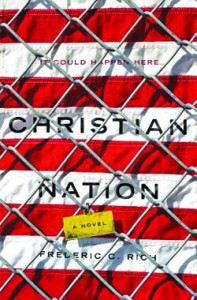

Christian Nation

In 1935 acerbic Minnesota novelist Sinclair Lewis wrote It Can’t Happen Here, a disturbing book about a fascist takeover in the United States.

Fifty years later, Margaret Atwood published The Handmaid’s Tale, another disturbing book, which outlines a future America run by the theocratic forces of the religious right.

These dystopian visions of our country have now been joined by a third, equally disturbing book, Frederic C. Rich’s Christian Nation. Rich’s novel is a retelling of recent history, presenting an intriguing “what if?” It’s a speculative work of fiction in which Barack Obama narrowly loses the 2008 election to the John McCain/Sarah Palin ticket. A few months later, McCain dies of a stroke while on a state visit to Russia. Palin is elevated to chief executive.

Although it quickly becomes obvious that Palin’s in over her head, things change rapidly on July 22, 2012, when coordinated teams of terrorists use missiles to down airliners in seven states. Nearly 7,000 people are killed. Palin declares martial law and delivers a tough-talking speech. A terrified population supports her.

There’s worse to come. Riding a wave of “Teavangelical” support and anti-Muslim hysteria, Palin is reelected in November; reactionary Republicans take control of both chambers of Congress.

But rather than deal with the problem of terrorism, Palin quickly sets about pushing an aggressive social-issues agenda. In short order, federal courts are stripped of their right to even adjudicate church-state cases. Houses of worship are freed to dive head first into partisan politics. States are given the power to ignore the Bill of Rights.

The next president, a Palin advisor named Steve Jordan, ushers in a so-called “New Freedom” program anchored in something called “The Blessing,” a ten-point program that cements the nation’s fate as an officially “Christian nation.” (Point Three of The Blessing is a statement that the United States “recognizes the authority and law of our Lord Jesus Christ,” language that echoes similarly named amendments that were introduced in nineteenth-century America.)

To find out what happens next—and a lot does—you’ll have to read Christian Nation. What makes the book so intriguing is that it’s heavily anchored in real people and real events. Religious right leaders Ralph Reed and Michael Farris

make an appearance, alongside Alabama’s infamous “Ten Commandments Judge” Roy Moore (who ends up with a seat on the U.S. Supreme Court. Yikes!)

What’s more, all the laws and repressive measures Rich introduces in the book have in reality been proposed. As Rich points out, religious right leaders have been saying for a long time what they want to do. No one should be surprised when they try to do it.

For example, proposals that would strip the federal courts of their right to hear certain types of cases (usually church-state related) have been knocking around for years and have been embraced by the religious right. Similarly, a series of harsh anti-gay laws that are imposed on the nation in Rich’s novel may sound fantastic—until one remembers that it wasn’t that long ago that some far-right religious and political leaders proposed quarantines for gays, and even today some states are trying to bar gay people from adopting.

Although told through the eyes of its first-person narrator, a Wall Street attorney named Greg, Christian Nation is as much the story of Sanjay, a young resistance leader who provides much of the story’s intellectual background. It’s through his voice that the reader learns of the “dominionists,” an extreme brand of religious right activists who believe God has given them the task of taking “dominion” over the nation. (This movement is not a fictional creation of Rich’s imagination; such people, also known as Christian Reconstructionists, exist. In fact, they provided much of the philosophical underpinnings of the modern religious right movement.)

If recent experience has taught us anything, it’s that people who are afraid will gladly surrender their liberties, not just for security but for the mere promise of security (unfulfilled, of course). The Americans of Christian Nation, reeling from the smoking ruins and body count of a horrific terrorist attack, are very scared indeed.

In the end, that’s what makes Christian Nation so interesting—and disturbing. It’s that nagging feeling that, as much as Americans love to talk about their liberties, they would trade them away under the right conditions. As my boss, the Rev. Barry W. Lynn, noted in a cover blurb: “No violent revolution, no blood in the streets, is necessary for Americans to lose their freedoms—just a failure to defend the liberties that we often take for granted.”

Rich, a New York City attorney, clearly did his homework for this book. His analysis and understanding of the goals and methods of religious right groups is deep and penetrating. He probably could have written another history of the movement or a jeremiad slamming theocratic groups. Instead, he uses fiction as the vehicle for his message of warning.

It was a smart choice. Read Christian Nation. You’ll walk away convinced that it could, in fact, happen here—and with luck you’ll resolve to make certain that it never does. ![]()