Paranoia and the Pursuit of Happiness

At a cocktail party recently, I met an unemployed mathematician/computer programmer. We talked about real estate, and then she told me how she’d gotten rid of a squirrel that was nesting in her attic, but that after the squirrel was gone she continued hearing noises up there. One night while reading she felt a mysterious pain in her backside. She realized, she said, that it was an invisible ray being beamed at her by an intruder hiding in her attic. She then revealed that she used to work for a high-level government agency, and as a result, she’d been spied upon and, in subtle ways, tortured. In her right eye, the NSA had planted a tiny camera when she stayed overnight in a hospital to treat an eye infection.

I asked her if she’d had her eye examined since then. “Oh, you don’t know?” she said sweetly. “As of 2007, doctors and nurses have been prohibited from talking about, or even revealing, any small metallic objects they might find in your body.”

The mathematician recounted this and much more in a very pleasant matter, always prefacing her revelations with a smile and one of various disclaimers: “I know this sounds crazy;” “you won’t believe this, but,” or “as strange as this may sound.” She was neither hysterical nor caustic. Instead she was bemused and dismayed, like a jaded politician. She seemed to convey that the conspiracies she perceived were as tiresome and inevitable as bad weather.

This encounter unsettled me. Clearly this woman was in pain and clearly, too, she was mentally ill. But others who sound like her—people like my sister-in-law, who believes the 2012 Sandy Hook massacre in Newtown, Connecticut, was arranged by the government—these people are not mentally ill. When my sister-in-law announced her suspicion about Sandy Hook, I looked at her in disbelief. “Really?” I asked, “killing children to promote gun control?”

“Sure,” she said. “Stranger things have happened.”

Have stranger things happened? Or does it simply seem so? If you live long enough, you’ll certainly see and hear many strange and awful things. So I wonder: Are those of us who do not and cannot believe in conspiracies naïve and in denial? Or is something else happening now that allows too many Americans to move beyond skepticism and into the realm of the once-unimaginable?

Sarah, a psychiatrist I know, explained to me that clinical paranoia (a diagnosable mental illness) is distinguished by three traits: it’s a “fixed” (intractable) fear, it’s false, and it’s idiosyncratic. If you’re clinical, nobody’s fear is exactly like yours because you are the target—“they” are out to get you and you alone, for reasons that are specific to your life. The mathematician I met is a classic example. A person with clinical paranoia isn’t simply delusional but also hallucinatory: he or she sees, feels, and hears things that aren’t there. In other words, as a group, people with clinical paranoia have only symptoms in common; they don’t have a shared vision. The new kind of paranoia—I’ll it “cultural paranoia”—is all about sharing. Apparently, there are huge numbers of people who agree with my sister-in-law that the Sandy Hook massacre was born of a conspiracy.

I feel thoroughly alienated from such people. Most of the folks I know believe in their own autonomy and celebrate their freedom daily in various mundane ways, such as driving to the shopping mall without glancing into their rearview mirrors every other minute to make sure they’re not being followed. In short, they haven’t surrendered to the paralyzing miasma of the “Great Unknown,” created by doubt and a pervading sense of powerlessness. But if I admit that it seems these non-paranoid types are diminishing in number here in the USA, am I myself succumbing to a kind of paranoia?

I feel thoroughly alienated from such people. Most of the folks I know believe in their own autonomy and celebrate their freedom daily in various mundane ways, such as driving to the shopping mall without glancing into their rearview mirrors every other minute to make sure they’re not being followed. In short, they haven’t surrendered to the paralyzing miasma of the “Great Unknown,” created by doubt and a pervading sense of powerlessness. But if I admit that it seems these non-paranoid types are diminishing in number here in the USA, am I myself succumbing to a kind of paranoia?

