Confronting Whiteness and the Flint Water Crisis

“We need to teach students to read and write, but we also need to study our cities and our neighborhoods, especially when they are experiencing upheaval.”

—Linda Christenson, “Rethinking Research: Reading and Writing about the Roots of Gentrification,” English Journal (2015)

IT’S TUESDAY, one day after the celebration of Martin Luther King’s birthday, and my students are as animated as I’ve ever seen them. Tonight, Michigan’s Governor Rick Snyder will make his State of the State address and the eyes of the nation will be firmly fixed on Flint. For my students, who live in and around Flint—and who’ve had to avoid drinking the water at their homes and where they attend college due to its high level of lead content—this has become personal, awakening a long fermenting anger about the way their city and community have been treated. Issues of racism, classism, and injustice are bubbling over as several students ask that we focus our first papers on the poisoning of the people in their city.

“This would never happen in a rich suburb,” argues Anita, referencing the 40 percent of Flint residents who live below the poverty line.

“This reminds me of Louisiana after the hurricane. Nobody cared,” argues Nate. “The only reason our Republican governor is even responding to this is because the national news got a hold of it.”

“What makes me mad is the way they make us look—like these poor, incompetent people in Flint who made this happen,” another says. “We didn’t do anything wrong. We were poisoned.”

The discussions continue. Students have spent much of their MLK holiday weekend watching an ugly portrait of their city continue to unfold. Within days of the water controversy becoming national news, Time magazine would depict Flint on its cover with an image of a scarred and desperate African-American child and the headline: “The Poisoning of an American City.”

“It’s not surprising to most folks, because it’s just about black people,” says Amanda with a shrug and a smile. Nearly six in ten residents of Flint are black.

Suddenly the lack of an African-American presence at the Academy Awards isn’t so important. “I think it’s easy to get caught up in the petty issues of celebrities and forget about our own lives, but it can’t happen this time,” argues Tamara. The discussion continues. Questions are asked. Accusations are made. Before the class is over, we’re making plans to examine what the Flint water crisis says about race, power, and society in general. Class members will become investigators, researchers, ethnographers, and storytellers to find their own truth about the water problem and the way it defines them as a people. Before anyone leaves, we’ve discussed the basics of interviewing residents and the general idea of doing ethnographies or descriptively exploring the lives and values of a community.

“The eyes of the nation are on us, and I want to find some answers,” declares another student.

“You were born where you were born and faced the future that you faced because you were black and for no other reason.”

—James Baldwin

IT ALL BEGAN with talk of “fiscal responsibility” for a city that had ostensibly lost its way. Republican Governor Rick Snyder—in the wake of granting huge tax breaks for the wealthy—had chosen to save the state money by changing the way residents of Flint got their water. Rather than continue getting it from Lake Huron, in April of 2014 Flint started getting its water from the Flint River. Snyder would take this action unilaterally and without any input from the people of Flint since, starting in 2011, he had appointed a series of emergency managers to run the financially strapped city. Flint residents started complaining about the smell, taste, and color of the water almost immediately. They were told the Flint River water was fine, however it would later be found (by scientists from Virginia Tech and others who studied its content) to contain dangerously high levels of lead. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, lead exposure can affect almost every organ and system in the body. Children six and under are most at risk and those exposed to lead may experience behavior and learning problems, lower IQ and hyperactivity, slowed growth, and hearing problems.

In his 1988 book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Paulo Freire speaks of liberation through action, of problem posing, and yet few examples can so capture the need to meld academic standards with real life exigencies than a personal crisis. And yet, isn’t this what all writing should be about?

I ask students to read an essay by bell hooks, “Representing Whiteness in the Black Imagination,” that I know will be relevant to our research, especially in terms of the obvious issues of race and power.

