The Selected Letters of Ralph Ellison

EDITED BY JOHN F. CALLAHAN AND MARC C. CONNER

RANDOM HOUSE, 2019

1060 PP.; $50.00

Reviewing a collection of letters by a writer can be a tricky business. The style, themes, and insights that distinguish the professional work are often absent when the correspondent is presumably more interested in revealing his or her innermost feelings and self. And so it’s almost impossible for a reviewer not to end up reviewing the author’s personality when writing about such letters—and what mere reviewer has the wisdom for that? (Certainly not this mere reviewer.)

But writing about the letters of Ralph Waldo Ellison (1913–1994), the author, most famously, of Invisible Man, is dicey for an antithetical reason. From 1936 until his death, Ellison kept copies of his correspondence. However, the letters from, I’d say, the late 1940s on are scrupulously conscious (a word quite meaningful to Ellison) and self-protective, even when he’s expressing love, lust, charm, or rage. It seems plausible that the wily Mr. Ellison was trying to prevent friends, enemies, admirers, and scholars from picking apart his psyche. He no doubt wanted to be apprehended on his own terms. (Who doesn’t?) And so I can’t help thinking that he’s currently looking down (forgive me, Humanist readers), having a good laugh over the hapless folks vainly trying to pluck out the heart of his mystery while reading this massive, often vexing book.

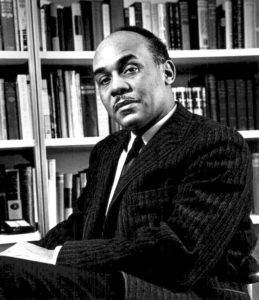

Ralph Ellison

Ellison was a black American and proud of it. (Invisible Man, which won the National Book Award in 1953, is the story of an unnamed black man searching for his identity—and America’s. Addressing the social and cultural experiences of black Americans, the book has touched a chord in readers of all backgrounds since its publication.) Born in Oklahoma City, Ellison’s father died when he was three years old. He, his mother, and younger brother were impoverished and would remain so for a very long time. Ellison’s letters, especially those written during the last part of his life, are quite sentimental about his early years in Oklahoma, but Arnold Rampersad’s Ralph Ellison: A Biography (2007) indicates that the artist’s looking back at those days was pervaded with a strong dose of romanticized reverie.

Ellison attended Tuskegee Institute (now University) but departed before graduating, “hounded out of college,” he says in a 1987 letter to his friend, the distinguished poet and translator Richard Wilbur, “by a homosexual dean of men.” The letters in this volume begin at Tuskegee; the early ones are mostly addressed to his mother and are invariably pleas for money and clothes. These entreaties reflect one of the major themes of the correspondence as a whole: Ellison’s penury, which lasted much of his life. I was shocked that even after the publication in 1952 of Invisible Man, which was a bestseller and never, I believe, out of print, his money woes continued until at least the late 1950s, when he began teaching at various colleges.

After leaving Tuskegee in the depths of the Great Depression, he moved to New York City intending to become a composer or a sculptor. But after befriending Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, and writers hired by the Federal Writers’ Project (it gave jobs to indigent authors), he switched careers, as it were, and decided to try his hand at fiction writing. Ellison also embraced Communism in the thirties. His letters from that decade contain a lot of trite Communist rhetoric, which must have embarrassed him later in life. He jettisoned the ideology in the forties after his intellectual interests broadened and became more sophisticated, and his friends came to include the literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman, the novelist Albert Murray, and the literary theorist Kenneth Burke. After Invisible Man’s publication, Ellison crafted the persona that he would present to the world—dignified, courtly, a bit stuffy. The letters he wrote subsequent to the novel’s success too often reflect this decorum, and while they probably thrilled the recipients, I frequently found them less than scintillating. I’m of the opinion that Ellison was one of this country’s most astute, perceptive students of the American scene and soul, but gentility simply isn’t the best vehicle for exploring those realms. So, for the most part he doesn’t explore them. Some of his acuity about our improbable country made its way into the letters. He remarks in 1991 that “as [Henry James] noted, being American was indeed an arduous task.” And in 1987 he says to a friend:

As you point out, American culture is most “American” in what lies hidden in its mixture of modes, thus it’s hard to tell who the hell had his hand in the mixing. Come to think about it, it’s getting harder and harder to figure out just who is most truly American, because it seems to boil down to who was most modified by the democratic process, be they black or white, than a matter of allegiance to flag, region, social class or racial identity. Perhaps that’s why many white Americans are so haunted by the possibility of a Negro turning up in the woodpile.

Generally, however, it’s frustrating that so much American history, politics, and culture of the last decades of the twentieth century go unexamined in Ellison’s letters. I’d love to have read his reflections on, for example, the end of World War II, the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the first Moon landing, Vietnam, Watergate, and on a lighter note, Truman Capote’s fabled 1966 Black and White Ball, which Ellison and his wife Fanny attended.

