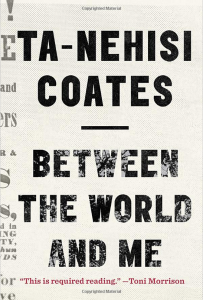

Between the World and Me

BOOK BY TA-NEHISI COATES

SPIEGEL & GRAU; 2015

176 PP.; $24.00

The Black Lives Matter movement confused me at first. I didn’t understand why so many black Americans were so angry. But then I remembered working for a company in the 1980s, where I was confused about why all of the women in my office were angry. I was blind to the sexist actions of our male management because they were never visited upon my male self—I could only see the effects of it on my female coworkers. And now I found myself in a similar situation, only this time it was racism, and the victims were black. So when I saw author Ta-Nehisi Coates being interviewed on television one night, I realized his was a voice I needed to pay attention to.

His book, Between the World and Me, was a revelation. If the rage of black Americans mystifies you, this book will demystify it. Coates distills the anger, frustration, and powerlessness of generations of African Americans into pointed, bold, poetic prose reminiscent of Christopher Hitchens’ writing. I say this in part because Coates is an atheist, a fact that’s overshadowed by the discussion around his racial arguments. However, his “godlessness”—and a profound humanist viewpoint—are deep undercurrents of his book.

For the humanist, Coates’s razor-sharp insights pierce the unspeakable horror called forth by the mindless taking of a human life. Because Coates has no illusion of a life beyond this one, he chooses to focus on the reality of the “body.” Describing his feelings at the church funeral of a college friend shot dead by police, he writes:

Forgiving the killer of Prince Jones would have seemed irrelevant to me. The killer was the direct expression of all his country’s beliefs. …. I believed, and still do, that our bodies are our selves, that my soul is the voltage conducted through neurons and nerves, and that my spirit is my flesh. Prince Jones was a one of one, and they had destroyed his body…When the assembled mourners bowed their heads in prayer, I was divided from them because I believed that the void would not answer back.

Ta-Nehisi Coates

Between the World and Me is composed as a letter to Coates’s teenaged son. As a father, Coates is desperate to create a different, better version of “the talk” that every black parent at one point has with their son or daughter about how to simply survive in America.

All my life I’d heard people tell their black boys and black girls to “be twice as good,” which is to say “accept half as much.” These words would be spoken with a veneer of religious nobility, as though they evidenced some unspoken quality, some undetected courage, when in fact all they evidenced was the gun to our head and the hand in our pocket…It struck me that perhaps the defining feature of being drafted into the black race was the inescapable robbery of time…not measured in lifespans but in moments…It is the raft of second chances for them, and twenty-three hour days for us.

But Coates also carefully tracks his own intellectual and emotional arc from terrified survivor of the violent streets of Baltimore to a man who has clawed his way through a series of worldviews that, although they lent some sense to the jigsaw puzzle of existence, were ultimately incomplete. And along the way, he offers a deconstruction of the history of our modern conception of race itself:

But race is the child of racism, not the father. And the process of naming “the people” has never been a matter of genealogy and physiognomy so much as one of hierarchy. Difference in hue and hair is old. But the belief in the preeminence of hue and hair, the notion that these factors can correctly organize a society and that they signify deeper attributes, which are indelible—this is the new idea at the heart of these new people who have been brought up hopelessly, tragically, deceitfully, to believe that they are white.

Having laid bare the perverse—and pervasive—mythology of whiteness that he describes as “The Dream,” Coates will not settle for a black version of the same illusion.

But the true seismic force of Between the World and Me is Coates’s passionate hammering away on the theme of the black body as the focus of generations of racial violence. This idea may shock the religious, but it should come as no surprise to nonspiritual humanists. We understand that once the physical brain dies, so do we. But there is something poetic and terrifying about the way the destruction of the black body is put into historical context:

Here is what I would like for you to know: In America, it is traditional to destroy the black body—it is heritage. Enslavement was not merely the antiseptic borrowing of labor—it is not so easy to get a human being to commit their body against its own elemental interest. And so enslavement must be casual wrath and random manglings, the gashing of heads and brains blown out over the river as the body seeks to escape. It must be rape so regular as to be industrial. There is no uplifting way to say this. I have no praise anthems, nor old Negro spirituals. The spirit and soul are the body and brain, which are destructible—that is precisely why they are so precious. And the soul did not escape. The spirit did not steal away on gospel wings. The soul was the body that fed the tobacco, and the spirit was the blood that watered the cotton, and these created the fruits of the American garden. And the fruits were secured through the bashing of children with stove wood, through hot iron peeling skin away like husk from corn.

Many Americans express a desire to simply move on from racism as a thing from our past. But if Coates’s book does anything, it shows us just how much our racist past is still very much alive in our present. If the extent of our progress is that whites are terrified to be called racist, and yet remain content to do little to change a still-racist culture, we are hardly ready to “move on.” We may never be able to fully exorcise our more pernicious, subtle, and hidden biases. These are natural to us as human beings. But understanding that our primate brains are disposed toward outgroup prejudice should relieve us from some of the burden of useless guilt at our natural inclination toward biases, allowing us to move beyond them to address the real effects of racial prejudice on our fellow citizens—the things we should feel guilty about.

All of us living today have benefitted in some way from the slave labor that built this nation’s wealth, and therefore all of us have a role to play in healing the wounds of that legacy. Between the World and Me should be required reading for anyone interested in being a part of that healing.