Santa Fe High School in Texas on May 18, both had uploaded photos onto their Instagram accounts of their favorite pastime—the video game genre known as first-person shooter.

Both Cruz, age nineteen, and Pagourtzis, seventeen, were emotionally distraught because of girls who rejected their advances. They were both outcasts in their respective high schools. They both played video games that simulated war. In his Facebook bio, Pagourtzis showed interest in joining the US Marine Corps in 2019. Nik Cruz felt more at home with the Army.

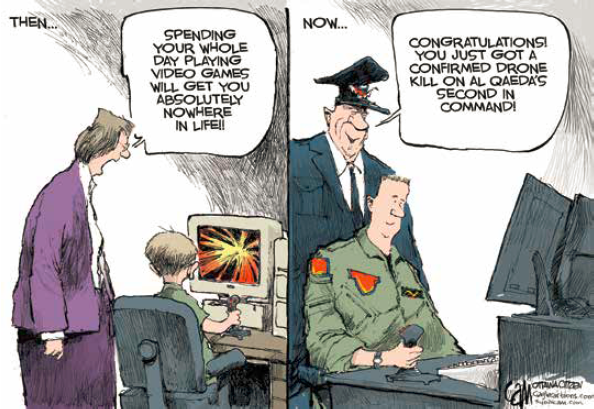

This is not a cheap shot. The military recruits gamers from the virtual world.

The video game America’s Army, a vicious first-person shooter game, has millions of avid fans and is one of the most frequently downloaded games. According to a study by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, “the game has more impact on recruits than all other forms of Army advertising combined.”

The military exploits the visceral appeal of virtual killing. More than that, the Pentagon seeks virtual shooters who have developed surprisingly complex strategic and tactical skills learned through thousands of hours of gaming experience. These skills are like those used in real combat.

The training division of the US Army Combined Arms Center has its own massive multiplayer role-playing game to train new recruits. (An MMRPG is an online game with a potentially unlimited number of players, each of whom plays a character in a virtual world.) The system, similar to World of Warcraft, allows individual soldiers around the world to log into the Army MMRPG and play as individuals or as units. Thanks to National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden, we know about a 2013 NSA document, “Exploiting Terrorist Use of Games & Virtual Environments.” We know the NSA and the CIA teamed up with the UK’s Government Communications Headquarters to deploy real-life agents into the virtual World of Warcraft and infiltrated Xbox Live with tens of millions of players worldwide. The world’s two top spy agencies can identify a labyrinth of social networks of those with the inclination for virtual killing. The targets of the espionage may be in Syria or Venezuela, Florida or Texas.

In World of Warcraft, players everywhere on earth share the same virtual world, walking, running, travelling around, and killing a variety of computer-generated monsters along with custom-designed human avatars that might be made by shooters 10,000 miles away. Pro Publica, a recipient of Snowden’s release, describes the action as:

killing computer-controlled monsters or the avatars of other players, including elves, animals, or creatures known as orcs. Players create customized human avatars that can resemble themselves or take on other personas— supermodels and bodybuilders are popular—who can socialize, buy and sell virtual goods, and go places like beaches, cities, art galleries and strip clubs.

Real and virtual are blurred.

SAIC, the defense contractor behemoth, has studied MMORPGs and concludes they can be used for a variety of purposes by America’s enemies, from recruiting members to training fighters to spreading propaganda—like the US does with America’s Army.

It’s ironic to consider the NSA may well have data on the gaming activity of both Cruz and Pagourtzis.

Pagourtzis also followed thirteen groups and individuals on Instagram, including groups like “sickguns,” “guns_fanatics,” and “guns.glory.” Together, the gun groups he followed have more than a million followers. The sites glorify weaponry and use slogans like “Feeding your Addiction,” “Gun Addict Approved,” and “Guns—I love guns—It’s as simple as that.” Second Amendment rights reign supreme while few challenge the notion that children should be exposed to these sites.

Pagourtzis had uploaded an image to his Instagram account of the first-person shooter game Silent Scope, which brings the sniper experience to virtual life. It has several competitors in the virtual sniper market and consistently receives high ratings. The game depicts the kidnapping of the president of the United States, his wife, and their daughter, to which the sniper must respond to save the nation.

Nine of the Instagram accounts Pagourtzis followed were fan pages for firearms. The four others included the official accounts for the White House, President Donald Trump, First Lady Melania Trump, and Ivanka Trump. He lived in a fantasy world of presidents and demons and avatars. He also lived in a real world of principals and parents and unrequited love. They’re too easy to confuse in a teenage mind.

Pagourtzis virtually killed

thousands and he was a hero. (Adam Lanza, the Sandy Hook shooter, racked up 83,000 kills.)

The virtual killing kept his mind off his social status at school and the emotional trauma of rejection by a pretty girl. He hated her for it and he wished her dead, along with her

terrorist co-conspirators. He could take them all out with a

brilliant strategy and carefully chosen tactics.

Pagourtzis virtually killed

thousands and he was a hero. (Adam Lanza, the Sandy Hook shooter, racked up 83,000 kills.)

The virtual killing kept his mind off his social status at school and the emotional trauma of rejection by a pretty girl. He hated her for it and he wished her dead, along with her

terrorist co-conspirators. He could take them all out with a

brilliant strategy and carefully chosen tactics.

Lt. Col. Dave Grossman offers a chilling indictment of violent video games in a widely circulated article published in Phi Kappa Phi Forum in the fall of 2000 titled, “A Case Study: Paducah, Kentucky.” In 1997 fourteen-year-old Michael Carneal fired eight rounds in fast succession at a high school youth prayer group, killing three and wounding five. Grossman writes,

I train numerous elite military and law enforcement organizations around the world. When I tell them of this achievement, they are stunned. Nowhere in the annals of military or law enforcement history can we find an equivalent “achievement.” Where does a fourteen-year-old boy who never fired a gun before get the skill and the will to kill? Video games and media violence.

Grossman argues that youth who pull the virtual trigger to slaughter thousands become hardened emotionally, calling these violent military shooting games “murder simulators.”

The World Health Organization (WHO) is set to include “gaming disorder” (defined as a disease characterized by impaired control over gaming) in a June update to its international classification of diseases. Millions may be affected, considering there are 2.2 billion gamers in the world.

The United States is unlikely to follow suit. After all, the US video gaming industry is a $36 billion business. It’s how things roll in America these days. Consider too that the gaming industry has twice the revenue of the gun industry, which has successfully resisted common sense measures to ban assault weapons.

The American Psychiatric Association has been studying “internet gaming disorder” since 2013, but there’s been no call to action. Rather than seriously examining how mental health issues and violent video gaming intersect, US policymakers are content to concentrate on strengthening some background checks and eliminating bump stocks.

Dimitrios Pagourtzis and Nikolas Cruz are products of American culture. Both were outcasts who took refuge in violent video games and the notion that guns are the great social equalizers because of the way they settle scores. In too many like minds, these two young men have relevance. They’re legitimate because they fought back. Because nothing really matters; human life is cheap and paybacks are hell. Game over.