From the Slaughter Vonnegut on War and the Book That Made Him Famous

KURT VONNEGUT, age twenty-two, was in a meat locker deep underground with several dozen fellow American prisoners of war, a few guards, and scores of dressed animal cadavers. Above, a beautiful German city was destroyed in a spectacular firestorm caused by explosives and incendiaries dropped from British and American aircraft.

More than seven hundred Royal Air Force planes in two nighttime waves had unloaded some fourteen hundred tons of high-explosive bombs and eleven hundred incendiary devices on Dresden. Fiery, hurricane-force winds roared through buildings, vehicles, and people. Hundreds more US bombers targeted the city’s infrastructure over the next two days.

In between, on February 14, 1945, the captors and their malnourished captives rose from the depths to find that most of the buildings had been leveled and that many thousands of inhabitants had been incinerated.

“If we had gone above to take a look” while the attacks were taking place, Vonnegut later wrote, “we would have been turned into artifacts characteristic of the fire storm: seeming pieces of charred firewood two or three feet long—ridiculously small human beings, or jumbo fried grasshoppers, if you will.”

“But not me,” Private Vonnegut remarked in a letter several weeks after the bombing. He and the others had been spared. However, they had been forced into weeks of gruesome corpse recovery, until finally the bodies—too numerous to collect, let alone properly bury—were burned with flamethrowers.

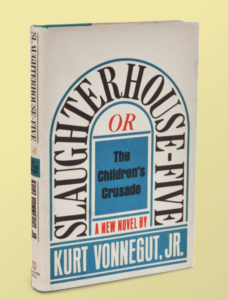

Nearly a quarter century after it happened, Vonnegut used his Dresden experience as the moral center of Slaughterhouse-Five, the novel that brought him wealth and celebrity and his greatest critical acclaim. Within its pages, descriptions of the bombing itself total fewer than a thousand words. But Dresden and its effects can be felt throughout the text.

Vonnegut’s prose ranges from stark anticlimax (“There are almost no characters in this story, and almost no dramatic confrontations, because most of the people in it are so sick and so much the listless playthings of enormous forces”) to low comedy (“A salmon egg flew out of his mouth and landed in Maggie’s cleavage”).

Vonnegut’s prose ranges from stark anticlimax (“There are almost no characters in this story, and almost no dramatic confrontations, because most of the people in it are so sick and so much the listless playthings of enormous forces”) to low comedy (“A salmon egg flew out of his mouth and landed in Maggie’s cleavage”).

There are several of Vonnegut’s best-known characters: ineffectual infantryman Billy Pilgrim; blue-movie star Montana Wildhack; doomed patriot Edgar Derby; and hack science-fiction author Kilgore Trout. Vonnegut himself makes a few appearances. Among the major figures are the Tralfamadorians, little green toilet-plunger-shaped aliens from a far-off galaxy whose concept of a timeless universe becomes Billy’s message to the world. They are absurdist relief, but becoming “unstuck in time” is how Billy deals with the shock of war and his fear of death.

First serialized in the radical magazine Ramparts, the book was published fifty years ago—on March 31, 1969. By then, the United States had already lost well over thirty thousand soldiers in Vietnam and was being wracked by protests. Slaughterhouse-Five found an enthusiastic audience. It was on bestseller lists for months, peaking at number four. It was a National Book Award finalist and was nominated for Hugo and Nebula awards, high honors in science-fiction publishing.

Today it frequently appears on lists of the twentieth century’s best novels. And it retains the ability to shock delicate sensibilities: It was among the decade’s fifty most challenged/banned books as recently as 2000-2009, according to the American Library Association.

Would-be censors misinterpret and mistrust Vonnegut’s message, failing to learn the lesson that suppressing ideas and questions about human conflict and religion and our place in the universe is dangerous.

Vonnegut had been an increasingly successful although not world-famous writer. Slaughterhouse-Five boosted his burgeoning career on the college lecture circuit, and for decades he remained a favorite interview subject in print and on TV.