The wife of a friend of mine is a prepper. She spends her free time packing and unpacking and repacking knapsacks designed for survival in the event of a nuclear attack or, more generally, the apocalypse. Packing knapsacks is something of a hobby for preppers (also known as survivalists), who strive to make the most efficient use of such limited storage. They take pleasure, and perhaps delight, in sharing their latest finds: the smallest, most effective water purifier; the highest-powered compact flashlight; and so on. Preppers are usually quiet about their preparations, in part because it’s not wise to broadcast that you’re ready for survival when your neighbors aren’t remotely ready. I recall an episode of the original Twilight Zone that depicted one family retreating to their basement bomb shelter during what seemed to be a real nuclear attack. Their thoroughly unprepared neighbor pounded on the shelter’s locked door and demanded that he be given shelter. The sheltered family explained (through the locked steel door) that there wasn’t enough room or supplies for more people. If this sounds reminiscent of the fable of the grasshopper and the ant, then you’re on the right track. As it turns out, the shut-out neighbor breaks down the shelter door just as he and his neighbors learn that the air raid was a false alarm.

“The United States is an unusually frightened country,” Noam Chomsky said in an oft-quoted interview conducted with a group of students in 2014. “And in such circumstances, people concoct, either for escape or maybe out of relief, fears that terrible things happen.” His observation gestures to childhood, how children tend to conjure the worst things when they lay awake in the dark. Imagining the worst is, at bottom, a kind of control. Since classical psychology characterizes paranoia as a defense against perceived threats, we can better understand why the prepper repacks her knapsack, the militiaman cleans his rifle, and the survivalist catalogues his stores of food.

As a child, I first encountered the word “paranoia” in the 1967 protest song “For What It’s Worth” by Buffalo Springfield:

Paranoia strikes deep

Into your life it will creep

It starts when you’re always afraid

You step out of line, the man come and take you away

Singer Stephen Stills emphasized paranoia as pervasive fear, not unfounded fear. He wasn’t talking about mental illness; he was describing a relatively new state of mind, a cultural phenomenon. This definition became the popular meaning of paranoia as protests for social change incited violent reprisals from state, municipal, and federal law enforcement agencies. The highly secretive, thoroughly paranoid J. Edgar Hoover embodied this violence and enflamed Americans’ mistrust because Hoover was indeed spying on organizations—taping, photographing, blackmailing, and bullying everyone he saw as a threat to American democracy.

Mistrust is rooted in this nation’s founding. In 1788, as politicians wrangled to ratify the US Constitution, Alexander Hamilton complained: “The moment we launch into conjectures about the usurpations of the federal government, we get into an unfathomable abyss, and fairly put ourselves out of the reach of all reasoning.” A year later James Madison observed, “All men having power ought to be distrusted to a certain degree.” Still, Americans have long been characterized as gullible (think of the capitalist’s motto: “There’s a sucker born every minute!”) and in need of prodding by the likes of H.L. Mencken, who observed, “No one in this world, so far as I know—and I have searched the record for years, and employed agents to help me—has ever lost money by underestimating the intelligence of the great masses of the plain people.” At the height of the Cold War, John F. Kennedy warned, “No matter how big the lie; repeat it often enough and the masses will regard it as the truth.”

Historian Richard Hofstadter, writing in Harpers fifty-three years ago, identified what he called a “paranoid style” in politics, epitomized by McCarthyism and characterized by “heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy.” I echo him when he observes, “[This] use of paranoid modes of expression by more or less normal people… makes the phenomenon significant.” But it was nothing new, Hofstadter noted then, tracing the “old and recurrent phenomenon” back century by century and offering a long list of participants, from “the anti-Masonic movement, the nativist and anti-Catholic movement… certain spokesmen of abolitionism who regarded the United States as being in the grip of a slaveholders’ conspiracy… many alarmists about the Mormons,” and on and on. He located paranoid rhetoric mostly in extreme right wingers who felt “America has been largely taken away from them and their kind, though they are determined to try to repossess it and to prevent the final destructive act of subversion.” This certainly captures the tenor of our own times, particularly in the shadow of our recent presidential election.

But the problem with paranoia in America isn’t that there is plenty of cause to mistrust politicians and “the system.” What nation can say it’s free of such mistrust? (We may exclude, for now, Canada.) The problem is that the new paranoia appears pandemic, belonging both to the Right and the Left, and it’s far from clear how we might calm everybody down. Sarah, my psychiatrist friend, theorizes that cultural paranoia has its roots in tribalism: an us-versus-them mentality that helps allay very human fears of isolation and vulnerability. We find comfort in our association with a like-minded cohort of fearful folk and, in fact, we cultivate fears to facilitate this association. “If only we could blame the toaster—something inanimate and unfeeling—instead of blaming each other,” she says, “we might escape harm.” But, she grants, this solution isn’t feasible, since blaming has a palliative effect only when it’s aimed at somebody.