In her essay, hooks, a long-respected writer on race, gender, education, and oppression, examines whiteness, blackness, and otherness in our modern world. She further delves into the conundrum of people of color, who are often expected to see their world as devoid of institutional racism while experiencing its ubiquitous presence. “One mark of oppression,” writes hooks, “was that black folks were compelled to assume the mantle of invisibility, to erase all traces of their subjectivity during slavery and the long years of racial apartheid, so they could be better—less threatening servants.” How, I wondered, would my black and white students respond to concerns not only of racism but the failure of most of us to see it pulsating through the most basic problems of the water crisis? Could they respond to the racial element of the problem and to hooks’s argument: “socialized to believe the fantasy, that whiteness represents goodness and all that is benign and nonthreatening, many white people assume that is the way black people conceptualize whiteness”?

“I am invisible, understand, simply because

people refuse to see me.”

—Ralph Ellison

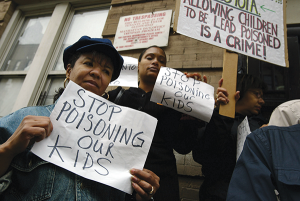

Photo by Spencer Platt

MY STUDENTS ARRIVE early for class, and there’s a contentious edge to many pre-class remarks. While they’re civil, it’s clear that many students—both black and white—have questions and statements to make. It doesn’t take long for a very productive and emotionally charged discussion to begin.

“It’s just wrong to make this about race. I live in Flint and I’m white. I drank the same water,” says Charles, an older student and long-time resident of the city.

“But,” adds Sylvia, an African-American classmate, “that’s what made the article by bell hooks so interesting. In Flint, we are all black. Like Hooks said, we are invisible. This is about seeing a predominately black city as invisible.”

Silence. It’s that watershed moment when the reading has become clear, where a breakthrough is obvious. Marcus, another of the African-American students in the class, responds calmly to Charles. “You’re not black. You’re seeing part of our world, but that’s all. Whiteness is part of everything we do.” Charles nods in acknowledgment, able to see the bigger picture.

In her essay, hooks chronicles the invidious aspects of whiteness and its pervasive presence in the lives of people of color. She mentions the terror experienced by black people as they wend their ways through a society that seems oblivious to the ubiquity of white values and white power in all they do. “The poisoning of our children is a racial issue, because we were invisible to the government—the way we are always invisible to white people,” argues another student, Samantha.

For perhaps the first time, students are transcending the platitudes of fairness and equality that are inexorably fired at them from various forms of media to confront the reality of race and power as it has crystallized before them. “I don’t want to see this as a black or white issue,” says a student named Al, “but living in Flint has made me more conscious of this. I am white but during this crisis I was black. I was ignored by the governor because I too didn’t count.”

“Nah,” another student, Thomas, pushes back. “You can leave Flint, and you’re white again. This is about race, about being black and invisible.”

Of course, such epiphanies are rare in writing classes, so it seems prudent to interrogate the context for these revelations and the reasons why such discussions are important to our highly racial world. First, the water crisis in Flint is multidimensional and part of a bigger problem—one that has been explored by writers for years. In the same way that hooks bemoans the pervasive force of white neglect and paternalism in relation to black people, predominantly black cities, and black symbols, others have suggested that one’s very existence as an empowered person is only possible if it is predicated on the reality of how oppression works. NYU Professor David Kirkland alluded to this in a Huffington Post article published last May titled, “Making Black Lives Matter in the Classrooms: The Power of Teachers to Change the World.” “There are many conversations about race and the various forms of racism happening throughout the United States,” he noted. “Most of them, however, are not happening among white people.” Adds San Francisco State University Professor Jennifer Seibel Trainor, “The student who resists or rejects critical perspectives or who openly expresses racism or sexism in the classroom has, unfortunately, become a familiar figure in the literature on critical pedagogy.”

To explore issues of race and what sociologists call whiteness or otherness is always important for writing classes. In a world where we still must argue that black lives matter, it’s essential that we have safe spheres for examining the presence of institutionalized privilege and how it affects us all. The Flint water crisis is an excellent vehicle for that.

