When Humanism Is Attacked, Have Courage

“To learn who rules over you, simply find out who you are not allowed to criticize.”

—Voltaire

FEAR, THE MOST powerful emotion, is an acid that dissolves trust, eats at human relations, and compromises even the best intentions. Fear conjures up what Harvard biologist and 1999 Humanist of the Year E. O. Wilson calls our “Paleolithic Curse,” the instinctual evolutionary drives for tribalism, violence, and distrust of “the Other.” Born of our protective drive for survival, fear can make even the best of us lash out at perceived enemies.

Humanists rightly fear ISIS, al-Qaeda, and other forms of radical Islam. And on the home front we rightly fear the “American Taliban” of the religious right who murdered abortion provider George Tiller, randomly shot people at the “atheistic” UU church in Asheville, North Carolina, and, most recently, called for making the Bible the state book of Mississippi and introduced laws against blasphemy there.

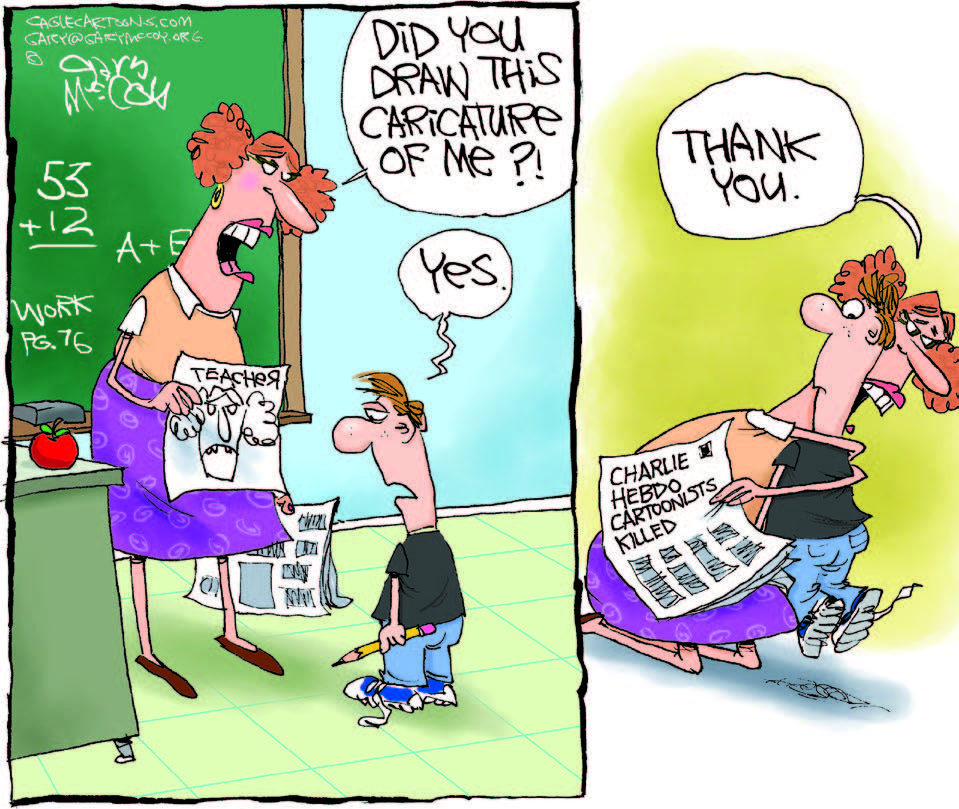

And with the January attacks by Islamic extremists on the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo and a kosher market, our fears remain strong. Catholic League Director Bill Donohue claimed that the magazine’s editor, Stéphane Charbonnier, “didn’t understand the role he played in his [own] tragic death.” From everything that’s been written about Charbonnier, I think he knew full well the risks he took to defend his ideals. Donohue would simply not have us criticize any religion—especially not his own.

I don’t know about you, but I have a visceral reaction to these attacks on Enlightenment values of freedom, reason, and tolerance—the very heart of humanism. At times like this the primordial voice of fear wells up in us and threatens our highest values. Humanists certainly fall along a spectrum of responses to the attacks, ranging from a freethought tradition expressed by Bill Maher, who said that all religions are “stupid and dangerous—and we should insult them,” to our own egalitarian tradition seeking tolerance, education, and compassion in a multicultural society. In truth, most of us are conflicted and drawn to both poles.

Self-censorship has become poisonous to freethought and free speech, and it’s curious how fearful the media have become. The underlying reasons for 9/11, the aforementioned murder of Dr. Tiller, or the massacres in France or Nigeria are variously labeled as poverty, radicalism, political tension, mental illness, and so on. What everyone is afraid to say is that the ultimate cause is a word they dare not speak: religion. No one wants to appear to be religiously intolerant or add fuel to the fire.

These violent radical acts are not an aberration of religion, but the predictable systemic outcome of absolutist Abrahamic religions. When people believe they possess the absolute truth, everyone else is an infidel and every criticism is an attack on the “truth,” which means that everyone else is a danger. Islam in particular is at once the most racially tolerant religion and the most religiously intolerant. For example, in Egypt 88 percent of people believe Muslims who leave their faith should be executed.

When do stereotypes actually become valid descriptions? Islam seems to be the only religion where the political is inseparable from the religious.

Fear is a huge motivator for us to challenge these ideologies, but the danger is that we can then descend to religious bigotry ourselves. It takes real courage to speak out against religion, to stand up for separation of church and state, and to fight for the free mind and an open society against censorship, while at the same time managing to calm our fears and afford each person their dignity. Regardless of others’ beliefs, we should honor their right to freedom of conscience just as we desire this freedom for ourselves.

Fear is a huge motivator for us to challenge these ideologies, but the danger is that we can then descend to religious bigotry ourselves. It takes real courage to speak out against religion, to stand up for separation of church and state, and to fight for the free mind and an open society against censorship, while at the same time managing to calm our fears and afford each person their dignity. Regardless of others’ beliefs, we should honor their right to freedom of conscience just as we desire this freedom for ourselves.

Separating a person’s beliefs from the person is really tough for all of us, but on an individual level, seeking tolerance and understanding is our moral duty. It’s a balancing act with all of our conflicting values and agendas. On a person-to-person basis, common courtesy and good manners discourage the ridiculing of others, but as one person interviewed on TV in France said about the Charlie Hebdo cartoons, “there can be no real satire without blood.”

Increasingly, we find ourselves in this balancing act of deciding when to call out religion as the cause of many of our world’s woes and when to support more kindly tolerance. If you are absolutely cocksure either way, it may be time to look in the mirror. The continued attacks on humanism may help us learn more about ourselves, about our own values, our own ethical responsibilities, and about the inherent complexity and ambiguity of life. A full humanism always begins with courage.

Read all articles in this issue’s Paris Perspectives series.