Free Speech Aflame: The Humanist Interview with Greg Lukianoff

Greg Lukianoff is the president of FIRE—the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education. FIRE is a nonprofit educational foundation that supports free expression, academic freedom, and due process at U.S. colleges and universities. His book, Unlearning Liberty: Campus Censorship and the End of American Debate, was published in October 2012, and has been enthusiastically praised by luminaries such as Nat Hentoff, Nadine Strossen, Steven Pinker, and Daphne Patai. A graduate of American University and Stanford Law School, Lukianoff previously worked for the ACLU of Northern California, the Organization for Aid to Refugees, and the EnvironMentors Project. He’s published articles in the Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Boston Globe, Chronicle of Higher Education, and numerous other venues, and he regularly blogs at the Huffington Post.

The Humanist: First, congratulations on publishing your book and getting married in the same month. Talk about positive stress.

Greg Lukianoff: Thank you. Yes, it’s been pretty intense. But in a good way—both have been tremendously satisfying.

The Humanist: Tell us about your book, Unlearning Liberty. What’s the main premise?

Lukianoff: Well, for several decades, U.S. colleges have increasingly turned to censorship of both students and faculty. As a result, students are learning to withhold their opinions from each other, and are talking primarily to those with whom they already agree. They aren’t learning nearly enough about critical thinking, how to tolerate emotional discomfort during debate, or what free expression really means.

Lukianoff: Well, for several decades, U.S. colleges have increasingly turned to censorship of both students and faculty. As a result, students are learning to withhold their opinions from each other, and are talking primarily to those with whom they already agree. They aren’t learning nearly enough about critical thinking, how to tolerate emotional discomfort during debate, or what free expression really means.

The Humanist: You’ve done a great job in detailing the specific tools that colleges now use to censor—in fact, they’re so common that they aren’t even discussed very much.

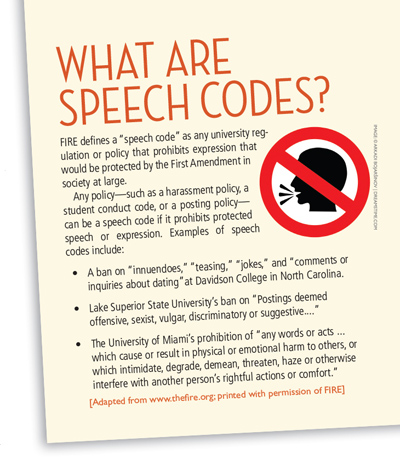

Lukianoff: Yes, their tools include speech codes, bans on anonymous fliers, limits on what can be said in classrooms, the elimination of due process, limiting campus protest to tiny “free speech” zones, the assertion of power over students’ off-campus speech, and more.

The Humanist: Let’s start with a real-life example from the book.

Lukianoff: One of the most ridiculous examples of college censorship occurred in 2007 at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. A student who was working his way through college as a janitor—a student in his fifties—was reading the book Notre Dame versus the Klan by Todd Tucker. It’s about the defeat of the Ku Klux Klan when they tried to march on the University of Notre Dame in the 1920s. The cover had a picture of the Klan rally that attempted that march, a famous historical photo. And he was found guilty of racial harassment because the book cover made another employee uncomfortable.

The student employee wasn’t allowed a chance to respond, he wasn’t allowed any chance to defend himself or explain that it isn’t a racist book. All that mattered was someone had taken offense, and there was nothing he could do to fight back. It was a book that the university actually had in their library, so they had already judged it acceptable.

It took the combined efforts of FIRE, the ACLU, and the Wall Street Journal to get the university to entirely back down.

The Humanist: He had been put on probation?

Lukianoff: Essentially, yes. But worse is the charge of racial harassment. If you go out looking for a job in the real world with that on your record, people could assume that you’re actually a member of the Klan rather than assume you were falsely accused of racism because you read a book about the defeat of the Klan.

The Humanist: You see such censorship as part of a historical context, right? I guess it’s connected with wanting to prevent people from behaving in ways that make other people feel uncomfortable.