My students, who’ve been thrust into a community catastrophe, are suddenly recognizing the sociological and political underpinnings of their experience. Whiteness is the assumption of rightness and the luxury of ignorance that permeates the white world, despite conspicuous injustice. Many wonder why a contributor to the governor’s political campaign was chosen to lead the special investigation of what the governor knew and if he should be held culpable for the poisoning of a city. Others comment on the presence of the Michigan Militia in Flint. As an all-white conservative group that dedicates itself to gun rights, many of my students wonder how they can help a problem that’s focused on Flint and that overwhelmingly affects people of color.

Freire argues that the basis for a liberated and critical learning context begins with a problem-posing approach—one that challenges students to pose questions about their world and its need for social and political change. When we challenge students to engage in problem posing, we acknowledge the fact that learning is dynamic, political, and empowering. In asking students to deconstruct the political and social realities of the Flint water crisis—a crisis that’s been inflicted upon them as minorities and underrepresented low-income people—students become problem posers and solvers, critical participants answering their own questions rather than passively accepting the answers given to them by those who seem not to care. Problem posing eschews Freire’s banking system, where students are deposited with truth rather than constructing their own.

As Robert Yagelski from SUNY Albany adds, “whatever else it may be (and it is many other things), writing is an ontological act. When we write we enact a sense of ourselves as beings in being the world.”

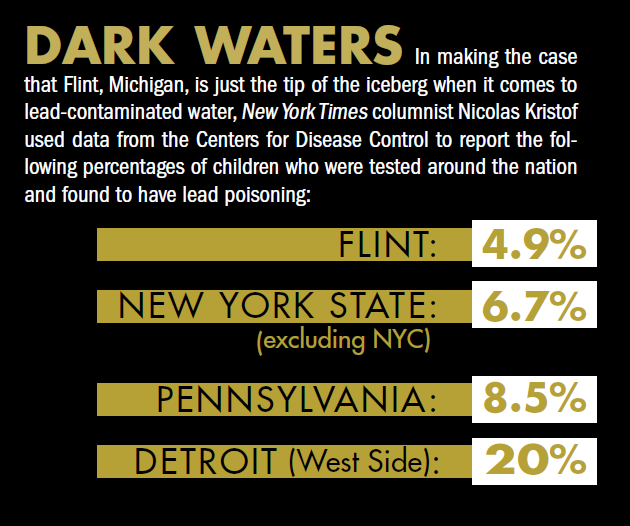

“The continuing poisoning of half a million American children

is tolerated partly because the victims are

low-income children of color.”

—Nicolas Kristof, New York Times, February 7, 2016

AFTER SEVERAL DAYS pouring over articles on the Flint water crisis and interviewing those affected, students are asked to present papers offering a critical perspective. Class member Sandra focuses specifically on hooks’s idea of whiteness and how it can be detected in the crisis. For instance, a longtime political pundit in Michigan, Bill Ballenger, was fired from his job after declaring that the Flint crisis was “vastly overblown.” In quoting him, Sandra suggests that “whiteness is about presenting everything from a white, privileged perspective. So despite the fact that our children are being [endangered] with water, some white [person] can say that the problem isn’t that bad. Obviously, for some, black lives really don’t matter.”

Sandra adds the names of others in power in Michigan who said or suggested that the crisis concerning the water was overblown or exaggerated, and follows with personal commentary about her life as a Flint resident. “I have never felt so hurt by politicians’ words,” she writes, “because I never thought they were aimed at me. But after doing this assignment I realize that I am black, a resident of Flint, and I was the target of these hurtful remarks.”

“The act of writing,” writes Yagelski, “underscores—indeed enacts—the deeper relationship between our consciousness and the world around us.” Clearly, in posing questions about the water crisis and her place in it, Sandra has used writing to expose the whiteness and racism that’s been part of the controversy (erasure of the poor in general being another). More importantly, she’s used both her research and writing to delve into critical questions about her world and her place in it. As a citizen of her city—and as a person of color—asking difficult questions about the politics of poison water, she’s become empowered. “The writer writing is a human being living,” Yagelski affirms. “And the act of writing can give that writer the means to change her life.”