If blame is the primary product of paranoia—somebody has to be at fault for how I feel—then disbelief lies at its seething core. America’s ailment is just this: a bitter incredulity that things aren’t better, fed by a gnawing insistence that life for me should be better: I should have a great job and make more money than my parents made; I should own a new car; I should have a happy marriage and well-adjusted children; I should be debt-free; I should be thinner; I should be prettier; I should have 100,000 followers on Twitter; I should have my own reality TV show; I should be famous! Over 30 percent of American teens (more than 15 million people) believe they’ll be famous one day, while over 30 percent of American adults (more than 80 million people) feel sure they’ll be rich. In the parlance of youngsters, WTF? Americans are carrying historically huge burdens of personal debt (an average of $16K per household of credit card debt alone), in great part due to their expectations of a better life, striving to fulfill all of those should-haves. Marketers have thoroughly exploited these expectations, mostly by selling so-called luxury goods to consumers who, traditionally, could never afford such goods. Glance at the shelves of your local big-box store and you’ll see a large number of products dubbed “premium,” because, as the thinking goes, don’t you deserve the best?

Here’s where things get sticky because Americans’ expectations have been conflated with and confounded by Enlightenment thinking of the most self-serving kind. Start with Denis Diderot, a philosopher of the French Enlightenment who famously wrote, “Liberty is a gift from heaven, and each individual of the same species has the right to enjoy it as soon as he enjoys the use of reason.” Personal liberty and the “natural” rights of the individual are very much central to the thinking of most Americans, nevermind that they’re not aware of these high-flown origins. So too are the perspectives of John Locke and others who trumpeted this revolution in thought, i.e., that the individual is supreme (second only to God) and that all happiness grows from each individual’s fulfillment of himself or herself. That’s how “the pursuit of happiness” got into our Declaration of Independence.

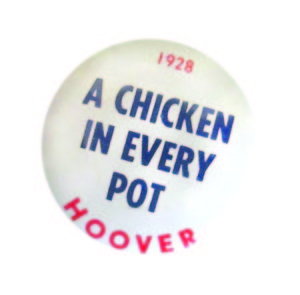

Alas, few Americans read much less study philosophy nowadays. So it’s no wonder that these Enlightenment ideals have been reduced to the most overweening sense of entitlement, to the extent that many Americans think they deserve so much more than they’ve gotten or, dare I say, earned. As an American, I’ve been led to believe that I should be comfortable. Really comfortable. And I’ve tried mightily to meet that expectation. An avalanche of historical circumstances and market forces has impelled me and most Americans towards this mindset. We might locate its start in 1928, when a flier in support of Herbert Hoover’s presidential campaign asserted, “Republican efficiency has filled the workingman’s dinner pail—and his gasoline tank besides—made telephone, radio, and sanitary plumbing standard household equipment. And placed the whole nation in the silk-stocking class.” This was the famous chicken-in-every-pot promise that encouraged Americans to think of the nation’s future not simply in very personal, materialistic terms, but more importantly in luxuriant terms, suggesting that every American should gain entry to the “silk-stocking class.” Is it far-fetched to conclude that Americans are so anxious to “get theirs” that we’ve become the most litigious people in the world?

I remember during the height of the 1979 oil crisis, then-president Jimmy Carter wagging his preacherly finger at us and scolding: “[W]e’ve discovered that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning. We’ve learned that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or purpose.” We spend too much, Carter asserted: we want too much, and we don’t care enough, if at all, about the global consequences of our selfishness. Like most Americans, I didn’t listen to him. Even if we had, what could we have done differently? Nothing in America’s recent history has prepared us to live a frugal, selfless life. I’m embarrassed to tell you how deep in debt I am.

I remember during the height of the 1979 oil crisis, then-president Jimmy Carter wagging his preacherly finger at us and scolding: “[W]e’ve discovered that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning. We’ve learned that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or purpose.” We spend too much, Carter asserted: we want too much, and we don’t care enough, if at all, about the global consequences of our selfishness. Like most Americans, I didn’t listen to him. Even if we had, what could we have done differently? Nothing in America’s recent history has prepared us to live a frugal, selfless life. I’m embarrassed to tell you how deep in debt I am.

