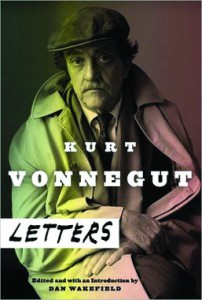

Kurt Vonnegut: Letters

In his study of the psychological damage wrought by World War II, historian Paul Fussell details a soldier’s view of death in combat as a “slowly dawning and dreadful realization” that begins with the rationalization: “It can’t happen to me. I’m too clever/agile/well-trained/good-looking/beloved/tightly laced etc.,” and eventually arrives at: “It is going to happen to me, and only my not being there is going to prevent it.” Pfc. Kurt Vonnegut seemed to invalidate the latter and validate the former. This spoiled, good-looking, tightly-laced soldier was definitely “there.” He was captured in Germany at its most bombed and strafed, and spent the remainder of the war within torturing distance of the German guards in the Dresden prison camp he would immortalize in print. His comrades died within mere inches of him: 150 killed by Allied bombs on a troop train bearing Vonnegut to prison; upon getting out fourteen were killed by a Russian plane.

From this, Vonnegut could have concluded he was spared by God for great things. But he took from the war only irony and the idea that humans have no preordained destiny. Vonnegut remained a lifelong atheist—not even old age tempted him toward the possibility of a heaven—but he was an odd atheist. He constantly advised those without families to join a church, which would provide them with an extended one—“as essential to humans as food and shelter.” He found Christianity much more “human” than other religions and noted that the Catholic Church provided shelter to Vietnam draft resisters.

What’s striking about Dan Wakefield’s collection of letters written by Vonnegut from 1945 to his death in 2007 is its gentle tone. Most ex-soldiers of the “Good War” came back angry that their efforts to liberate Europe from tyranny brought in a new form of it in the personage of Josef Stalin. Others were irritated to the point of violence by the civilian view that combat was an athletic contest that followed the rules of sportsmanship. But Vonnegut returned a humanist. He not only foreswore killing but hating as well. In a letter to his friend and fellow writer Jerome Klinkowitz, Vonnegut proposed amendments to the U.S. Constitution, not to ban guns or punish war criminals, but instead advocating “that every newborn will be sincerely welcomed, that every young person reaching puberty will be declared an adult, that every citizen will be given worthwhile work to do, and that every citizen will be made to feel that he or she will be sincerely missed when he or she is dead.”

Vonnegut described his religion as “freethinking,” and this led him into all sorts of deviations from secular doctrines. As broached in a 1999 letter to friend Robert Maslansky, he found natural selection “absurd” as the philosophical basis for Nazi atrocities. This teleological socialist found humankind as composed of “warlike primates.” But Vonnegut never completely lost his faith in the human potential for good and wanted put on his tombstone the quote from Nietzsche that “Only a person of deep faith can afford the luxury of skepticism.”

Readers will find these letters invaluable for they show that Vonnegut never settled into an ideological rut. Most of us become more conservative with age but Vonnegut never stopped questioning everyone and everything in the most gentle way possible. “Most people don’t have good gangs, so they are doomed to cowardice,” he wrote to novelist Mary Bancroft in 1972. “The Utopian dreaming I do now has to do with encouraging cheerfulness and bravery for everyone by the formation of good gangs.”

One of Vonnegut’s most touching sentiments comes at the end of a letter to his youngest daughter, Nanette: “P.S. The last time I saw you, you were certainly one of the nicest people I had ever seen. Now I hear that you are learning to dance. That makes you just about perfect.”![]()