The final project of another of my students, Donovan, revolves around the people in Flint and the real lives that were ignored by the power players and by the media. Donovan’s family was one of many threatened because they refused to pay for the toxic water that was flowing into their homes. “My parents are being harassed for not paying their water bill,” he begins. “They are expected to pay for water that has lead, that could create scars on their faces and cause neurological damage to their kids. This is how valuable lives are in Flint.” As part of his paper, he includes interviews with other residents who’ve been pressured to pay their bills and the strange conundrum the scenario reveals. “If people don’t pay for their water, the city goes further into debt. But the city has been managed by the state since it became financially unstable, so why should the people of Flint suffer?”

The final project of another of my students, Donovan, revolves around the people in Flint and the real lives that were ignored by the power players and by the media. Donovan’s family was one of many threatened because they refused to pay for the toxic water that was flowing into their homes. “My parents are being harassed for not paying their water bill,” he begins. “They are expected to pay for water that has lead, that could create scars on their faces and cause neurological damage to their kids. This is how valuable lives are in Flint.” As part of his paper, he includes interviews with other residents who’ve been pressured to pay their bills and the strange conundrum the scenario reveals. “If people don’t pay for their water, the city goes further into debt. But the city has been managed by the state since it became financially unstable, so why should the people of Flint suffer?”

Donovan considers those who’ve been struggling peacefully to understand the problem while dealing with government officials who seemed apathetic to their plight. He suggests that the bizarre act of asking for payment for toxic water is proof of what hooks calls “absence of recognition” and the contention that whiteness is a failure to see black people as anything more than an abstraction or as a metaphor for problems. “I have never considered this to be personal or racial until now,” he concludes.

Transformative writing comes not from the well-planned, tightly controlled essay but from the conflicts and tensions that flow naturally and urgently from the viscera of the writer. It’s best when it has the smell of the authors’ cultures, the blood of the people who’ve used it as a way to delve into the truths and lies that populate their worlds. In the case of my students—many of whom live in a city of poison water—this has been an opportunity to research and explore, to become problem solvers during a period when they’ve felt both invisible and empowered.

“I never thought of this as a moment to learn about race and myself,” says Marcus as we conclude projects and another discussion. Of course, a class doesn’t have to be propelled into a water crisis to write about transformative topics. As Kirkland reminds us, “teachers are human rights workers, and our classrooms are progressive vineyards thirsty for liberation’s laborers. Classrooms are never neutral sites.” Educators must have the courage to pursue the topics that will help students critique their worlds, leading them to discover more about themselves and become problem solvers while learning about language as a liberating vehicle for truth. We must refuse to shy away from the controversies that touch our students and animate their lives.

Sidebar: Other Students of the Crisis

A team of Virginia Tech undergraduates and graduate students, led by Professor Marc Edwards, were instrumental in forcing officials in Michigan to finally acknowledge dangerous levels of lead in the city of Flint’s water.

A team of Virginia Tech undergraduates and graduate students, led by Professor Marc Edwards, were instrumental in forcing officials in Michigan to finally acknowledge dangerous levels of lead in the city of Flint’s water.

One of the Flint, Michigan, residents hailed as a hero for doggedly bringing up the water issue and for contacting the Virginia Tech researchers to have it tested is a white mother from Flint named LeeAnne Walters. After her children experienced rashes and hair loss after bathing and her three-year-old stopped growing, Walters educated herself on water treatment and research, contacted the EPA, and was introduced to Edwards, whose team of students sent water testing kits to Flint residents and followed up with site visits. Their work confirmed that the chemical composition of the Flint River water made it corrosive and that because pipes weren’t treated with an anti-corrosive agent, lead was leaching into the water people were bathing in, cooking with, and drinking. (The level of lead in Walters’ water was more than twice the level the EPA classifies as hazardous waste.)

Edwards and his team were later sought out by Michigan officials for their expertise in responding to what Governor Rick Snyder eventually deemed a state of emergency. In a New York Times story published February 7, a Flint resident said the Virginia Tech team became the “only people that citizens here trust, and it’s still that way.”

—Humanist staff