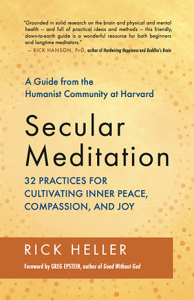

Secular Meditation: 32 Practices for Cultivating Inner Peace, Compassion, and Joy

BOOK BY RICK HELLER

NEW WORLD LIBRARY, 2015

288 PP.; $15.95

The very short review of Rick Heller’s Secular Meditation: If you’re curious about secular meditation and mindfulness, there’s finally a book for you. And it’s a good one.

The somewhat longer review: the book is exactly what it sounds like—a guide to meditation practices, written from an entirely secular viewpoint. And it’s hugely welcome. The vast majority of writing, teaching, and other guidance about meditation come from a religious or supernatural perspective. So when humanists want to pursue these practices, we’re given teachings and techniques we mistrust because they’re founded on supernatural assumptions. We understand that the mind is a product of the brain and the rest of the body, and that the mental or physical practices of meditation might affect how we think and feel—but we have to figure out which of these practices have good research supporting them, and which are nonsense or even dogma. We might even be subjected to teachings that denigrate us, telling us that our supernatural soul is the most important part of our being and our lives are hollow if we don’t believe in it. Even supposedly secular teachings about meditation are often rooted in supernatural ideas about “energy” and whatnot.

I’ve been doing a meditation practice for a couple of years, taught by Kaiser Permanente (my health maintenance organization), but when people who don’t have Kaiser have asked me how to get started with this stuff, I haven’t known where to point them. Now I can point them to Secular Meditation.

The most important thing about this book is that it’s rooted in reality. Heller has been leading meditations for the Humanist Community at Harvard for several years, and the ideas here are based on extensive hands-on experience, feedback from participants in the HCH program, and psychological and neuropsychological research. It’s true that most of the techniques in this book originate from Buddhist and Hindu practices. But they’re backed up by solid evidence about how they affect people, and Heller has adapted these practices in response to this evidence. Heller is good about citing current research and explaining what it does and doesn’t say. And when research is lacking or inconclusive, or he’s basing his ideas on personal experience, he says so.

The author also doesn’t overstate the case. He doesn’t promise that meditation and mindfulness are the answers to all of life’s problems, or even to most of them. Instead, Heller presents these techniques as tools to help reduce suffering and manage everyday life. He acknowledges the value of non-mindfulness types of thinking: planning, anticipation, considering the past and learning from it, daydreaming and spacing out, reflexes, and habits. He presents mindfulness as an addition to these ways of thinking, not an alternative to them. He also offers a variety of techniques, encouraging readers to take what they need and leave the rest. Finally, the book is written in clear, down-to-earth language, almost entirely free of the flowery excesses you see in so much meditation writing. (It does occasionally dip into flowery excesses of the secular, Carl Sagan variety.)

Can you learn how to meditate or practice mindfulness from this book, or from any book? Unfortunately, I don’t think I can answer that since I’ve been meditating and practicing mindfulness for a couple of years, and so I already knew how to do most of what’s presented in the book. I read Secular Meditation to learn some new ways to practice, get new perspectives on practices I’m already doing, and find out if I could recommend it to friends and readers. It’s hard to imagine what reading it cold would be like.

Rick Heller (photo-by Michael Benabib)

I did learn some new techniques though. The instructions were clear and practical, and I was able to apply them without an in-person teacher or group. Heller encourages readers not to rely solely on this book for their practice and to join or start a group if they can. That’s not an option for everyone, though. Some humanists can deal with spiritual-based meditation classes if they’re not too heavy-handed, and can take in the useful bits while screening out the supernatural gunk. But others find the supernatural gunk to be like nails on a chalkboard. I sure do. And while secular meditation groups and teachers do exist, they’re few and far between. My suggestion is: read the book, and if the ideas are useful or intriguing, find whatever in-person support you can. Look for secular groups online; try some spiritual groups and see if you can cope with them; start your own secular group.

I do have a couple of quarrels with Secular Meditation. While Heller insists that meditation and mindfulness aren’t the same as positive thinking—a claim I agree with, by the way—there are times when he slips into that territory. It’s troubling, to say the least, to assert that “happiness is not dependent on external circumstances,” and that you can “[train] the mind to get to a point at which one’s happiness is not dependent on conditions in the world but instead comes from within.” This may be true if you’re relatively comfortable, healthy, and privileged, and are mostly dealing with the frustrations and sorrows of any human life. But what if you’re working two jobs and still can’t make ends meet? What if you can’t find a job at all because you’re transgender and nobody wants to hire you? What if you’re subjected to hateful misogynist harassment and death threats? What if you live in fear of racist police officers? What if you’re dealing with any of the hundreds of forms of systemic oppression? It’s not helpful to be told that your happiness or unhappiness comes from within. It’s victim-blaming bullshit. I’m pretty sure this isn’t what Heller intended, but it’s how it comes across, and it’s not okay.

Now, if you’re dealing with stresses and miseries that bloody well are caused by conditions in the world, meditation and mindfulness might be useful for managing some of it (if you can find time and space to practice it, that is). I have a bunch of my own marginalizations, and these practices can help them feel less overwhelming. And this “conditions in the world” stuff doesn’t permeate the book. I’m just giving you a heads-up that it does show up from time to time. (And I’m giving the author a heads-up for the second edition.)

My other quarrel is with the book’s approach to meditation and mindfulness for people with mental illness, namely that it barely addresses it. A search finds the word “depression” used a total of three times, “mental illness” or “mentally ill” or “mental health” used twice. This is a big omission. About one in five people in the United States experiences mental illness in any given year, and meditation and mindfulness are often touted as tools to manage it. But if people with mental illness want to know more about meditation from a secular, evidence-based perspective, they’re not going to get much help from this book. Some people with mental illness might read it and rule out meditation as a possible tool for self-care, since the topic is barely addressed. Others might try these practices on their own, without consulting their therapist or doctor, and run into real problems. I know it’s impossible for a book to address every possible demographic, but this is a big one, and it’s neglectful to leave us out.

Meditation has been a hugely helpful tool in my own mental health care toolbox. But it can be tricky. If I’m in a bad depressive episode, sitting quietly and letting myself experience the present moment will often make the depression less overwhelming—but it will occasionally trigger a panic attack. If you have a mental illness, mindfulness practices might help, but I strongly urge you to pursue them in consultation with your mental health provider. I wish Heller had urged this as well.

All that being said, this is a valuable book and a fine addition to the secular literature. Humanists have a long tradition of adapting ideas and practices that originated with religion or have been co-opted by it—and meditation and mindfulness are excellent candidates. Secular Meditation is a fine guidebook for throwing out the bathwater and keeping the baby.