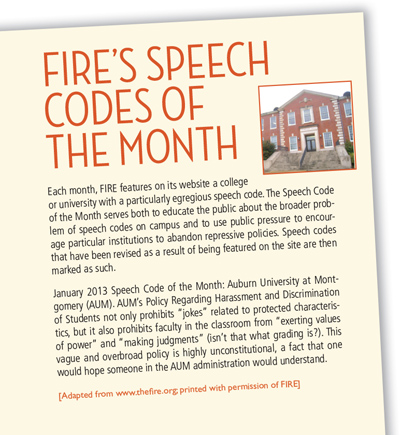

Lukianoff: Like a lot of censorship movements, the modern campus speech code movement was motivated, at least in part, by people who thought they were doing something kind or wise. And while we don’t have any illusions about some past golden age of free speech on campus, things were definitely better during the 1960s and ’70s. But starting in the 1980s there was a significant about-face with the genesis of speech code theory, which posited that if you really wanted a tolerant society, you had to clamp down on speech that could be hurtful or offensive on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, and the like. So universities started passing speech codes in the late ’80s, even though they were defeated roundly in the court of public opinion—both on the right and on the left—and there were many court challenges. Sadly, there are more speech codes in place now than there ever were in the 1980s and ’90s.

They’re based on the idea that censorship can promote a moral good. I find it so interesting that speech codes continue to be defended using this rubric of tolerance and care. But when you look at the cases I cover in Unlearning Liberty, you see that speech codes and censorship are no longer used the way they were initially intended. (Even if they were, they would still be unconstitutional.) But time and again, the arguments of tolerance and kindness get used to silence legitimate speech: punishing a student for writing an article that’s critical of Islamic terrorism, for example, or telling a professor that he can’t put a poster quoting the sci-fi western Firefly [that makes a reference to killing] outside his office door.

The temptation to misuse institutional power and the common desire of one group to silence other groups if they can are two important reasons why we need a separate amendment to protect freedom of speech. And that’s why you have to place censorship off the table. I watch college administrators toggle through rationales. They start with a response: “I’m offended by that expression,” “I don’t like that expression,” or “I don’t like you.” And then they proceed to their arsenal of tools: “Should I go with harassment in this case? A safety or student instability argument? Or should I go with some kind of time, place, and manner argument?” When censorship or punishment is disingenuously allowed in the name of tolerance, it gives speech codes a better reputation than they deserve.

The Humanist: Please talk about how the original doctrines of sexual harassment or racial harassment policies were never designed to prevent people from feeling uncomfortable. As far as I understand, they were designed to prevent or undo environments in which people could not pursue their own rights, such as to learn or work.

The Humanist: Please talk about how the original doctrines of sexual harassment or racial harassment policies were never designed to prevent people from feeling uncomfortable. As far as I understand, they were designed to prevent or undo environments in which people could not pursue their own rights, such as to learn or work.

Lukianoff: FIRE is extremely clear about this: we don’t believe that people should be racially or sexually harassed. But we’re always explaining that harassment is a serious pattern of behavior targeting someone for a characteristic like race or gender—sort of an extension of traditional anti-discrimination law. These newer doctrines addressed the reality that employers could get around anti-discrimination law by hiring women or people of color, but then making the workplace so miserable for them that they couldn’t continue working in it.

Unfortunately, the next step is rather predictable: eventually, this well-intentioned, narrowly defined idea ends up getting applied in ways that were never even vaguely intended. At Brandeis University, for example, a professor who’d been teaching Latin American studies for close to fifty years explained to his class where the epithet “wetback” came from, and he was found guilty of racial harassment.

The Humanist: What should he have said, “the ‘W’ word”?

Lukianoff: Some people apparently think so. Among the people who should be angriest about this are the very people who most believe harassment should be stopped, because when you dilute it like this and it leads to so many trivial examples, it causes people not to take the concept of harassment very seriously.

The Humanist: Not unlike if everything is called molestation, it trivializes real molestation.

Lukianoff: What unites sexual misconduct codes and sexual harassment codes and speech codes is that if you define things broadly enough, every single student on your campus is guilty of either a speech code violation or of sexual misconduct—which makes it very easy for administrators to then pick and choose who they want to target. This, of course, works out poorly for people who are different or unpopular, people who are oddballs, or in some cases students that the administrators simply don’t like.

The Humanist: One of the things you lament in your book is that differences of opinion are no longer viewed as opportunities to learn or as chances to think through ideas. Please say more about that.