It is clear now that many of us won’t be more successful or more comfortable than our parents. Given everything we’ve been told about “the great confident roar of American progress and growth and optimism” (Ronald Reagan), this is frightening news. And so it seems to many Americans that somebody is out to get them, or us, because what’s happening now wasn’t supposed to happen, right? The staggering proliferation of guns in the US is but a symptom of this fear. It looks as though Americans are preparing to arm themselves against an imminent intruder. But from whom do we need protection? “Maybe from zombies,” Chomsky observes. “Whoever it is, we just have to have guns to protect ourselves. That’s not known elsewhere in the world. Maybe in, say, Syria, a country that’s warring you might find something like that. But in a country that’s not only at peace but has an unusual security and a great degree of freedom, that’s quite remarkable.” Perhaps, as Chomsky suggests, our American brand of paranoia is simply a luxury, almost a recreation, which we can indulge only because we have the time and means—the freedom—to do so.

As insurance against a crumbling dream, guns offer a fast and easy kind of consolation that plays very well with American thinking, i.e., that surely something in my life—some unseen advantage, some undiscovered asset—will deliver me from the lousy hand I’ve been dealt. It’s the kind of thinking I’ve seen at flea markets where middle-aged men and women of limited means dump a trunkload of personal belongings on a card table and hope for the best. If you do enough flea markets you’ll learn that everybody’s on the lookout for that one thing: the rare coin or album cover or Confederate uniform button that will make them rich. No other culture in the world is more obsessed by the “one thing” than Americans. It’s Lotto thinking, which is yet another product of that mixed-up Enlightenment mindset, insisting that progress (read: wealth, fame, happiness) is inevitable. Americans spend more than $70 billion a year on lottery games, by the way. That’s about $300 annually for each adult. The election of Donald J. Trump to the presidency was a product of this thinking. By placing a billionaire in the highest seat of power, his supporters believed that some of Trump’s magic—his (alleged) staggering success as a capitalist who knows how to play the system—might rub off on them.

If I were more damaged and more desperate, would I own a gun? My friend Michael said to me recently: “We are all being watched. You may think you own your house and have control over your life, but if the government wants to come and take you away, they will come and take you away.” Michael isn’t among the paranoid. He’s just stating fact: recently, one night, the ATF (the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives) took away one of his neighbors who, apparently, was in possession of illegal weapons. Because my wife and I moved to a farm last year, Michael jokes that we’ll be set when the end comes, referring to fact that I am mostly off the grid and even own a whole-house generator with enough fuel to run it for months. He asks, “Do you feel less scared out there on the farm?” I’ve tried to explain to him that the fear I feel, when I feel it, doesn’t center on the government; it centers on my fellow citizens and what they’re willing to believe.

Trump brilliantly coopted his constituents’ need to believe in him by soothing them with his angry brand of sympathy: his people are the forgotten, the ignored, the overlooked—a characterization that matches their outrage, their thwarted sense of entitlement. He was careful not to call them “poor” or “disadvantaged,” a characterization that would have made them appear weak, even feckless. No, he suggested, these people are not weak. They have shown their strength by waiting for their due. Now it’s time for payback. And so, every one of them raised a defiant fist to the Trump theme song, “We’re Not Gonna Take it!”

The jackpot of such inflationary expectations has been and will continue to be bitter disappointment. That’s why we see so much finger-pointing and so many conspiracy theories—on all sides—and so much cynicism and disgust. Convinced that they’ve been cheated, too many Americans are profoundly unhappy. All their lives, they’ve been told that their prospects are good, in spite of overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Now, it’s getting harder and harder to deny the facts: not every kid can become president; people of color have plenty of reasons to fear for their lives; manufacturing jobs aren’t returning to this nation; technology will eradicate as many jobs as it creates; women are still earning less than men for the same work; and neither you nor I will be rich or famous. Should this realization be cause for despair? Or can we admit that sometimes hard truths are the best truths, that a firm acceptance of reality—however daunting—may give us bedrock on which to build a better world?