3 Meditations on the Death of My Mother

The author

and his mother, Joan,

at her graduation

from the University of

California Santa

Barbara in 1957.

The author

and his mother, Joan,

at her graduation

from the University of

California Santa

Barbara in 1957. I LOVED MY MOTHER. I’m sure you love your mother, too. Joan Adele Rice Naff (1931-2015) would be indignant to find clichés here, so let’s muscle the mush out of the way. She died December 9, 2015, four days after a catastrophic stroke. Waves of grief continue to batter me, yet her death was no tragedy. She lived to eighty-four, and though she had several strokes along the way her personality and especially her sense of humor remained intact to the end. She deserves a eulogy, but this isn’t it. Rather, this represents a humanist’s close-up attempt to make sense of decline and death. To that end, I’ll glimpse her life through my three favorite lenses.

SCIENCE

Joan lived in pretty good health until 1997. By then she’d quit smoking and cut back on drinking. But that year, at sixty-six, she suffered her first stroke. It knocked out her ability to form proper sentences and to read, two things that were absolutely central to her life. I feared she’d end her days in misery. But the brain is the most amazing thing. It has many specialized modules, but unlike, say, the hardware in a smartphone, the brain’s modules are all made of the same stuff, mainly neurons and glia. That allows the brain to recoup after taking a hit. If you were to zap the chips in your phone that process GPS signals, there’s no way it could reorganize and recover the ability to tell where it is. The brain can do that and more. It can generate a mind, and the mind can boot up something we call “will.”

Strict materialists deny the possibility that the will can cause something that wouldn’t otherwise have happened. To be more precise, they view the internal experience of “will” as the phenomenological byproduct of a long chain of causes that, in some sense, goes back to the Big Bang.

I’m no mysterian, but I view will as an authentic, emergent cause, and from that standpoint it’s amazing to see what it can do. Joan summoned hers to make a phenomenal rebound. She not only regained her eloquence but resumed outperforming us all on the Sunday New York Times crossword puzzle. She also regained the ability to read and write.

A second, larger stroke hit in 2010. The neurosurgeon who operated told me that people rarely survive such massive cranial bleeding. I’d like to say that she willed herself to live, but the reason is more prosaic. Her brain, he explained to me, had shrunk a bit in the aftermath of her first stroke, leaving just enough room for blood to pool. All the same, the damage was profound. When we gathered around her in the ICU, Joan was barely present. She couldn’t open her eyes, and when they were opened for her, she couldn’t make sense of the visual field. She could wiggle the toes on her right foot, but her whole left side was unresponsive.

When we spoke to her she answered in short, flat monosyllables. Her consciousness, I thought, had shrunk to a point, like the bright dot that used to appear when you switched off a TV set. My brothers, our dad, Tom, and I feared she would never walk or enjoy life again. The doctors said she suffered from amyloid angiopathy, which means, roughly, that the rubber tubing of her cranial blood vessels had turned to glass. They would surely shatter again. Joan’s life expectancy was down to a year.

Once again, she surprised us. The wonderful staff at Magee Rehabilitation Hospital in Philadelphia taught her how to walk anew, climb stairs, solve puzzles, and make sense of the world around her. Still, Joan’s left arm was unresponsive, and her mind was frequently rumbled by delusions. Ordinarily, we observe or experience consciousness as a smoothly integrated whole. Joan’s now suffered from considerable fragmentation.

They belted her into a wheelchair. It prompted Joan to ask me when she had been taken prisoner by the Army. She remembered her long-dead parents and assumed they were alive. She claimed that she and Tom flew from Philadelphia to California each night to see her father. Later, when that idea lost credibility, she told me her parents had committed suicide. By the time she returned home, she lived a fairly normal life, thanks to the unceasing care my dad and brother provided. She could converse, make acerbic jokes about our dad, and solve the occasional crossword clue. On sunny days she could enjoy walks in the park with Tom.

Come night the terrors would set in. She would look around the bedroom she and my dad shared for more than forty years and fail to recognize it. Her brain would search for memories and only retrieve ones that were way out of date. Considerable remodeling had gone on in both her brain and the bedroom since 1967. The mismatch convinced her that we were about to be discovered in someone else’s home.

The third and final stroke came in the early evening of Saturday, December 5. Tom was helping Joan back to her chair after a bathroom visit. She stopped, looked around the room, and then froze. Her eyes went blank, her mouth still, and her body rigid. Tom yelled for my brother Derek to come help. By the time Derek raced up the stairs, her knees were beginning to give way.

Derek says that as he laid her down on the carpet, her eyes were blank, her face expressionless, but her hand patted him on the rear end. He thinks she was saying goodbye.

