CHURCH & STATE | If You Want Social Justice, Work For Church-State Separation

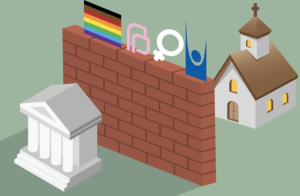

Take a minute and conjure up in your mind an image of a brick wall. Imagine that on top of that wall rest the issues you care about. Examples may be LGBTQ rights, women’s rights, abortion and reproductive freedom, equality for nonbelievers, public education, sound science, the right to be served by a business, and protecting the arts from censorship.

What would happen to all of the issues resting on the top of that wall if it were to collapse? You don’t have to be a structural engineer to figure this out: those issues would fall along with the wall.

That wall is the one that should separate church and state. And be assured that as it’s eroded, many of our other rights are threatened as well.

Church-state separation is a common thread running through many rights-based struggles these days. Consider the attacks on legal abortion that have passed or are pending in several states. They share some commonalities—one of which is that they’re motivated by conservative religious beliefs. Women are told they can’t terminate a pregnancy because that’s not what God wants.

In Alabama, politicians who backed that state’s extreme anti-abortion law didn’t even try to hide the religious impulses behind it.

“This legislation stands as a powerful testament to Alabamians’ deeply held belief that every life is precious and that every life is a sacred gift from God,” said Republican Gov. Kay Ivey as she signed the measure into law. A state senator who backed the bill, Republican Sen. Clyde Chambliss, asserted, “I believe that if we terminate the life of an unborn child, we are putting ourselves in God’s place.”

In Missouri, state Rep. Holly Rehder, also a Republican, explained her support for the state’s far-reaching abortion ban, which, like Alabama’s, lacks exceptions for victims of rape and incest, by saying, “To stand on this floor and say, ‘How can someone look at a child of rape or incest and care for them?’ I can say how we can do that. We can do that with the love of God.”

Missouri has a long history of using theological justifications for anti-abortion measures. In the late 1980s, the state passed a law stating that life begins at conception—a theological, not scientific, declaration.

We’ve seen the same religious arguments trotted out by fundamentalists as they’ve attempted to roll back LGBTQ rights. Prior to the US Supreme Court’s decision to uphold marriage equality in 2015, religious right activists cited passages from ancient religious tomes as if they had any relevance to secular law. The high court based its decision on the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause, but church-state separation was lurking just below the surface. After all, if you absolutely cannot articulate a secular rationale for a law and must point to the Bible or decrees from a religious leader to buttress the measure, it’s automatically suspect.

Recently, we’ve seen attempts to allow the owners of stores and businesses to deny services to members of the LGBTQ community and others or allow people working in the healthcare field to refuse treatment to just about anyone—again, all based on religion. Proponents may claim this is “religious freedom,” but it’s not. Religious freedom gives you the right to join (or stay away from) the house of worship of your choice, to read the religious texts of your choosing, and to share your views with others on your own time with your own dime. It gives you no right to deny others their rights, assail their dignity, or deny their very existence. Under a proper application of separation of church and state, this ersatz version of religious freedom must fail.

Conservative religious groups have a long history of trying to tell everyone else what to do. For a long time, they were successful. They curtailed Americans’ access to birth control; infused the public schools with their prayers and religious practices; blocked women’s rights; used repressive laws to keep LGBTQ people in the closet; and censored books, magazines, plays, and films until public opinion (and often the Supreme Court) made them stop. And the vehicle the court used to do that was usually separation of church and state.

While our federal courts may be lax on supporting the separation principle these days, that’s no reason to back down. In fact, it’s a reason to push back even harder and work through the political system for courts that once again firmly endorse the church-state wall.

Humanists’ traditional emphasis on church-state separation need not come at the expense of promoting social justice. It’s not an either/or proposition because those two concepts—church-state separation and social justice—are joined at the hip.

If you want social justice—for women, for members of the LGBTQ community, for nonbelievers and religious minorities, for the poor, and for racial minorities—you should work for separation of church and state.

Why? Because past examples of oppression were almost always tied to a culturally dominant hegemony that was white, affluent, conservative, male-centric, and Christian. Anyone who challenged this paradigm was accused of attacking faith, God’s law, and the natural order of things. For decades, arguments like this were used to keep people in their (God-ordained) places of second-class citizenship, poverty, and submission. Decoupling conservative theology from government power is the first step toward breaking those chains.

The religious right has stood against every advance of social progress this nation has witnessed. Humanists and others have led the push for the expansion of these rights in the face of entrenched opposition anchored in fundamentalists’ interpretation of ancient books that some deem holy. Change did come in many cases—and separation of church and state was often the instrument that made it possible.

I’m confident that humanists will continue to promote all forms of human rights, equality, and economic justice. But as we do so, let’s not make the mistake of assuming that we don’t have the bandwidth to promote church-state separation and social justice at the same time. Indeed we do as they are often one and the same.