Lukianoff: Speech codes and changed attitudes about freedom of speech have created all of these negative feedback loops for expression and critical thinking. As you censor unpopular opinions you end up with classroom environments where individuals can’t really speak their minds. You also end up with students mostly talking to people they already agree with. The research on this is very strong—when you talk to people you already agree with, it thwarts development of critical thinking skills, and it makes people much more confident in what they already believe. It tends to make people more adamant, and exacerbates the serious problem of groupthink.

If we’ve legislated politeness, and legitimized the idea that disagreeing with somebody could potentially hurt his or her feelings, why bother to discuss anything? We have to teach people that debate and discussion lead to better ideas—they allow us to be more creative and to develop critical thinking skills. Moreover, the idea that meaningful, meaty debates over the most serious issues can actually be fun has been badly damaged.

The Humanist: In the sixties such discussions were considered foreplay.

Lukianoff: Putting this weird energy around disagreement, dissent, satire, parody, devil’s advocacies, or thought experimentation makes everything so dreadfully serious. Students no longer appreciate the idea that the professor whose seemingly strange attitudes about everything from sex to religion to politics could actually be presenting an opportunity to dive into something interesting—as opposed to saying something another person’s fragile ego can’t handle.

The Humanist: I love this line from your book: “Political correctness has become part of the nervous system of the modern university.” You make a crucial connection between the intellectual habits that people are absorbing on campus and the degraded way democracy is now functioning.

Lukianoff: Again, universities need to return to the idea that it’s good for you to talk to the smart person you disagree with, it’s fun, and it’s a truly great habit that will make you more creative and thoughtful. If universities taught that, they could actually be pushing back against all of this mindless bipolarity and groupthink that’s damaging the country today. Instead, we’re super-charging people’s opinions by discouraging them from talking to people with whom they disagree.

The Humanist: One thing you’ve brought to my attention is the increasing campus policy of banning unsigned fliers.

Lukianoff: We see universities in a lot of cases trying to ban anonymous expression, going so far as requiring fliers to have names and other information about the students who write them. The College of William & Mary in Virginia is the country’s second oldest college, where some of our founders went. These very same founders went on to produce anonymous writings like the Federalist Papers, which had tremendous impact on our entire society and the world. So when you have campus administrators not believing there could possibly be value in anonymous speech, you have to wonder if they know the history of what Thomas Paine, Alexander Hamilton, or James Madison wrote uncredited.

Lukianoff: We see universities in a lot of cases trying to ban anonymous expression, going so far as requiring fliers to have names and other information about the students who write them. The College of William & Mary in Virginia is the country’s second oldest college, where some of our founders went. These very same founders went on to produce anonymous writings like the Federalist Papers, which had tremendous impact on our entire society and the world. So when you have campus administrators not believing there could possibly be value in anonymous speech, you have to wonder if they know the history of what Thomas Paine, Alexander Hamilton, or James Madison wrote uncredited.

The Humanist: How do you respond to universities’ claim that banning anonymous fliers makes people more responsible and less likely to just trash each other?

Lukianoff: Actually, I think there’s some truth in that. If people have to suffer the natural consequences of their speech, they’re typically less cavalier about what they say. At the same time, you can’t ban anonymous speech until people feel very confident that they can hold any point of view they want. As long as you can still get in real trouble on campus for having the wrong point of view, anonymous speech makes perfect sense—just as it did way back when saying what one believed could put your life or property in danger.

On campuses right now, students don’t and shouldn’t feel completely confident that they can express whatever opinion they want. And until every single speech code is gone, banning anonymous speech is a powerful form of censorship.

The Humanist: In fact it goes beyond that. You can now get into trouble for what you say off campus.

Lukianoff: Absolutely. Schools now have the power to punish students for what they write on Facebook or what they say at a political event or even a party off campus.

The Humanist: So how did FIRE become so powerful so quickly? I mean, at thirteen years old, it’s a relative upstart compared with, say, the ACLU.

Lukianoff: I think FIRE became influential so quickly due to a combination of things. Most importantly, there were so many abuses of power on so many campuses, and we were willing to challenge them regardless of ideology. When evangelical Christians get in trouble, FIRE is there. If Richard Dawkins is being investigated for speaking at the University of Oklahoma, FIRE is there. It was really a niche that needed to be filled.

[FIRE founders] Alan Kors’ and Harvey Silverglate’s idea that FIRE’s primary weapon would be public exposure rather than litigation was also very smart. Because, as Kors has said, universities cannot defend in public what they do in private. Our wonderful employees put in an awful lot of hard work, often on short deadlines. We pull in journalists and others from the local community, and alert the national media when there’s been an outrageous violation of rights. We’re very passionate about getting the word out.

