Learning Right from Wrong: How to Teach the Bible in Public Schools

“Exposure to the Bible has an almost magical influence against crime and the moral/ethical slide of our youth and our nation,” wrote Dr. Robert L. Simonds in a 1996 article published by the Institute for Creation Research and titled, “Teaching the Bible in Public Schools?” Simonds answered his question with a definitive yes, but the Bible continues to be used to justify violence towards non-Christians, LGBTQ people, and women. Like others who fight to include the Bible in public schools, Simonds praises its importance in literature, art, history, and culture. Sure, the Bible is an influential book—technically a series of books—that can be useful “when presented objectively as a part of a secular program of education,” according to the Supreme Court.

While it’s constitutional for public schools to teach children about religion, it’s unconstitutional to promote particular or sectarian religious beliefs in public schools. Courses that only teach the Bible, without inclusion of other religious texts or philosophies, provide a very limited perspective of the world and its people. (On January 28, 2019, the Welsh government decided to add humanism to religious education curriculum, and others in the UK are pushing for similar additions.) And there are hundreds of different English translations of the Bible, proving that people have always struggled with how literal the text should be understood.

Last year a wave of bills were introduced in state legislatures that would’ve allowed or required schools to offer elective courses about the Bible—if they had passed. The ACLU was unable to stop Kentucky House Bill 128, which allowed public schools to offer Bible literacy classes as an elective, but have been closely monitoring schools after their investigation found several teachers were using Sunday school materials and making students memorize verses. The legislation in multiple states directly quoted the Project Blitz handbook developed by the Congressional Prayer Caucus Foundation (CPCF), a hyper-conservative group focused on promoting “traditional Judeo-Christian religious values and beliefs in the public square.” CPCF states that the purpose of a Bible studies course is to:

a) Teach students knowledge of biblical content, characters, poetry, and narratives that are prerequisites to understanding contemporary society and culture, including literature, art, music, mores, oratory, and public policy;

b) Familiarize students with, as applicable: (i) the contents of the Old Testament (Hebrew scriptures) or New Testament; (ii) the history of the Old or New Testament; (iii) the literary style and structure of the Old or New Testament; and (iv) the influence of the Old or New Testament on law, history, government, literature, art, music, customs, morals, values, and culture.

Here are the Bible study bills introduced so far in 2019:

Alabama Senate Bill 14 is based on the Kentucky law and would allow the Bible to be taught as an elective for grades six through twelve. The bill would also “allow public schools to display artifacts, monuments, symbols, and texts related to the study of the Bible if displaying these items is appropriate to the overall educational purpose of the course.” Senator Tim Melson, who pre-filed the bill in early February, told an ABC affiliate that he did so because teachers in his district want to teach the Bible but don’t feel comfortable doing so without it being codified in the law. Supporting the bill is the Alabama Citizens Action Program, an organization whose website purports that “an ethical, moral, and responsible lifestyle based on biblical standards is an attainable goal that will benefit the entire state.” In lauding SB-14, ALCAP’s executive director noted: “In the early 60s, we took Bible reading and prayer out of schools and I think we see the result of that in the increase in violence and other problems within the schools.”

Florida House Bill 195 would require public schools to offer courses relating to “religion, Hebrew scriptures, and the Bible” in a secular program taught objectively. As included in the Project Blitz handbook, the bill states that any course may not “endorse, favor, or promote or disfavor or show hostility toward a particular religion, religious perspective, or nonreligious faith.” It’s difficult to trust the courses will be objective when the bill’s author, Representative Kimberly Daniels, has an unsettling history with religion, once calling herself the “demon buster.”

Indiana Senate Bill 373 would allow schools to offer an elective course surveying religions of the world but only require that the curriculum include “the study of the Bible.” The bill also includes clear instructions for the placement of posters that read “In God We Trust” in schools; the addition of “various theories concerning the origin of life, including creation science;” and permission for schools to “award academic credit to a student who attends religious instruction” if the class uses secular criteria. This could be an interesting comparative religion opportunity if handled legally, with the Establishment Clause in mind.

Missouri House Bill 267 allows a school district to offer an elective social studies unit on the Hebrew scriptures, the Old Testament, or the New Testament, but doesn’t mention any other religious text. The purpose of the course is to emphasize the history, literary style, and influence of the Bible “on law, history, government, literature, art, music, customs, morals, values, and culture.” In other words, the course is meant to teach how important the Bible is to every aspect of life, which could easily resemble preaching.

