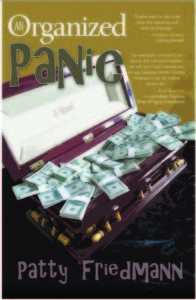

An Organized Panic

BOOK BY PATTY FRIEDMANN

OLD STONE PRESS, 2017

230 PP.; $14.95

It’s a common coming-of-age story for a child to lose their religion as a rebellion against their parents’ strict religious beliefs. But what if that were turned around, and a son gives up the secular humanist beliefs of his family and embraces fundamentalist religious beliefs instead? What if he actually becomes a well-known Christian pastor, businessman, and media figure, thereby sowing the seeds of family discord and dysfunction? How should the secular humanist family deal with that unexpected turn of events?

This is the setting for An Organized Panic, a new novel by the New Orleans writer Patty Friedmann. Ronald Price is the owner of Jesus Cleanup, a cleaning service that, by emphasizing prayer and holiness in cleaning (on ads on late-night TV), has made him a wealthy man. But not wealthy enough to assuage the anger he felt when left out of his father’s will. What wealth Ronald Price does have he attributes to his finding God, and he uses it to live the good Christian life, complete with a large house, a nice family, and an original Thomas Kinkade painting in his bedroom. But it’s not enough, and he wants more.

Specifically, Ronald wants the money he feels is due him from his family, and when his mother, who raised him as a secular humanist, dies, he expects to finally get it and start his own megachurch, where he feels the real money is. But even in leaving him a huge amount in trust, his mother has thwarted this desire by leaving his sister Cesca, a committed secular humanist, in charge of the trust, setting in place the basic plot conflict of the book.

The story is narrated by Cesca, who is mystified throughout by her brother’s religiosity and annoyed by his pomposity and moral arrogance. Cesca herself is a nationally known artist who is extremely rich due to a happy confluence of her family’s money, her own national artistic reputation, and her ex-husband’s financial acumen. She’s determined not to let her brother use his inheritance to build a megachurch, instead trying to keep it in place for the use of his children, in whom she sees much promise. And so the two fight—first at family gatherings and then in court.

Cesca is clearly the heroine. She is witty and free-thinking, sharp and empathetic, with a personality that wins people over to her side and opens them up to her way of thinking—except when it’s her brother. In fact, if there’s a weakness to the book, it’s that Cesca is almost too good, and conversely that Ronald is almost too calculatingly bad.

For Cesca, as it was for her humanist mother, the main puzzle is what drives Ronald’s religiosity. Is it actual belief? Or is it really just about the money that’s rolled in since assuming the role of a believer, and now he’s stuck with the theology for better or worse? There is little doubt she assumes the latter, but the question is never really resolved in the book, although the ending is skillfully developed to allow the reader to draw their own conclusions.

The book is well written; Friedmann has an eye for detail in description and her dialogue moves along smartly and crisply. The plot moves along as well, going from family gatherings to court proceedings in a way that never bogs the reader down. (Perhaps an unrealistic aspect in that court proceedings, in real life, always bog us down. But who wants that in a novel?)

It’s refreshing to see secular humanism so prominently and enthusiastically portrayed in a novel, and used in a way that’s central to its story. Friedmann’s style is fun and engaging, and her characters, while maybe a bit overdrawn, are recognizable and relatable. Humanists will find Cesca’s logic unassailable and will enjoy her irreverence, especially when faced with her brother’s heavy-handed piety. If in the end Ronald’s motivations aren’t clear, maybe that’s because, above all, humanists know that there are no simple answers when it comes to human behavior.