But even after he’d had a few years to contemplate the money and fame that followed Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut said the experience that inspired it had not changed his life or his outlook. “The importance of Dresden in my life has been considerably exaggerated because my book about it became a bestseller,” he told Playboy in 1973. “Dresden was astonishing, but experiences can be astonishing without changing you.”

By the time Vonnegut was captured in the Battle of the Bulge, he had sustained a personal blow that had changed him. On Mother’s Day 1944, while he was home shortly before his unit headed overseas, his mother deliberately overdosed on sleeping pills. Only nine months after her suicide, Kurt Vonnegut was living underground while Dresden was dying above. For the rest of his life, he wondered whether his mother’s fate would be his. (He did attempt suicide in 1985.)

In 1958 another calamity occurred, when his sister died of cancer just thirty-six hours after her husband was killed in a train wreck, leaving Vonnegut and his wife, Jane, to raise three more children in addition to three of their own. He fought off depression even when his writing career soared.

Eventually, it did soar. Along with it came duties and benefits for Vonnegut such as serving as honorary president of the American Humanist Association for the last fifteen years of his life—which ended in April 2007 due to a fall down the steps outside his Manhattan home.

He was a Hoosier born on Armistice Day, 1922, into a clan of freethinking German architects and hardware store owners. He was a proud soldier who grew to despise his country’s military aims. He became one of the most popular writers in America, and his status as a literary icon remains firm today.

He owes so much of it to Slaughterhouse-Five.

Justifiable Homicide?

Vonnegut’s relationship with what he called “the Dresden catastrophe” was complicated. He said to an audience in 1990, “Should Dresden have been firebombed? No.” At other times he claimed no tears should be shed over the city’s fate, that it was just one of countless examples of humankind’s self-destructiveness, and that “even Germans seem to think it is not worth mentioning anymore.”

Yet Dresden and the global conflict surrounding it affected how Vonnegut felt about his government even though he believed, as he told literary critic Robert Scholes, that “World War II was a good one.”

First, there was uncertainty about the need to level a cultural center that many contend was not a suitable military target. Dresden, sometimes called “Florence on the Elbe,” was renowned for its baroque architecture and world-class museums. It also was the site of a rail hub and more than a hundred factories, some of which produced poison gas and other materials of warfare.

Dresden was one of Germany’s last significant centers of industry and transportation. Still, by 1945 the nation had been crippled, Hitler was hiding in a bunker, Russian troops were advancing from the east, and Vonnegut felt Dresden was “about as sinister as a wedding cake.”

The inner part of the city was virtually wiped out in the mid-February air raids. Most of the roughly 25,000 civilians who were killed—that death toll is the generally accepted estimate now, although Vonnegut relied on an earlier, since discredited, figure of 135,000—were women and children, or males too young or too old for military service.

You can hear the failed attempt at resolution in a quote attributed to Vonnegut in 1971: “How the hell do I feel about burning down that city? I don’t know. The burning of the cities was in response to the savagery of the Nazis, and fair really was fair, except that it gets confusing when you see the victims. …How do you balance off Dresden against Auschwitz? Do you balance it off; or is it all so absurd that it’s silly to talk about?”

Staunch advocates of strategic aerial bombing will disagree, but can “fair really was fair” even be considered a possibility if, in both Dresden and Auschwitz, many innocents were killed? Does the concept of fairness indeed get confusing when you see the victims—or should seeing a city full of dead noncombatants actually clarify one’s moral judgment?

By the time he volunteered to serve in January 1943, Vonnegut seemed to have overcome the isolationist views he’d held even months after the United States entered the war. His willingness to enlist might have been stirred by the possibility of adventure and by his failing grades at Cornell University, but there was a mission too: what he called “near-Holy motives” in trying to defeat the Nazis and Japan, the nation that had bombed Pearl Harbor.

Even many humanists who concur with those motives, however, find fault with certain actions taken by the Allies.

“It makes more poignant the fact that, in the course of fighting a just and justified war, we did things that are deeply questionable, deliberately choosing civilians as a target of a sustained attack,” philosopher A. C. Grayling, a vice president of what then was called the British Humanist Association, said in 2008. Vonnegut’s fellow Dresden survivor and author Victor Gregg, another Brit, explicitly called the Allied bombing of that city “a war crime at the highest level.”

