Adrift At Sea A Clash of Cultures, A Question of Faith

Seven days adrift in the Indian Ocean on a broken-down motorboat, two American women and two Indonesian fishermen face massive swells, intense sun, and a dwindling supply of food and water. With no land in sight and diminished hope for rescue, a decision must be made.

Back in California during this summer of 1985, I’ve just returned from a work project in South America. One of the women on the boat, Judy Schwartz, is my girlfriend, and I’m totally unaware of the dire situation she shares with her good friend since high school, Rickey Berkowitz. Since both women work in education and enjoy summers off, they had decided to fulfill a lifelong dream of extensive travel to Australia, New Zealand, and Indonesia. Judy and I considered our time apart good for us—will marriage be our next step?

It’s Saturday afternoon, and I’m enjoying Phil Collins’s new album, No Jacket Required, with a friend I’m sharing an apartment with for the summer when the phone rings. It’s Judy’s brother—the women have not been heard from for several days and may be missing. What? Simple communication error, I think to myself. But as the days pass, the situation becomes desperate. Sources say the women hired a motorboat operated by two young Indonesian fishermen to take them to the Ujung Kulon island nature preserve just off the coast of Java. But they never made it.

A week later, I receive the most difficult call of my life from Judy’s sister, who tearfully informs me that the women’s parents, who have been in Jakarta for two weeks overseeing a search conducted by the American embassy, are returning home in despair. The search has come up with nothing. The boat must have broken down in the calm waters of the Sunda Strait then drifted out to sea where it capsized. All four are presumed drowned.

Days later I attend a somber gathering of family and friends at Judy’s parents’ house for a memorial honoring the lives of both women. We share pictures and stories. We even laugh. Judy’s mother maintains stunning composure with the exception of one moment that slices through the crowd when she yells, “I can’t believe she’s gone!”

But no bodies—nor a boat—have been found, so I decide to fly to Jakarta on my own to tie up any loose ends, to keep vigilant for anything that might suggest a different outcome. Aware of the odds against this, my trip will be more about catharsis and closure.

On the other side of the world, rolling on twenty-foot swells of the Indian Ocean, four people have come to the hard conclusion that a rescue boat isn’t coming and may never have been launched at all. This reality elicits reactions governed by two different ways of seeing the world. Since the men speak no English, communication between the pairs involves pantomime and gesture. Every nuance, gaze, and even body movement into another’s personal sense of space invites misinterpretation. The men are ostensibly Muslim, but their beliefs are likely influenced by the long history of Java. Even the color of Judy’s shirt—green—likely contributes to the men’s despair since it’s the forbidden color of the Queen of the Indian Ocean, Nyai Loro Kidul, who claims the souls of fishermen every year. The men fall into a gloom, perhaps a brand of fatalism—they guzzle water frequently and recklessly, letting it drip down their cheeks. They huddle under the hull and pray.

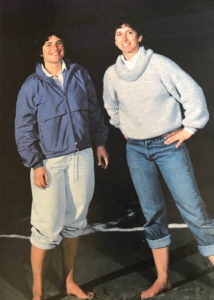

Rickey Berkowitz (left) and Judy Schwartz (right). Photo courtesy Judy Dietel Camarota

Judy and Rickey, bewildered by the men’s resignation, form an ambitious plan. Rickey rations the boat’s scant supply of food and water while Judy uses a Swiss Army knife to sew together two sarongs and a tent fly to build a sail. They use a bamboo pole for a mast, securing its base in a bucket of sea water. Judy has a compass, and she charts a confident direction toward land. She’s an avid windsurfer, and she sets the boat on a barely perceptible tack in the light winds. Rickey then takes over the compass and directs the course with unrelenting discipline. When the compass becomes difficult to see at night, they are aided by the Southern Cross.

The women combine strengths to become a team of complementary forces. Judy struggles to reorient the boat at one point and nearly falls into the water where currents could whisk her away. Rickey assumes tough command of her duty as “ration master.” Both women’s backgrounds—Judy is a teacher and Rickey is a school psychologist—provide intuition and reason during tense moments with the men, one of whom wields a rusty machete while demanding more food or water. Uncomfortable with two strong-willed women who have set the plan and the ground rules, he resorts to the machete as an explicit symbol of dominance.