Maybe. Consciousness can be dissociated. One of evolution’s good tricks is to double an organ and then let each specialize. This happened with our brains a long time ago. We now actually have two brains functioning together. Occasionally, a young person with severe epilepsy will have a hemisphere removed. The remaining hemisphere develops into a normal brain, giving the person a full range of intellectual and emotional capacities. Sometimes, surgeons cut the corpus callosum, the bridge that connects the hemispheres, to limit the lightning storms of epilepsy. Experiments show that once it’s cut, the two hemispheres operate independently (though the mind fabricates stories to maintain the illusion of unity). Conceivably, then, Joan’s right hemisphere, furthest from the stroke, remained conscious long enough to give Derek a farewell pat.

Maybe. Consciousness can be dissociated. One of evolution’s good tricks is to double an organ and then let each specialize. This happened with our brains a long time ago. We now actually have two brains functioning together. Occasionally, a young person with severe epilepsy will have a hemisphere removed. The remaining hemisphere develops into a normal brain, giving the person a full range of intellectual and emotional capacities. Sometimes, surgeons cut the corpus callosum, the bridge that connects the hemispheres, to limit the lightning storms of epilepsy. Experiments show that once it’s cut, the two hemispheres operate independently (though the mind fabricates stories to maintain the illusion of unity). Conceivably, then, Joan’s right hemisphere, furthest from the stroke, remained conscious long enough to give Derek a farewell pat.

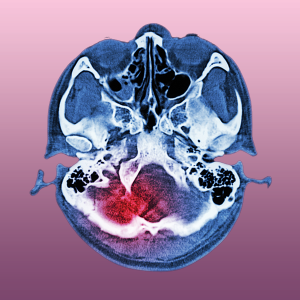

Before long, however, her whole brain was devastated. Her previous hemorrhages had left stagnant pools all over the place, but this new stroke hit like a tsunami. The CAT scan showed white bulges on the right, a dark tide on the left, and an ominous bowing of the midline of her brain. There was no coming back from this one.

RELIGION

A central preoccupation of many religions is to cheat the grim reaper. Joan never flinched at death. Throughout her life, she showed no fear of dying, and when we assembled the family more than a decade ago to have an end-of-life discussion, she was forthright about welcoming it once her ability to maintain meaningful relations with her loved ones eroded. I strongly suspect that letting go of religion had much to do with her courage in facing nonexistence. More on that in a moment.

Joan grew up in a family that fled Kansas and Oklahoma for California, only to find drought there, too. They left the farm behind, and with it regular church attendance. Her parents remained nominally Christian but rarely attended services. One of Joan’s aunts became a fervent Evangelical, but the rest were largely indifferent. Still, the family thought of themselves as Christian. When Joan met Tom in college, she discovered that Christianity comes in many packages.

Tom’s parents were Lebanese immigrants, part of the great wave of Christian emigrants fleeing the Ottoman Empire when the Sultan decided to conscript Christian men into its army. Christianity in Lebanon came in several varieties. Tom’s parents, Faris and Yamna, were Syrian Orthodox, an Arabic spinoff of the Greek Orthodox Church. While in college Joan and Tom casually agreed to let go of religion. It was a fateful decision. When they decided to get married, they found themselves obliged to wed three times: first, before a magistrate, second, in a Protestant ceremony, and third in a Syrian Orthodox ritual.

But with that, religion left their lives and never really entered the home my brothers and I grew up in. Ironically, we never felt more Christian than when our dad taught at the American University in Cairo from 1960-1966. In Egypt, nationality and religion were equally markers of identity, and while we weren’t observant Christians we clearly weren’t Muslims. We celebrated Christmas and Easter, but only with the remnants of their pagan origins—illuminated Christmas trees, the Easter Bunny and egg hunt (fertility symbols, anyone?). We sang Christmas carols. I still do.

Joan drank, smoked, and conversed with men, something few Muslim women would have done. She even danced sometimes, something her Baptist aunt would have condemned. Joan also worked hard, created much, and mentored many. Once we boys were past puberty, she resumed studying literature and earned a master’s in teaching English. Did any of that set her up for the strokes she suffered? Impossible to know. Odds are guideposts, not rail lines.

But to return to the point: observing Joan, and having been a bystander at the deaths of others, I’m convinced that belief in a conditional afterlife adds to the pain and uncertainty of losing a loved one. By contrast, being sure that death is merely the unwinding of your personality into the stardust it came from holds no terrors. There’s no judgment, no fear of waking up in a coffin, no limbo, no finding yourself in “the wrong place.” There’s only the same oblivion you didn’t experience for billions of years before your birth. Nothingness is nothing to fear.

Joan knew this. Well-meaning people, including a chaplain, came by the hospital room and murmured about “going to a better place” or “preparing for the next life,” but that would’ve meant nothing to her. And for my father, my brothers, the grandchildren, and me, it was a comfort to know that once she was gone, what remained of her were the memories, stories, and images we share. Everything of Joan is in our hearts, heads, and hands. The rest is silence.