The United States’ role in the massacre, although not as significant as England’s, contributed to Vonnegut’s growing displeasure with his country’s leadership. Dresden “was a British atrocity, not ours,” he wrote, but leveling the city was “pure nonsense, pointless destruction.” Before Dresden, “American civilians and ground troops didn’t know that American bombers were engaged in saturation bombing. It was kept a secret until very close to the end of the war.”

The monumental triumph over the Axis powers overwhelmed the queasiness that some Americans might have felt about how victory had been achieved, and increasingly horrific revelations about the concentration camps helped further dampen misgivings about the more problematic Allied tactics. And debate about the use of atomic weapons overshadowed analysis of massive but relatively conventional bombing raids.

Sheer revenge, then as now, can seem reasonable to the victors. It can be cathartic. Dresden’s firebombing “was a tower of smoke and flame to commemorate the rage and heartbreak of so many who had had their lives warped or ruined by the indescribable greed and vanity and cruelty of Germany,” Vonnegut told an audience at the National Air and Space Museum in May 1990.

Noting that “two more such towers would be built by Americans alone in Japan,” referring to the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, Vonnegut admitted that at the time he “regarded those twin towers as works of art. Beautiful!”

“That was how crazy I had become,” he said. “That is how crazy we had all become.

Poo-tee-weet?

In Slaughterhouse-Five Vonnegut does not spin tales of adventure. He does not try to justify World War II or weep over concentration camps and Pearl Harbor or condemn evil Nazis or praise heroic Allies.

Instead, we are told about hungry and sick prisoners, and a good man who survives the firestorm but is shot to death for stealing a teapot. We get plot summaries of books by an obscure science fiction writer. We get ridiculous-looking extraterrestrials.

Throughout the novel, Vonnegut’s famous detached refrain, “So it goes,” follows whenever death is mentioned, whether of an individual or on a mass scale. Another recurring phrase, after a massacre, is the enigmatic birdsong “Poo-tee-weet?” One response is resignation, the other bewilderment.

They are humanistic responses because the novel leaves no room for help from God—or for that matter from patriotic fervor or cold scientific progress. Rather than lose himself and his readers in existential dread, though, Vonnegut builds upon the elements of fantasy he explored in two of his previous novels, The Sirens of Titan and Cat’s Cradle. He indulges his absurdist streak, leavening his moralizing with ludicrous science fiction that conveys a message or two along with comic relief.

Slaughterhouse-Five protagonist Billy Pilgrim is “unstuck in time,” having been abducted by the travelers from Tralfamadore who can see in four dimensions. These aliens have taught Billy how to perceive time as they do, to “look at all the different moments just the way [humans] can look at a stretch of the Rocky Mountains.”

An example of their philosophy: “Well, here we are, Mr. Pilgrim, trapped in the amber of this moment. There is no why.”

Death is not final because, to a Tralfamadorian, a dead person “is just fine in plenty of other moments.” So, when Tralfamadorians or Billy or the author/narrator respond to death with “So it goes,” that phrase seems a little less glum than it might.

Billy repeatedly jumps through time and space, finding himself back in Dresden, in a Vermont hospital, in a doctor’s waiting room at the age of sixteen, at his wife’s funeral in Ilium, New York, with porn actress Montana Wildhack in an alien zoo, or in a Chicago ballpark telling tens of thousands of people about Tralfamadore on the night of his death.

Billy’s fantastic flights read like dreams and hallucinations caused by wartime trauma—what we now would identify as post-traumatic stress disorder. Slaughterhouse-Five is “not about time travel and flying saucers,” William Deresiewicz wrote in The Nation, “it’s about PTSD.”

On the battlefield Billy is utterly useless, finding “no important differences…between walking and standing still.” Thanks to the Tralfamadorians, however, his memory and imagination free him from the horrors he’s witnessed—and from his fear of death—while they also reinforce his belief that he has no control over what happens to him.

