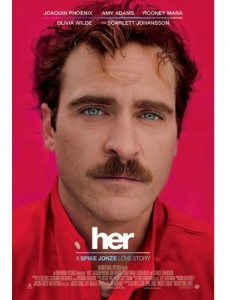

Her Written and directed by Spike Jonze

We’ve all wondered at one point or another—in the aggravating moment when our GPS fails, or when our smartphone’s battery dies—are we becoming overly dependent on technology? Writer-director Spike Jonze takes this question a step further in his futuristic film, Her: As we increasingly rely on our devices, how does it change us emotionally? And as we develop more sophisticated technology and artificial intelligence (AI), could our computers become so intelligent as to have their own emotional needs?

It may sound ridiculous at first, but the world of Her is an entirely plausible imagining of our not-too-distant future. The film is set in a beautiful, sleek megalopolis version of Los Angeles in which citizens wander from place to place, deeply engrossed in their gadgets. We meet the hero, Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix), looking directly into the camera and eloquently expressing his love for someone. Except it turns out he’s actually dictating a letter (hilariously, one from an older woman to her husband) as part of his job as a professional letter-writer. In this particular dot-com enterprise, letter-writers work with customers’ photos and memories to compose their intimate correspondence for them. The “handwritten” letters are printed and sent, complete with the lettering and misspellings characteristic of the supposed authors. As a first glimpse at relationships of the future, it’s endearing to a point, but it’s really kind of weird. (After all, who writes letters anymore?)

Theodore is a lonely and sensitive guy who’s deeply hurt from his drawn-out divorce. He occasionally sees friends but spends most of his time in his apartment, playing video games and finding a pseudo-companion for the night in a phone-sex chat room. Pretty much everything he does involves interaction with his smartphone (which looks like a vintage camera-cigarette case hybrid) and a small earpiece, which follows his voice commands, reads his emails for him, and selects songs to fit his mood. One day Theodore sees a strangely intriguing ad for an artificially intelligent operating system, OS1. “It’s not just an operating system,” the ad beckons, “it’s a consciousness.” He brings it home, answers some awkward setup questions, picks a female voice, and meets his new OS.

Samantha (voiced by Scarlett Johansson) introduces herself in a pleasant, playful, and astonishingly human manner, getting to know Theodore by chatting and organizing his emails. Like a highly advanced version of Apple’s Siri, her intelligence is remarkable: she can scan thousands of pages of data and select relevant information in nanoseconds. Even more remarkable is her capacity for empathy, her ability to understand Theodore’s needs, her desire to understand him entirely and experience the world as he sees it. Samantha wants to know what it’s like to be alive in a room, to have a body. Before long, she’s accompanying him on excursions (via his phone and earpiece) and quickly becomes an essential companion.

That Theodore will fall in love with Samantha seems inevitable, especially considering the completely self-absorbed behavior of a number of the other women in the film (a blind date, his ex-wife, and even his mother). Are their personality defects the result of a pervasive, technology-driven egocentrism? A kind of antisocial behavior encouraged by phony socializing—digital interactions, texting, even having personal letters written by a hired hand—in which people don’t experience fully engaged conversation or the consequence of hurting someone’s feelings in person? Is humanity essentially doomed to a future of technology-addicted people who don’t understand how to handle relationships?

While Her poses these questions seriously, in many ways its imagining of our future society is surprisingly optimistic. The urban environment where Theodore lives is bright, modern, well maintained, and seemingly free of crime, with just enough in the way of the arts (sculptures, street dancers) to make it feel vibrant rather than sterile. Mass transit is clean and comfortable, a train ride to the countryside seems luxurious, and even the crowded L.A. beach is abnormally tidy. Theodore’s extra-urban trips—a picnic on the coast and cabin getaway in a snowy wood—show vast swaths of unspoiled nature, free for human frolicking. This future society seems to have improved the environment, keeping human activity in organized, efficient cities and leaving nature accessible but not exploited. Refreshingly unlike many futuristic movies and TV shows (The Hunger Games, Gattaca, Battlestar Galactica), there’s no dystopian oligarchy, no bleakly ravaged planet, no fear of humanity’s impending evisceration as a result of its own technological hubris. Humans have done a pretty good job in the world of Her. I wouldn’t mind living there myself.

The film’s interior environments and the character’s personal effects add to the positive vibe: Theodore’s cheery office virtually basks in its own vibrant colors—it almost seems like the characters are walking around in Apple’s iOS 7. Meanwhile the furniture and lighting in the office and in Theodore’s apartment have a midcentury modern aesthetic; his old-fashioned glasses and vintage-looking smartphone hearken back to that era as well. Most noticeable is the prevalence of high-waisted pants in menswear, the film’s most obvious signal to the audience that the story takes place in a future decade. And it all makes sense: as technology progresses and old things become obsolete, there’s a counterintuitive response, a sense that the old things are somehow more authentic. That desire for authenticity—in a flawless replica of someone’s handwriting or a manufactured digital “consciousness” bordering on personhood—appears to drive progress in this society. And even when the result is far from authentic, it’s the effort that makes this future world so believable.

Let’s admit it: a person dating an artificial intelligence isn’t that far-fetched. People have been dating online for years now—some people even use smartphone apps to find a hook-up for the night who’s willing and in the vicinity. Granted, these relationships commence with actual people, but they start with digital interactions. If you think about it, dating an artificial intelligence might be preferable from a personal safety standpoint. No need to worry that you’re dating an axe murderer! Even if your AI evolves into a sinister personality, there’s bound to be some kind of return policy. So what’s the risk? Other than the fact that the AI doesn’t have a body, is it really all that different from a long-distance relationship?

In the interest of not giving away too much of the film, I’ll cut to an observational point: romantic relationships are comprised of individuals, and those individuals may grow and their desires may change. This is nothing new. But when it comes to building relationships with personal technology, our addiction to feedback—the call, the text, the “like,” the comment on a status—can really do us in. Computers are built to respond to commands but people aren’t. With devices constantly evolving to make our lives easier, waiting around for a human response may eventually seem like an inferior experience. Will it go so far as to replace people? I doubt it. But dealing with real people might end up taking a lot more patience.

Theodore struggles with this issue, questioning the authenticity of his relationship with Samantha and his feelings about her. He wonders if he’s dating an OS because he can’t handle a “real” relationship. But his insightful friend (who has a close friendship with an OS of her own) counters, “Is it not real?” The level of understanding he has with Samantha is pretty darn convincing. And who are we to say it is or isn’t love, or that their kind of love isn’t “real?”

After all, with or without a body, how close can one person really get to completely understanding another? ![]()