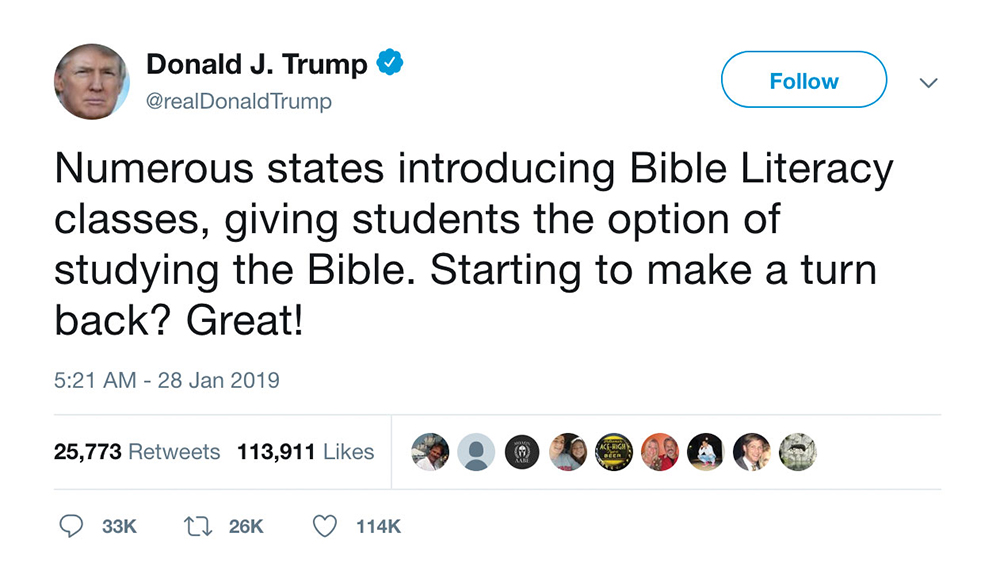

North Dakota Senate Bill 2136 would require public schools to offer a unit on the Bible, covering the Old Testament, the New Testament, or a mix of the two. One-half unit is required for graduation and another half-unit can replace a social studies requirement. The bill was overwhelmingly rejected (5-42) on Friday, January 25, but that didn’t stop North Dakota State Rep. Aaron McWilliams, the bill’s author, from going on Fox News on January 28 to promote it and similar efforts in other states. He claimed that his bill allowed schools to determine whether to offer the elective and allowed students to choose whether or not to take it, which is untrue. After he and the Fox commentator spent most (88 percent) of the segment defending Bible literacy, McWilliams briefly mentioned that his bill had failed before he added that we would be “establishing a religion of secularism within our school by not having anything else.” Moments after the television segment, President Trump, no doubt hoping to reach his evangelical base, tweeted:

Virginia Senate Bill 1502 would amend and reenact 22.1-202.1—which provides an elective “comparative religion class that focuses on the basic tenets, history, and religious observances and rites of world religions”—to add an elective teaching the Bible (any translation of the Old Testament, New Testament, or both). Similar to Florida’s, this bill mandates that “no such course shall endorse, favor, promote, disfavor, or show hostility toward any particular religion or nonreligious perspective.”

At present, no bill or legislator has mentioned how the teachers of these Bible literacy will be recruited, trained, and supplied with adequate resources. By the time students reach high school, they’re more likely to be questioning their own or their parents’ beliefs—either out loud or internally—so teachers may need to address a variety of questions, misinformation, and disagreements that require mediation. Teachers will also need to put aside their beliefs in order to teach objectively. This will be a challenge for the religious and nonreligious alike.

Even if the courses are focused on the historic and literary qualities of the Bible, the teachers are objective, and the students are respectful, having only a Bible studies elective available perpetuates the dangerous myth that the United States is a Christian nation, that Christianity is the default religion for all. To better understand how comparative religion can be taught in public schools, those making these decisions should consult the American Academy of Religion’s Curriculum Guidelines. Produced in 2010, the report acknowledges:

1) the study of religion is already present in public schools, 2) there are no content and skill guidelines for educators about religion itself that are constructed by religious studies scholars, and 3) educators and school boards are often confused about how to teach about religion in constitutionally sound and intellectually responsible ways[.]

As the world’s largest association of religion scholars, the AARC is well qualified to advise those who are pushing religious studies in public schools and by those who will implement curriculum if it comes to that. Religious studies should only be allowed in public schools if it educates students on people’s different perspectives of the world, fosters ways to develop a more inclusive society, and combats misinformation or proselytizing. Otherwise it’s unconstitutional and unethical.