HUMANISM

Dr. Josh Levine is a compact man with a long, sensitive face, a soft voice, and quick eyes. He gathers information and reaches understanding in one swift, smooth, action. He and a flock of internists, residents, and medical students circulate through the neurointensive ward, pushing laptops on wheeled stands. At each bay, a critically ill or injured patient hovers near death. The flock gathers, listens to the nurse, reads data, and then shares views. Sure, this is big medicine, and yet it’s remarkably humane.

At one stop, a patient begins to thrash and rave. Another lies still and pallid as a corpse. Joan is a middle case. Her chest heaves. Now and then expressions skitter across her face. She frowns and occasionally pouts. But her eyes are shut, and when a doctor gently raises an eyelid and shines a thin flashlight beam into her eye, her pupil fails to react.

The author’s parents, Joan (right) and Tom.

Tom asks if it’s true that her chances of recovery are nil. “A recovery now would be in the category of miraculous,” says Dr. Levine. It’s just the right thing to say to this family. We believe in probabilities, not miracles. “I’d say it’s 99.99 percent likely that she won’t recover. If we remove her from life support, she’ll die.”

That’s important information, but there’s something else I want to know. I try to frame it to invite frankness. “Dr. Levine, if I were to say to you that, based on those CAT scans, there’s no personality or consciousness left in there, would you contest that?”

He pauses, and then lays it bare: “The woman you called your mother is gone,” adding, “It was as quick and gentle an end as any of us could hope for.”

Tears flood my eyes, but I’m glad to know this. How much worse would it be to hear that she’s suffering locked-in syndrome, conscious but cut off from the world?

My brothers Bryan and Derek, Derek’s son Keaton, and our dad gather in a conference room. Linda, a family friend and a doctor, joins us. What will happen, we wonder, if life support is removed? Linda warns that even with consciousness gone, it can be distressing to families. The patient may instinctively gasp and convulse.

Nonetheless, we agree: it’s time to pull the plug. But should we be present? I jump in and say yes, but it’s okay if no one else wants to. As a humanist, I’m certain there’s no one in there suffering. Tom says he wants to be there. Bryan looks anguished, but says he’ll be there, too. Derek says no, he doesn’t want to taint his final memories of Joan but later changes his mind.

My mother declared in her will the desire to be cremated but said nothing more. In life, she had an organ-donation card, and we all know that if she could do some good with her body after death, she would. But how? We consider organ donation, but we’re soon convinced there’s nothing left to give. Who would want an eighty-four-year-old heart whose original owner had a history of drinking scotch and smoking Parliaments? Her eyes, never good, had cataracts up front and macular degeneration at the rear. Even her skin, Linda said, wouldn’t likely do much good. Eighty-four is not the new twenty.

With organ donation out, Tom pushes for donating her body to science. That’s what he wants for his own. In fact, his brain already has a reservation at a research center at the University of Pennsylvania. But Bryan says that having some portion of Joan’s ashes is important to him, and I point out that her stated wish is to be cremated. If those two are compatible, then I’m okay with it. So, what if her body goes to medical students to practice on, followed by cremation and return of whatever is left? That’s quite possible, a social worker tells us. But others let us know that it’s not that simple. For one thing, the remains might be cremated with those of many other donated bodies. For another, it could be years before we get anything back. Bryan and Derek are appalled. In the end we come to a consensus on simple cremation, and with that, my father says, we’re ready to sing from the same page. Our song: a dirge.

With startling celerity, the nurse begins to yank yards of tubes from Joan’s arm. This is ethics in action: killing to be kind, or rather walking that fine legal line that forbids euthanasia but allows the passive wooing of death.

At 2 p.m. on the seventh of December, Dr. Levine’s team begins the final step: removal of the breathing tube. It’s Tom’s eighty-sixth birthday. I stand by him, facing Derek and Bryan on the other side of the gurney. With Derek’s admonition about tainted memories in mind, I look away. But things aren’t going as planned. Joan has clamped her teeth down hard on the tube and isn’t letting go.

Syncretic thoughts race through my mind: Damn! Please, let this be over! And, Good for you, Joan! Do not go gentle into that good night!

Eventually, the team pries open her jaws and slips the tube out. Joan’s heart and lungs put up a ferocious fight. By the most generous calculation, her maximum heart rate was 150 beats per minute, yet her heart pounds at 180 to 205 beats for two days. Throughout, she gulps air like a pearl diver breaking the surface. It’s astonishing and distressing to witness. If I believed her mind or “soul” was experiencing this torture, it would be unbearable.

At last, forty-seven hours and eleven minutes later, her heart lurches, then stops. Joan’s hand is still warm as I grasp it. We all say goodbye, kiss her, and, knowing she’ll soon be cremated, take a clipping of her hair. Though lashed by grief, I’ve never been more grateful to be a humanist.