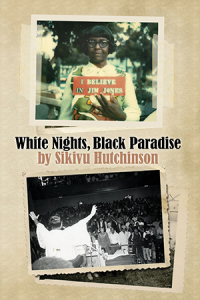

White Nights, Black Paradise

BOOK BY SIKIVU HUTCHINSON

INFIDEL BOOKS, 2015

325 PP., $10.95

Sikivu Hutchinson heads Black Skeptics Los Angeles and is a social justice activist as well as the author of several nonfiction books on race, religion, and gender. Her first novel, White Nights, Black Paradise, is about one of the most disturbing chapters in African-American history, the story of the Peoples Temple and the shocking tragedy in Jonestown, Guyana, where hundreds of people killed themselves while under the influence of the charismatic white preacher Jim Jones. (Three-fourths of them were African American.)

Jones preached a socialist gospel. He bashed capitalism harshly and relentlessly. However, unlike a libertarian socialist or an anarchic-socialist, he didn’t advocate a society without hierarchies. Jones seemed to believe that he had to exert great control over his followers and demand obedience and loyalty from them.

In White Nights, Black Paradise, Jones is portrayed as a complete fraud. He is an atheist who pretends to heal people. At one point he tells his sons, “There is no fucking God,” and even makes similar statements to his congregation. It seems as though everyone in the People’s Temple of the book, including elderly people, curses freely and even during church service. (This reviewer’s never been to such a church. In the 1960s and ’70s one wouldn’t even curse near a church, let alone inside one.)

No one in the novel seems to exhibit what most religious people consider to be “godly” behavior. Church members use drugs, drink alcohol to excess, have premarital or extramarital sex, gossip, betray their friends, physically beat or support the beating of other members, support phony faith healing practices, and so on. (Oddly, the children are bribed with Snickers bars “to get them to report a suspect conversation or random filthy-mouthed epithet.”)

Author Sikivu Hutchinson

How, you might ask, is Jones able to con anyone, then? While preaching a socialist gospel and aiding the poor is necessary for building a church among the poor, it’s hardly sufficient. Any religious movement must at least have the semblance of morality to be taken seriously by its congregants. If nothing else, the open and widespread immoral behavior of the Peoples Temple members should have been the first red flag to alert even the most unreasoning members that something was wrong. Indeed, the world of the Peoples Temple in White Nights, Black Paradise is a world of utter chaos and confusion, and little seems to make sense.

In any case, what Hutchinson offers readers is an excellent blend of social justice commentary and trenchant religious criticism. The United States’ version of democracy is described as a failure, but is socialism a better alternative? Jones’ socialist scheme is certainly not the answer, to say the very least.

One does learn about the influence that organizations can gain by being culturally in tune with African Americans and the poor, and by promoting social justice. Jim Jones welcomes everyone, as Christ supposedly did:

There’s no need for airs and social graces in our house of worship. When we say everybody is welcome we damn well mean it. No qualifiers and no exceptions. Drug addicts and street walkers alike. Hell, our addicts and street walkers are more respectable than most of the so-called County supervisors supposed to be running things here in San Francisco.

Such an attitude gives Jones a tremendous advantage in attracting the poor and downtrodden. (How many churches or humanist groups are so willing to reach out to the “wretched of the earth?” Yet humanist leaders in particular complain that they have difficulty reaching the poor and the disenfranchised.)

The novel raises an important point during a conversation between Jones and the character Ida Lassiter, a black news reporter. Jones says that some “good soldiers for Communism” feel as though “their struggle is the real one and everyone else’s, especially the Negroes’, is counterfeit in some way.”

This has been a major challenge when it comes to uniting diverse groups under the umbrella of social justice. For example, some black males believe that feminism is a white women’s issue, and that LGBT people are “hijacking” the civil rights movement. Most environmentalists believe issues involving climate change should take precedence over all others. As long as people are concerned only with their favorite causes while seeing other social activists as competitors, this will continue to be a challenge.

White Nights, Black Paradise is an exciting novel. In the author’s capable hands, Jim Jones’ charm oozes off the page, and the reader can imagine how a smooth-talking preacher could get the attention of desperate believers seeking social justice. The action moves swiftly and the characters are well fleshed out.

In the author’s note at the end, Hutchinson states that she is “Coming from the vantage point of a black woman writer in a field—Jonestown scholarship and fiction—where African-American feminist analyses are few.” That vantage point is presented admirably and competently in White Nights, Black Paradise.