The Humanist: What do you mean when you say that universities can’t defend in public what they do in private?

Lukianoff: So many university administrators get used to thinking of their school as their own personal fiefdom. One of the best examples involves the great First Amendment attorney Bob Corn-Revere. He’s currently litigating a FIRE case that started back in 2007 when a student at Valdosta State University in Georgia was expelled as a result of protesting the school’s decision to put up a parking garage. This student, Hayden Barnes, thought there were less expensive and more environmentally friendly ways to deal with campus transportation problems. However, VSU President Ronald Zaccari had been defeated by environmentalists in his goal to build the parking garage many years before, and he wasn’t going to let that happen again.

Barnes wrote a letter to the school’s newspaper, called members of the Board of Trustees to respectfully explain why they shouldn’t vote for the parking garage, and he posted a collage on Facebook satirizing what he dubbed the “Zaccari Memorial Parking Garage.” The collage featured images of smog, an asthma inhaler, and a “no blood for oil” logo. The “memorial” part of the title was a jab at Zaccari’s claim that the parking garage would be a proud part of his legacy.

So Zaccari kicked Barnes out, claiming that the collage—because it used the word “memorial”—was a threat on his life, as memorials usually appear after a person’s death. Various administrators tried to explain that he couldn’t expel the student without due process, also suggesting that Barnes wasn’t a threat to anybody. They even went into his medical records, and the campus counseling center verified that he wasn’t a threat. (Incidentally, he’s a nonviolent Shambhala Buddhist and a decorated emergency medical technician.)

Court documents suggest the Facebook collage was discovered after Zaccari had decided to expel the kid. Regardless, nobody believed Barnes’ speech posed an actual threat, and the law is clear that you can say things much more offensive than “memorial parking garage” on college campuses, and that you have to provide expelled students due process.

[Update: On February 1, 2013, at the Huffington Post, Lukianoff reported: “Earlier today, a federal jury in Georgia found former Valdosta State University (VSU) President Ronald Zaccari personally liable to the tune of $50,000 for violating the due process rights of former student Hayden Barnes.]

The Humanist: FIRE periodically defends students’ religious beliefs that some humanists—or non-humanists—would find hateful. Why?

Lukianoff: Personally, I’ve been an atheist since seventh grade. And FIRE was founded by two non-religious civil libertarians. All of us believe in the entire First Amendment, and that includes the establishment clause and free exercise clause.

So we’ve defended Muslim student groups and evangelical Christian student groups, some of whom are being kicked off campus because they believe that homosexuality is sinful. I don’t agree with that point of view, and I both hope and believe that such views will eventually be abandoned. But I challenge my friends who support expelling such groups: Do we really want to live in a society that can try to coerce somebody into changing their theological point of view just because it’s unpopular?

Our founders learned from Europe’s religious wars that the government should stay out of establishing a theocracy, deciding matters of theology, or interfering with people’s faith.

I understand the frustration on campus—some people want evangelicals to change their minds on issues like sexual morality. But you’re not doing that cause any favors if your solution is to kick those students off the campus. It probably hardens their point of view, and turns the narrative from “We have an idea that many people find objectionable” into “We’re being exiled for our points of view.” So, in addition to the strategy being wrong, I think it can backfire.

The Humanist: Intolerance—say of another’s code of sexual morality—is assumed to be a bad thing on campus because supposedly it creates an environment that makes other people uncomfortable.

Lukianoff: Yes. The question of making people uncomfortable versus discriminating against them is a distinction that I draw all the time. There’s a big difference between discriminating on the basis of an immutable characteristic, and opposing on the basis of a belief. Discriminating on the basis of an immutable characteristic like skin color or sexual orientation is something that should be challenged, as this discrimination prevents others from exercising their rights. But belief is intertwined with expression and civic integrity. Democratic societies need to nurture and protect people’s right to believe anything they want, no matter how distasteful it may be to others, even if those others are in the majority.

The Humanist: Thank you for your work with FIRE, and for writing an important book. I know there’s a Zen saying you use to summarize the importance of nourishing disagreement and critical thinking on campus.

Lukianoff: Yes, it goes like this: “Great doubt, great awakening. Little doubt, little awakening. No doubt, no awakening.”![]()