Kurt Vonnegut Survives Humanity

IN HIS EIGHTY-FIVE spins around the sun, Kurt Vonnegut managed to make people smile about the darkest aspects of the human condition. One of his most famous novels, the 1963 campus classic, Cat’s Cradle, deals with the apocalypse, a deadly new weapon, and the invention of a new religion. And it’s funny. That in itself is the marvel of Kurt Vonnegut. He was the kind of guy who, if you were about to walk up the steps to be hung, would stand at the bottom step and say, with an apologetic smile, “You don’t want to be here anyway.”

Vonnegut was the jokester in his family, often needing to deliver excellent performances simply to gain the attention of his more left-brained father and older brother. The trait to please and entertain continued through college at Cornell, but when Vonnegut entered the war, one could say that the wit he’d armed himself with grew teeth. While at Cornell he wrote columns for the school paper laced with humor and satire. Pre-war, Vonnegut could perhaps be likened somewhat to Dick Van Dyke’s multi-talented chimney sweep in Mary Poppins. War’s moody shadow, however, would prove his muse.

Consider, for example, the letter written to his relatives just after his release as a POW in 1945:

I’m told that you were probably never informed that I was anything other than ‘missing in action’… I’ve been a prisoner of war since December 19th, 1944, when our division was cut to ribbons by Hitler’s last desperate thrust through Luxembourg and Belgium.

Vonnegut’s twenty-second year was anything but funny. Six months after walking in on his mother after she had killed herself from an overdose of sleeping pills, Vonnegut was taken prisoner by the Nazis during the Battle of the Bulge. He was placed on a train and packed in like a sardine. He stood for three straight days without food or water. Describing it in the letter to his family, Vonnegut recalled: “We were loaded and locked up, sixty men to each small, unventilated, unheated box car. There were no sanitary accommodations—the floors were covered in fresh cow dung… half slept while the other half stood.” In a different letter, Vonnegut wrote:

I had never been hungry before… you go nuts! But you mustn’t give up. If you give up—if you don’t care, if you lie down and don’t care, your kidneys go bad and you piss blood, and then you can’t get up again and you just wilt away.

His Christmas Eve, 1944, was spent being bombed by the Royal Air Force. “They killed about one-hundred and fifty of us,” Vonnegut wrote. The next day, Christmas, he noted that he “got a little water,” and was finally released from his cow-dung tin can on New Year’s Day.

You’d think it’d get better after that, but no. “The Germans herded us through scalding delousing showers. Many men died from shock in the showers after ten days of starvation, thirst, and exposure. But I didn’t.” (The complete letter is included in Dan Wakefield’s superb 2012 collection, Kurt Vonnegut: Letters.)

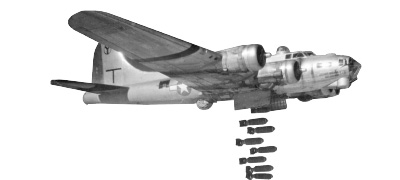

Eventually, Vonnegut was taken to the German city of Dresden, where he was a POW for several months. On February 19, 1945, Vonnegut was inside a basement with his fellow soldiers when British and American airplanes dropped close to 4,000 tons of explosives on Dresden. Vonnegut wrote: “Their combined labors killed 250,000 people in twenty-four hours and destroyed… possibly the world’s most beautiful city. But not me.”

Vonnegut battled depression his entire life. Considering the “but not me” refrain in his letter, one wonders if he took pride in this, or if he simply said it in his now well-known dark-yet-still-here tone. Wakefield, a lifelong friend of Vonnegut’s, smartly alludes to the author’s famous refrain, “so it goes,” which he used in his books whenever death, most often pointless death, came to pass. Wakefield believes the creation of that phrase started with this letter, and I have to agree.

IN THE DAYS that followed the bombing of Dresden, Vonnegut often had to dig holes into the rubble, where he found basements with perfectly preserved dead bodies sitting up, as if nothing ever happened. Days were spent “carrying corpses… women, children, old men. Civilians cursed us and threw rocks as we carried bodies to huge funeral pyres in the city.”

Eventually, Vonnegut arrived back home safely. His uncle allowed him to drive home from Camp Atterbury, about forty miles south of his home in Indianapolis. What does a young man think after being surrounded by bombs, gunfire, and death for such an extended period of time? For all the suffering Vonnegut went through, there was one horrendously tragic story he would never be able to get out of his head.

During his time in Dresden, Vonnegut and the other prisoners of war often went into basements under the rubble. Amidst the suffocated bodies sat shelves of preserved food—apple butter, sausage, carrots. Vonnegut would eventually lose close to forty-five pounds during this period, so it’s safe to say the food he and the other prisoners saw was, from time to time, incredibly tempting despite the risk.

One older soldier, Michael Palaia, gave in to temptation. Before the German soldiers had returned, Palaia grabbed a jar of pickled string beans in advance of the four-mile walk they’d have to make after finishing their work. At the beginning of their imprisonment, everyone, including Vonnegut, had taken a coat from a large pile (coats from the dead, essentially). Palaia, Vonnegut recalled, had chosen a warmer coat that had belonged to a Russian soldier. On the march back into town, a German soldier told Palaia to take off his coat. As he did, there they were—pickled string beans.

The following morning, Palm Sunday, Palaia signed a contract he couldn’t understand. Vonnegut was ordered to accompany him outside. They walked for a while— Palaia, Vonnegut, a Polish soldier, and three other prisoners—with shovels in their hands.

The prisoners were ordered to dig two graves. When they finished, the German guards gave an order to a firing squad. They shot Palaia in the back, right in front of Vonnegut. The firing squad shot him again, along with the Polish soldier, and Vonnegut along with the other prisoners placed their bodies in the graves. The mercilessness of this action, the coldness, remained with Vonnegut until the day he died. On that drive back home with his uncle, he broke down and sobbed while driving. “The sons of bitches!” he repeated, through gritted teeth.

In 1981 Vonnegut published what he called an “autobiographical collage,” and chose the title, Palm Sunday. In a chapter titled, “In the Capital of the World,” he describes a sermon he delivered to a congregation on Palm Sunday in 1980 at St. Clement’s Episcopal Church in New York City. Though not a Christian, Vonnegut still loved and appreciated Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount, in his own way. He spoke this simple yet profound statement: “Being merciful, it seems to me, is the only good idea we have received so far.”

One could say that Vonnegut’s horrific twenty-second year had the most profound effect on his life and career than any other age. Twenty-five years after his war experience, Vonnegut published Slaughterhouse-Five, a novel based on his experiences in Dresden. It took him decades to finally confront that torturous time. The reward was a satirical masterpiece that stands as his greatest achievement. In that novel, a character by the name of Edgar Derby, an older soldier just like Palaia, is shot and killed for stealing a teapot.

If you ever pick up or reread Slaughterhouse-Five—or any of Vonnegut’s other books for that matter—you’ll be reminded that this self-described humanist’s dark humor was organic, and that all he wanted was for people to behave decently and have mercy. ![]()