Evangelizing: The Good, the Bad, & the Ugly

I have often been called an “evangelical atheist.” Technically, evangelism is the Christian practice of proselytizing, of bringing souls to Christ. But for the sake of argument I’m employing the looser definition—evangelizing as an attempt to convert people to another point of view.

I was raised an Orthodox Jew, and Jews don’t proselytize gentiles. That practice stopped in the fifth century, when the Roman Empire outlawed conversion to Judaism under penalty of death. But Jews do proselytize other Jews. One such early memory took place during a Shabbas (Saturday) walk in Philadelphia with my rabbi. When a man asked us where the nearest subway was, my rabbi in response asked him if he was Jewish. When the man acknowledged that he was, my rabbi refused the request because Jews are not permitted to ride on the Sabbath. My rabbi was “protecting” this Jew from breaking the law. Such a response was consistent with our weekly wait outside the synagogue on Saturday morning until a gentile passed who would turn on the lights for us. (Incidentally, Colin Powell was once a “Shabbas Goy” in New York.) There is no pretense in Judaism that such rules have anything to do with ethical behavior. We are simply separating our tribe from the gentile tribe.

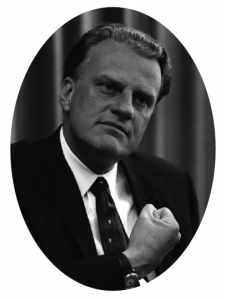

My first exposure to Christian evangelism was at a Billy Graham Crusade in the early 1960s. I was working my way through college by selling hot dogs and orange drinks at basketball games and other events at Convention Hall in Philadelphia. When I heard about the Crusade to be held there, I asked the organizers if I could sell my wares. The Christian organizers turned down my request, but they invited me to attend the event. I went and had a terrific time. Graham was a charismatic speaker who moved an audience in ways I had never seen before. At the end, he invited people to come forward. So I did, out of curiosity. After Graham mumbled a few words about being “saved” to those of us who came forward, nearby waiting pastors each chose one of us to indoctrinate further.

My pastor began by asking if I had accepted Jesus Christ into my life, to which I said no. Further attempts (fire and brimstone included) to close the deal were met with similar frustration for him. When he found out I was Jewish, he transferred me to another pastor with a Jewish background. I began the conversation with Pastor Two by asking if his parents were alive. After hearing that they had died good Jews, I asked how painful it was for him to know that his devoted parents were suffering the torments of hell. When he disagreed with my conclusion, I suggested we invite Pastor One into our conversation. The highlight of my evening was watching the two of them argue about the afterlife of Pastor Two’s parents.

I know I am in a distinct minority, but I decided after this first positive experience that being evangelized could be a lot of fun. I have since enjoyed inviting Jehovah’s Witnesses into my house, frequently to their surprise. More often than not, they leave before I am finished talking to them.

My wife Sharon and I were once invited to take a personality test at a Scientology storefront mission during a visit to Ann Arbor. After waiting for a few minutes of tabulation, we were given our results. Sharon passed, and was invited to join. Much to my surprise, I was told that my personality test revealed that I might not be a suitable member. I had even answered the questions honestly! Does anyone know of other Scientology rejects? Sharon received two years of increasingly more urgent mailed requests to become a Scientologist, until they finally concluded that her case was hopeless, too.

I later had a brief involvement with members of the Unification Church (otherwise known as Moonies). They were proselytizing on my College of Charleston campus, along with other religious groups, until campus authorities told them to leave because they didn’t have a faculty sponsor. I thought this ruling unfair, since the Catholics and Protestants had sponsors, so I offered the Moonies my services as their faculty sponsor. No religious test was required for the position, and they gratefully accepted and were allowed to proselytize on campus. When the Moonies asked about my views, I told them I thought their beliefs were bizarre and expressed the hope that they would fail to get any converts. Should I ever run again for political office, perhaps my Moonie support will be held against me. Or is it still worse to be an atheist?

The most memorable evangelizing I saw was in Papua New Guinea, where I spent six months in 1987 teaching mathematics at the university. Not only were most students the first in their families to go to college, they were the first to leave their village tribes. Our university evangelism consisted of persuading students not to continue their ongoing tribal disputes at the university. When I first arrived in PNG, I was told that if I had a serious driving accident, I should not stop at the scene. Instead, I should drive directly to the jail, where the police would protect me. The “payback” system in PNG allows for physical harm by a family member whose relative is harmed. If a member of Tribe A is killed by a member of Tribe B, a designated member of Tribe B may legally kill any member from Tribe A. If he kills more than one member, “payback” again kicks in. Fortunately, I never had a driving accident there.

Women were treated so poorly that PNG was the only country I knew where men outlived women. Village men typically resided in a house, while women and pigs (yes, pigs) lived in a shack behind the house. Both women and pigs were sold or used for barter, the woman/pig ratio depending on the quality of both the women and the pigs. Further, wife beating was perfectly legal and common.

Missionaries of all kinds lived in Port Morseby, where I lived too. Some tried to improve the lives of PNG’s inhabitants, usually accompanied by religious conversion. I could always spot Mormon missionaries from a distance. They, along with the U.S. ambassador, were the only ones I saw with ties and jackets. One PNG resident asked me which Christian club I belonged to. When I looked puzzled by his question, he told me he had joined the Catholic club because they gave him free food.

The Catholic missionaries deplored the “ungodly” practice of bare-breasted women. When I asked a Catholic missionary why he focused more on bare breasts than on wife beating, he said they couldn’t change everything that was wrong in the country and that breasts were a good place to start. There was once a university beauty pageant with five participants, four of whom were bare breasted. When I saw that the primary judge was a Catholic priest, I confidently predicted the winner to my colleagues (resisting the temptation to place big bets). After the breast-covered woman won, my colleagues showed an undeserved respect for my powers of judging beauty.

With so many examples of ugly evangelism, what should humanists do? Theist or nontheist, we are all evangelists for issues that matter to us. The question isn’t whether we should proselytize, but how and how often? Were I on the other team (soul saving), I would be embarrassed by a fellow believer who stood on a corner shouting epithets at sinning passersby. I think we shouldn’t be screaming atheists, nor should we go door-to-door spreading the word that there are no gods. But each of us has to decide our level of evangelism. Many of us are comfortable writing letters to the editor, participating in forums or debates, writing to members of Congress, or coming out of our atheist and humanist closets at appropriate times.

What I learned from my Billy Graham Crusade (though I didn’t realize it at the time) was that I am a counter-evangelist. I don’t usually initiate discussions with religionists, but I enjoy having them. I sometimes feel that I am as much on a counter-mission as they are on a mission. I generally counter-evangelize evangelists until either they or I see the discussion becoming counter-productive. There are many opportunities to make people aware of our position without trying to force it on them. For me, in a culture replete with religionists, engaging impassioned participants in a conversation they never had before is the best kind of (counter) evangelism.

But in the end, religious or not, silent evangelism might be the most effective approach for all of us. People are likely to respect our worldview more for what we do, than for what we preach.