Children’s Crusade

Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut’s sixth novel, wasn’t the first published piece he wrote about Dresden. It’s the flowering of seeds he’d been planting for more than twenty years.

Most of the earlier attempts were short stories Vonnegut submitted to general-interest weekly magazines that were popular after the war. He made enough money selling to the “slicks” that he quit his job as a General Electric publicist and lived fairly well on his writing income until the nation’s attention and advertising dollars switched to television.

Avoiding combat thrillers, Vonnegut produced domestic dramas, some science fiction (“Harrison Bergeron” appeared in many anthologies), and occasional forays into army life reflecting his own background and observations. Much of it was workmanlike material, a long way from the more vivid perspectives on war that would come later.

Vonnegut’s essay “Wailing Shall Be in All Streets,” written after the war while he attended classes at the University of Chicago (but unpublished until 2008), is a heartfelt recording of his growing disgust with wildly imprecise air attacks. Maintaining that US participation in the war was well-reasoned, he directs outrage toward the specific types of airborne acts he witnessed.

“I stand convinced that the brand of justice in which we dealt, wholesale bombings of civilian populations, was blasphemous,” he wrote. “That the enemy did it first has nothing to do with the moral problem.”

Putting his thoughts into sellable fiction proved more difficult than Vonnegut expected. Between the short stories and Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut worked Dresden into two of his 1960s novels. These passages are more focused and personal than his short fiction of that time.

First came a brief but telling mention in the 1965 novel God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater. The title character is on a bus approaching Indianapolis when he has a vision “that the entire city was being consumed by a fire-storm.” He remembers reading about such a thing happening in Dresden. He cannot shake the vision.

In the next chapter, he awakens on the rim of an outdoor fountain to a bird singing “Poo-tee-weet?” That happens to be the last word of Slaughterhouse-Five.

Vonnegut himself had left his hometown of Indianapolis after World War II, moving to Chicago, then Schenectady, New York, then Cape Cod. Visions of a firestorm were consuming him too.

One year after God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, Vonnegut expanded upon the sentiments of his “Wailing” essay in an introduction he wrote for a new edition of his 1961 novel, Mother Night. The book’s plot does not involve Dresden, but Vonnegut’s introduction is his first widely published description of what happened there. It is unsentimental, containing graphic images like the “jumbo fried grasshoppers.”

And Vonnegut, the German descendant, offers a startling observation about evil’s insidious nature: “If I’d been born in Germany, I suppose I would have been a Nazi, bopping Jews and gypsies and Poles around, leaving boots sticking out of snowstorms, warming myself with my secretly virtuous insides. So it goes.”

Vonnegut had gotten much closer to the candidly bleak tone he needed. He’d even found his signature catch phrase.

The type of characters and situations he required to write a book about Dresden, however, were eluding him. He took side trips to Iowa City, where he taught writing courses for two years, and to Dresden, which he and his wartime buddy and fellow firebombing survivor Bernard V. O’Hare visited on a Guggenheim grant that had been awarded to the author.

As told in Slaughterhouse-Five’s autobiographical opening chapter, Vonnegut was shamed into a eureka moment back in Bernard and Mary O’Hare’s kitchen in Pennsylvania. Mary had left Vonnegut and her husband alone to talk. Vonnegut’s youngest daughter and the O’Hare children were playing upstairs. The men, though, were failing again in their attempt to come up with suitable war stories. Then Mary spoke up:

“You were just babies then!” she said.

“What?” I said.

“You were just babies in the war — like the ones upstairs!”

I nodded that this was true. We had been foolish virgins in the war, right at the end of childhood.

“But you’re not going to write it that way, are you.” This wasn’t a question. It was an accusation.

“I — I don’t know,” I said.

“Well I know,” she said. “You’ll pretend you were men instead of babies, and you’ll be portrayed in the movies by Frank Sinatra and John Wayne or some of those other glamorous, war-loving, dirty old men. And war will look just wonderful, so we’ll have a lot more of them. And they’ll be fought by babies like the babies upstairs.”