But the men, naturally lean like most young Javanese males, quickly deplete their reserves and become weaker as the days go by, allowing Rickey to sneak the machete into her possession. Noticing his machete missing, the fisherman looks up to find Rickey smiling in defiance while holding it up. He picks up a piece of board he’s hacked from the boat and faces her, but then backs down.

After the four drink their last drops of water, they wait two days before it rains. The men clamber from under the hull and lick droplets from the windshield. The women use an extra poncho to funnel water into containers and replenish their supply—a move that could make all the difference.

On the evening of the twenty-first day, after land has been in sight for a grueling seven days of snail-paced plodding, they finally reach the shores of Sumatra. A wave capsizes the boat, and Judy curses to herself in roiling surf, damned if I’m going to die here after coming all this way. She surfaces, gasps for air, and clings to the capsized boat. Calling for Rickey, she spots her beloved friend clinging to the other side, and Rickey calls back. Finally, Judy’s feet touch bottom, and somehow, somehow, they all get to the beach without being sliced to death on reef coral. Struggling on wobbly legs they collapse on the sands, exhausted, and fall asleep until morning when villagers find them and guide them to food, water, shelter, and eventually to a phone.

In California, I’m within an hour of leaving for the airport to catch a flight to Jakarta, but I have one last item to scratch off my list—a call to the embassy to confirm my upcoming arrival. The official on the other end of the line, who’s spent two weeks with the women’s parents during the search, is ecstatic. She has just confirmed the news—“Judy and Rickey are fine!” she belts.

Just two days later on a hot September afternoon, I’m standing in a spacious greeting room at the Los Angeles International Airport gathered with a crowd of family and friends including Judy’s and Rickey’s parents and my own. Also present are several equipment-laden members of the news media. Many are convinced they’re about to witness a miracle.

The story of two California women surviving for twenty-one days on a broken-down motorboat on the Indian Ocean with two Indonesian fishermen was big news in September of 1985. Photo courtesy Judy Dietel Camarota

An official, standing by the doors to the tarmac with one hand on the lever, announces that the women have arrived and are about to enter. A hush comes over the crowd. We stand in anticipation, some tense, some weary, but everyone with their personal sense of joy. When the doors open, they burst open. Loud screams follow, almost terrorizing, but these are screams of extreme relief and happiness. Judy and Rickey, looking overly thin, tanned, and pockmarked with healing scratches and bites, reunite with their parents in a firm embrace and muffled sobs. They cry, tighten their hugs and rotate as a unit, six people radiating human magnetism so strong that it’s almost uncomfortable for the rest of us. Struck with awe, we stand back to allow the six their paramount moment of intense emotion.

Reactions to this story are mind-boggling, even at times intimidating. The women make appearances on The Today Show, Ted Koppel’s Nightline, and The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. My brother adopts the habit of introducing Judy in the voice of Ed McMahon (“Heeeeeeeeerre’s Judy!”).

As Jews, Judy and Rickey celebrate the major Jewish holidays—Passover, Yom Kippur, and Hanukkah—but Judy considers herself more a part of a unified people than religious. She places no emphasis on supernatural power, and yet she’s asked a common question: Did her ordeal strengthen or modify her belief in God?

Judy, being a realist, a matter-of-fact kind of woman, simply tells them no. For both women, the ordeal, in fact, boosted their faith in themselves. While only four people witnessed first-hand those twenty-one days adrift on a floating island of unmixable cultures and religious beliefs, one simple fact is unabashedly indisputable—they survived.

On December 26, 2004, the Indian Ocean claimed 230,000 lives among fourteen countries following the magnitude 9 earthquake off western Sumatra that triggered one of the most devastating tsunamis in history. Did God provide Judy and Rickey with rain at the moment of their most intense thirst? The question not only sounds silly, but heartless and insensitive when we consider those 230,000 people, many with unquestioning faith in their god, many who likely prayed in the moments before their deaths. Would an all-loving God give special attention to four people and flatly deny 230,000?

Drawing on bonds of deep friendship galvanized by time, these two women combined attributes to reign over the forces of nature and persevere with unrelenting discipline to reach renewed contracts on life. This manifestation of human essence and fortitude is far more attractive to me, more real and uplifting, than any construct of a so-called benevolent God who picks and chooses on a whim.