When Ellison does address fraught American issues, those letters often read like essays, and like the essays in his second collection, Going to the Territory (1986), they are usually so mannered they smother his shrewd, sage observations. I have nothing against a writer showing off (Invisible Man triumphantly brandishes literary styles), but while reading these letters I found myself in the odd circumstance of agreeing with the author’s opinions while aggravated by the grandiloquence. In various letters Ellison rebukes Edmund Wilson and Dwight Macdonald for diverse sins, but both were better writers of expository prose than Ellison. However Kenneth Burke, Ellison’s “rabbi” (“So you thought I was only a goy?” an amused Ellison asks his correspondent), was, ironically, a terrible writer; indeed, I found him unreadable.

I suggested at the beginning of this review that Ellison tried hard in his letters to protect his emotional and psychological privacy. The distressing exceptions are some 1957 letters to his second wife, Fanny, which discuss an affair he had. “There was, I admit, some shabby aspects to what I did but then passion makes its own rules,” he writes. “[T]he question is what is the hardest to forgive, the breaking of the rules or the existence of the passion itself?” Another letter, which is the only one in this collection that reads like stream of consciousness, is a plea for reconciliation but includes this: “I say this now without changing one bit of my belief that you were partially responsible for what happened here.” It was embarrassing, painful even, to read these letters; I felt I was eavesdropping on deeply personal matters that are none of my business. I also mentioned earlier that reviewers, in writing about a collection of a writer’s letters, aren’t competent to review the author’s personality. But reckless me, here I go anyway. In blaming “passion” and even Fanny for his adulterous behavior, Ellison comes off as a cad. I would never advocate censorship, but I wish I hadn’t read those letters. Anyway, they didn’t divorce.

Who is this book for? Academics, certainly. And presumably, people like me who’ve read most of what Ellison wrote that has appeared in book form: short stories, essays, interviews, and excerpts from his second, unfinished novel, including the book-length Juneteenth. Also Rampersad’s biography and a fair amount of criticism. Probably because of this background, I found little in the Selected Letters that I didn’t already know. This doesn’t mean that I didn’t find much in the letters that was obscure or puzzling, especially since the coeditor John F. Callahan’s section essays were more adulatory than helpful about nuts-and-bolts information, and there weren’t nearly enough explanatory footnotes. To be fair, there are good things scattered throughout; the literary gossip is (as always) fun. The critic Alfred Kazin is “a bit pompous”; Dwight Macdonald is an “ass”; Ellison disdains the famous essay by Susan Sontag, “Notes on Camp,” and so on.

A few more nuggets: Ellison persuaded his fellow National Book Award judges, including Kazin, to vote for Bernard Malamud’s The Magic Barrel as 1959’s best fiction of the year, which they chose over Lolita. (I mention this to show that even Ellison made mistakes of literary judgment.) In the late 1950s he attended at least one conference abroad (to Karachi, Pakistan) under the auspices of what a letter and the index call the Congress of Cultural Freedom. It was actually called the Congress for Cultural Freedom, but in any case, it was revealed in the 1960s that the congress was a CIA front. Did Ellison know or suspect this when he accepted the organization’s patronage? If he didn’t know until the public disclosure, did he feel duped? Intriguing questions (left unanswered by the correspondence and the editors). Ellison’s abiding fascination with literary style also occasionally comes through in the letters. When he talks, apropos of Henry James, of “the moral implications of fictional techniques,” I for one wish he had scrutinized the subject in depth.

A few more nuggets: Ellison persuaded his fellow National Book Award judges, including Kazin, to vote for Bernard Malamud’s The Magic Barrel as 1959’s best fiction of the year, which they chose over Lolita. (I mention this to show that even Ellison made mistakes of literary judgment.) In the late 1950s he attended at least one conference abroad (to Karachi, Pakistan) under the auspices of what a letter and the index call the Congress of Cultural Freedom. It was actually called the Congress for Cultural Freedom, but in any case, it was revealed in the 1960s that the congress was a CIA front. Did Ellison know or suspect this when he accepted the organization’s patronage? If he didn’t know until the public disclosure, did he feel duped? Intriguing questions (left unanswered by the correspondence and the editors). Ellison’s abiding fascination with literary style also occasionally comes through in the letters. When he talks, apropos of Henry James, of “the moral implications of fictional techniques,” I for one wish he had scrutinized the subject in depth.

It wasn’t easy being Ralph Ellison. Besides being broke for much too long, he was denounced by black nationalists in the sixties and seventies for not being radical enough, and the pressure from not being able to produce a second novel must have been brutal. (There is a tacit subtext in this book about that unfinished novel. After he became a literary celebrity, Ellison was so involved with lectures, symposiums, teaching, and public-spirited projects—e.g., the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, the Carnegie Commission on Educational Television—there didn’t seem to be a great deal of time left for novel writing.) Nevertheless, he comes off in the letters (and interviews, etc.) as an idealist about America and life in general, and this doesn’t seem to be a public pose. And so, dear reader, if you’re feeling gloomy about the nation’s current Babylonian captivity, a.k.a. Donald Trump’s administration, perhaps the following statements (written in 1986, near the end of Ellison’s life), from a man who understood the complexities of the human condition, will bring you some hope: “Life is of a whole, therefore we can’t achieve the good without coming to grips with the bad”; and—I’m particularly fond of this one—“No funk, no fun; no decay, no rebirth.”