So Vonnegut promised that, if he managed to actually finish the book, “there won’t be a part for Frank Sinatra or John Wayne. I tell you what…I’ll call it ‘The Children’s Crusade.’” (He did use that phrase as part of the book’s lengthy subtitle: or The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death.)

To properly represent his experiences in the war, Vonnegut realized, he had to forget about portraying soldiers as something other than hapless victims of circumstance. Some of the soldiers he portrayed were based on real people whose service ended tragically.

Dresden in 1945 (Images via WikiCommons)

Dresden in 1945 (Images via WikiCommons)

Billy Pilgrim is an imaginative extension of Rochester, New York, native Edward R. “Joe” Crone Jr., who survived Dresden but died “on a hospital cart of starvation and despair” two months later. “Joe was deeply religious and kind and childlike,” Vonnegut told Crone’s hometown newspaper in 1995. “The war was utterly incomprehensible to him, as it should have been.”

Poor Edgar Derby, who also makes it through the firestorm but is shot to death for stealing a teapot, is modeled after American POW Michael Palaia. Vonnegut and three fellow soldiers had to dig a grave for Palaia, who was executed for stealing a jar of pickled string beans from a basement. Derby’s death is a Tralfamadorian anticlimax, telegraphed from the novel’s first paragraph.

Beyond the essay-like first chapter, Vonnegut himself makes a few brief appearances in Slaughterhouse-Five. He points out his presence when describing, for instance, a procession of prisoners being loaded into boxcars or arriving in Dresden (“the loveliest city that most of the Americans had ever seen”). He’s one of the men suffering ingloriously in a latrine, sickened by a feast that had been prepared for them by English prisoners. “That was I. That was me,” Vonnegut writes. “That was the author of this book.”

Vonnegut includes a portion of himself and what he feared about himself—the struggling, untalented writer—in his most famous character. The impoverished, obscure, and prolific Kilgore Trout had debuted in God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater. He has a bigger role in Slaughterhouse-Five’s follow-up, Breakfast of Champions, and appears in three more Vonnegut novels after that.

These appearances throughout several books are accompanied by roughly forty Vonnegutian parables in the form of synopses of tales written by Trout. Disheveled and cranky, Trout often comes off as a grouchy lunatic, but the story summaries reveal his insights into the perilous but salvageable existence of humans on Earth.

Two such summaries in Slaughterhouse-Five show the affinity that Vonnegut, a self-described “Christ-worshiping agnostic,” had for a merciful, loving Jesus. One of Trout’s books is about how a space alien rewrites the “slipshod storytelling in the New Testament” so that its moral is clearer. In Trout’s tale, Jesus is a nobody who is adopted by God at the last moment and saved from crucifixion. Another Trout book features twelve-year-old Jesus learning carpentry from his father and building “a cross to be used in the execution of a rabble-rouser.”

Those reimaginings of the Jesus story, along with the inclusion of salty language commonly used by American soldiers and civilians every day, are what usually get the novel in trouble with alarmed parents and education officials.

In 1973 a North Dakota school board ordered thirty-two copies of Slaughterhouse-Five to be burned because of objectionable language and sexual situations. In 2011, following a complaint from a college professor, the board of a Missouri high school first banned the book and later placed its copies in a secure library location where they could be checked out—by parents. The Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library in Indianapolis sent a free copy of the novel to any student from that school who requested one.

Slaughterhouse-Five is bound to be challenged again. Its would-be censors misinterpret and mistrust Vonnegut’s message, failing to learn the lesson that suppressing ideas and questions about human conflict and religion and our place in the universe is dangerous.

Vonnegut himself found no lessons in what he called “the Dresden atrocity.” He said he “learned only that people can become so enraged in war that they will burn great cities to the ground, and slay the inhabitants thereof. That was nothing new.”

As a military enterprise, he said at the National Air and Space Museum in 1990, the attack on Dresden was meaningless. It had, he noted, only one benefactor:

Not one Allied soldier was able to advance as much as an inch because of the firebombing of Dresden. Not one prisoner of the Nazis got out of prison a microsecond earlier. Only one person on earth clearly benefited, and I am that person. I got about five dollars for each corpse, counting my fee tonight.