The Arts for Humanists

OVER THE YEARS my wife and I have been very fortunate to have visited many of the great cities of Europe. One of the things we love best, and that we seek out in our travels, are the great sources of art, music, and architecture in those cities. Of course there are the museums, but they’re all the results of the accumulation of art. If one wants to see and hear and experience art in the places where so much of it was born, and where it first lived, there is but one place to find it. One must visit churches.

I admit that, being an atheist and a humanist, and being just about as fallen a Roman Catholic as one can imagine, going into churches causes me a palpable discomfort. In so many ways, they are disturbing places when one reflects on the suffering and superstition and subjugation that underlie it all. I clearly remember recoiling when a tour guide in St. Petersburg, Russia, told us that we would next be visiting The Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum | Architect: Frank Lloyd Wright

But here’s the thing: for centuries, the seat and the source of all power in Europe was the church. There was no aspect of life that wasn’t dictated by the Holy Roman Church. And this is true in all parts of the world and in other religions. In India, for example, among the desperately impoverished living in squalor are Hindu temples and Muslim mosques that will take your breath away.

And so for many hundreds of years, if one wanted to build a magnificent structure, create a grand painting, or write a symphony, barring independent wealth one had to navigate the hierarchy of religion to gain approval and funds. If you needed money to enable your art, then a painting of Jesus or a nice hymn of praise was often the only option. Beyond that was the ever-present demand to please the ideals and the tastes of the benefactor. I often wonder, as I wander through magnificent holy sites full of art and beauty, just what might have happened had people like Michelangelo and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Fra Angelico and Joseph Haydn been left entirely to their own devices rather than being encumbered by servitude to kings and popes. We will never know.

Today, the churches and cathedrals of the world, despite our resistance to them, represent many of the very highest aspirations and achievements of humankind. I have stood in a crowd and looked up at the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City. I have seen the South Rose Window of Notre Dame in Paris. I have stood before the San Marco Altarpiece in Florence. I have looked up in awe at the ceiling of a Jain Temple in Jabalpur, and the Grand Mosque in Istanbul. I have heard Mozart played on an enormous pipe organ in Salzburg Cathedral. And I have stood and almost wept looking at The Pietá in St. Peter’s in Rome. These structures, and the art which they contain, had one ostensible purpose for those who commissioned them: to offer praise to their god. But there was something else. They were meant to tell the people who entered them just who was boss. They also likely encouraged even the poorest worshipers to empty their pockets. How could one not want to be a part of such magnificence, to have even a tiny sense of ownership?

So where does that leave us humanists, left out in the cold without spires or choirs, pews or altars or holy books? I say it leaves us just where we want to be. It leaves us free to discover great institutions wherever we choose. It leaves us the chance to wonder, to imagine, and to see the world as our cathedral, all art as our art, all works of literature and poetry as our holy books, the great works of the theatre as our passion play, all music as our music. I’ve long said that the truest function of art is that it helps us understand what it means to be a human being in a world of contradiction, suffering, beauty, and turmoil, as well as transcendent joy and amazement at the enormity of it all. As a poet, I have tried both consciously and unconsciously to make sense of it all, to revel in the mystery and adventure of life, even in the face of the mortality we all share. It has made my life very rich. Anyone who creates art as a central essence of their living understands what I mean. But for those who aren’t so inclined, art is still theirs to embrace.

So where does that leave us humanists, left out in the cold without spires or choirs, pews or altars or holy books? I say it leaves us just where we want to be. It leaves us free to discover great institutions wherever we choose. It leaves us the chance to wonder, to imagine, and to see the world as our cathedral, all art as our art, all works of literature and poetry as our holy books, the great works of the theatre as our passion play, all music as our music. I’ve long said that the truest function of art is that it helps us understand what it means to be a human being in a world of contradiction, suffering, beauty, and turmoil, as well as transcendent joy and amazement at the enormity of it all. As a poet, I have tried both consciously and unconsciously to make sense of it all, to revel in the mystery and adventure of life, even in the face of the mortality we all share. It has made my life very rich. Anyone who creates art as a central essence of their living understands what I mean. But for those who aren’t so inclined, art is still theirs to embrace.

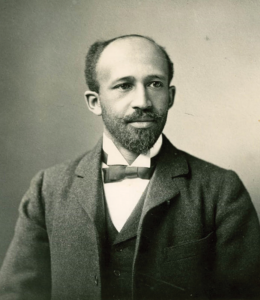

W. E. B. Du Bois

I don’t despair for lack of a Bible. My Bible is called The Complete Works of William Shakespeare and my Koran is the works of the Romantic poets. My court composers are named Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen. The architects of my holy places are Frank Lloyd Wright and Maya Lin. And my cathedrals? Well the names of some of them are the Grand Canyon and Franconia Notch. Let me not forget Niagara Falls and the Great Barrier Reef. And yes, we humanists have our holy figures and saints as well. A few of their names are Charles Darwin, Galileo Galilei, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, W. E. B. Du Bois, Kurt Vonnegut, and Albert Einstein.

So I won’t mourn not having a Mormon Tabernacle Choir. I won’t pity us for not having Westminster Abbey, or (heaven forbid) a Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood. The world of the humanist is too rich to be contained in such modest places as these. My cathedral here in New Hampshire is made of the White Mountains. My church spires are one-hundred-foot-tall Eastern White Pines. The lakes and rivers flow with holy water and the sunset on a day in October is too great for the modest spaces afforded to church windows.

So I won’t mourn not having a Mormon Tabernacle Choir. I won’t pity us for not having Westminster Abbey, or (heaven forbid) a Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood. The world of the humanist is too rich to be contained in such modest places as these. My cathedral here in New Hampshire is made of the White Mountains. My church spires are one-hundred-foot-tall Eastern White Pines. The lakes and rivers flow with holy water and the sunset on a day in October is too great for the modest spaces afforded to church windows.

The experience of art offers us places to find ourselves, to see bits of us in the efforts of people who took the task of living head-on and with all their might. In the creations and the struggles of the artists among us there is enlightenment, there is wisdom, there is the joy of recognition, and there is hope. How sad for those we call devoted, who are taught to believe that all the answers are contained in a single book and that the moments of great praising emanate at scheduled times from a hard seat or on the knees. When we look up in worship, we don’t see a ceiling we can never reach. We see the stars.