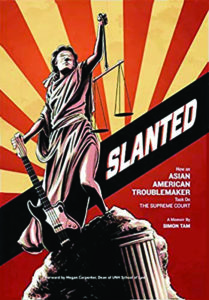

Slanted: How an Asian American Troublemaker Took on the Supreme Court

BY SIMON TAM

TROUBLEMAKER PRESS, 2019

326 PP.; $26.99

Debates on free speech nowadays tend to revolve around whether one should be free to call their Pakistani neighbor racial slurs without consequence or whether university students should be allowed to shout at guest lectures who pontificate on the mental health of transpeople and the mental inferiority of black people. Americans, we’re told, are not free to speak freely. We’re told this by people on television, podcasts, radio, magazines, and the country’s most-read opinion pages. For those of us who live in the “real world”—where aunts complain over quiche that George Soros is funding mass immigration and coworkers on our lunch break explain how the Confederate flag doesn’t symbolize “that”—we find the revelation that Americans are self-censoring particularly remarkable. Christ, what are you people thinking that you aren’t already saying?

Of course, this kind of speech—where you get to bully and blame the poor and the powerless—is quite well protected on the legal level, as those who spend all day shouting about being silenced admit, so they warn that it’s actually “the culture of free speech” that’s at risk. For example, the government won’t censor you, but your coworker can still call you an “a-hole.” No permit process can stop you from getting a public street blockaded so that you can shout “the Jews will not replace us!” but that doesn’t mean you’re safe from getting punched by a pedestrian afterward. And so, we’re still evidently on the verge of a free-speech apocalypse.

Other kinds of speech, however, are still censored more by government than by culture or community. All sorts of legal taxonomizing has been done so that banks have to make loan documents somewhat readable, executives can’t lie to investors about financial information, and doctors can’t tell a patient the MRI looked fine when it actually revealed a tumor, even though all these scenarios could plausibly be constitutionally protected under free speech. The government censors speech in all sorts of mundane scenarios like these, usually to protect “national interests” or to keep the economy running smoothly (or at least as smoothly as possible). And it’s in these scenarios where debates on free speech are both theoretically and practically most interesting.

Simon Tam

Asian-American musician Simon Tam’s memoir Slanted (published in March) centers around one such scenario. Tam wanted to trademark his band’s name (The Slants), but the federal Trademark Office said no because under Section 2(a) of the 1946 Lanham Act, the Trademark Office can deny requests for trademarks that it deems “scandalous, immoral, or disparaging.” Despite the fact that plenty of existing trademarks contain the word “slants,” the Trademark Office deemed Tam’s potential trademark “disparaging” because The Slants are an Asian-American band and their name obviously refers to the racial slur. In other words, as Tam himself points out in Slanted, the band couldn’t get their name trademarked because of their ethnicity. Tam submitted his first trademark request to the Trademark Office in March 2010, and it wasn’t until June 2017, when the Supreme Court ruled that Section 2(a) of the Lanham Act was unconstitutional, that The Slants was finally trademarked.

The Supreme Court victory was bittersweet for Tam. On the plus side, it meant he and The Slants’ other members had collective ownership over merchandise and licensing (a big money-maker for bands). On the negative side, it meant that the Native-American case against the NFL was legally irrelevant. It no longer mattered whether the Washington Redskins was “disparaging” or not; trademarks no longer had a moral standard. Tam’s victory had “seiz[ed] control of a racial slur, turning it on its head and draining its venom,” but it also destroyed the only weapon Native Americans had for getting Dan Snyder to change his team’s name. “The euphoria that I had expected,” writes Tam, “was replaced with dread and disgust. The press had reframed our struggle into a narrative around a racist football team.” (Tam quotes a few illustrative headlines about the media’s framing of his Supreme Court victory: “Washington Redskins Win Supreme Court Decision,” “Redskins Score Major Victory in Supreme Court Case,” and “Offensive Speech Now Ok Says Supreme Court.”) Tam is accused of “enabling people like Dan Snyder to profit from racist imagery” and of “being a native-born person of color perpetuating the work of colonizers.” All Tam wanted was to “take back” a racial slur, not be the legal fracture point between minority groups.

The fundamental question is: Should trademarks have a moral standard? Those in favor say they should because that will stop the government from working on behalf of racist trademarks like the Washington Redskins. Those opposed, such as Tam, say it shouldn’t because the “price of censorship [is] often carried on the backs of the underprivileged.” Aunt Jemima, Chief Wahoo, and Black Sambo all were trademarked by large corporations, but The Slants couldn’t get their band name trademarked. Tam wants a legal system where “laws would be judged on their impact as well as their intention.” That way, in his perfect world, The Slants could have their trademark while Snyder would potentially lose his. Tam blames “white supremacy” for using his case to nullify the Native-American case against the Redskins; but what he calls “white supremacy” others would call “universal application of the law.” Tam is onto something when he says trademark registrations should take intent into account—which they do (or did anyway), as he tacitly confirms, when he notes that companies such as Perma-Chink have a registered trademark since the Trademark Office, presumably, determined that the company’s name had nothing to do with the racial slur. And, in the past, the Trademark Office had distinguished trademarks intended to abuse from trademarks intended to empower: N.W.A, for example is trademarked despite it containing a racial slur.

The Supreme Court ruled in Tam’s case that moral standards for a trademark are a violation of the First Amendment, and after the ruling the Trademark Office got the predictable trademark requests for racial epithets and Nazi paraphernalia. Tragically, Tam’s case made it so his preferred trademark laws, where intent matters, aren’t the law of the land. The Trademark Office can no longer make such distinctions.

A good deal of Slanted is skimmable (if not skippable). There’s a lot of romantic history and personal trivia that are unnecessary. (In a footnote Tam assures the reader that he knows how many Death Stars there have been in Star Wars—okay?) And while everyone wants to be the hero of the story, and memoirists are known to exaggerate, some of the praises and prejudices documented in Slanted just aren’t believable. Still, Slanted does what a good memoir should: it shows a person shaped by society—its laws, institutions, and mores—and how that person fought back to reshape society. The most important lesson Tam takes from his own story is that laws are a two-way street. They aren’t simply rules imposed from above. With enough money or volunteers, people can change them. It’s sad just how many of America’s social problems were organically part of Tam’s story, but impressive just how well he does at knitting them together: the conceptual incoherence of “race,” the history of anti-Asian bigotry, the role and purpose separation plays in assimilation for immigrants, the psychological conflict minorities have between just getting along and correcting stupidities, the prohibitive costs of justice in our legal system, and the nastiness of ethnic stereotypes in media. All are in Slanted and all are handled with more care and common sense than you›ll get from most professional political commentators.