Changing Times in America’s Execution Capital

A father’s successful struggle to spare the son who killed the rest of the family highlights how Texas, historically America’s top executioner, is moving away from the death penalty to reflect a national trend.

With less than sixty minutes before he was due to die by lethal injection, Thomas Whitaker’s death sentence was commuted to life in prison without the possibility of parole by the Republican governor of his home state of Texas.

Explaining his decision, Governor Greg Abbott cited the plea for clemency by Whitaker’s father, Kent Whitaker, to spare his son—even though, according to the prosecution, in 2003 Thomas Whitaker arranged for a friend to kill his father, mother, and brother to get the family inheritance. Despite being wounded in the chest, Kent Whitaker survived, hearing the two shots that killed his wife and other son.

During the murder trial Kent Whitaker begged the prosecution not to pursue the death penalty.

“I am a law and order guy,” he says. “I used to support the death penalty, but you can’t blindly believe what officials say—it’s important to keep a healthy skepticism and speak out if they overstep. Texas will always be a conservative state, but that doesn’t mean it’s always right to apply the harshest penalty.”

Hence Kent Whitaker never gave up hope and continued to try and save his son, even though he realized the odds were stacked against both of them. Since 1976 when the US Supreme Court upheld capital punishment (it was suspended in 1972), 1,469 people have been executed in the US—548 in Texas. Harris County has the highest number in the state and is referred to as the execution capital of America. Furthermore, clemency is exceedingly rare—before the Whitaker decision, more than ten years had passed and nearly 150 people had been executed since a Texas governor last spared an inmate from a death sentence. The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles, which needs to approve a clemency case before it goes to the governor for the final verdict, has historically proved just as hard to sway.

“Victims’ rights should mean something in this state, even when the victim is asking for mercy and not vengeance,” Kent Whitaker said at a press conference at the Texas State Capitol just before the favorable unanimous vote in favor of clemency came in from the board on February 20, 2018, leaving less than forty-eight hours for the governor to make up his mind.

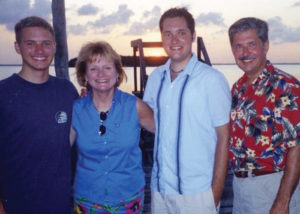

Kevin (from left), Tricia, Thomas, and Kent Whitaker pose in an undated family photo. Photo courtesy of Kent Whitaker

The Whitaker clemency case is emblematic of the fact that, despite the Lone Star State’s history of tough justice, both executions and the awarding of death sentences are actually decreasing in Texas, reflecting a nationwide trend often missed amid dramatic headlines about executions. Resistance to the death penalty is increasing even among those who have traditionally supported it, like conservatives and evangelical Christians.

“The culture now is different,” says Kristin Houlé, executive director of the Texas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty. “There isn’t the same appetite for it from either the public or elected officials.”

Executions in Texas peaked in 2000 when there were forty. Last year there were seven, matching 2016 for the lowest number of executions in two decades, amid a national total of twenty-three. Meanwhile, for the last three years Harris County hasn’t executed anyone.

“Whatever happens in Texas does have a ripple effect because it has been so notorious for its death penalty practices,” Houlé notes. “So any move away has a significant impact on the rest of the country.”

During the twentieth century, only seven US states abolished the death penalty, as did the District of Columbia in 1981. But since New York abolished the death penalty in 2004, six other states have done so. (Although in 2016, Nebraska voters approved a ballot question reversing the legislature’s repeal of the death penalty and restoring capital punishment in the state.)

Fewer than one-tenth of 1 percent of counties in the US accounted for more than 30 percent of all the death sentences imposed nationally in 2017, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Three outlier counties—Riverside, California; Clark County, Nevada; and Maricopa, Arizona—imposed twelve death sentences. The information center also reports that between 2013 and 2017 there has been a 48.5 percent drop in the number of new jurisdictions imposing death sentences.

According to the results of a 2017 Gallup poll, 55 percent of Americans say they are “in favor of the death penalty for a person convicted of murder,” down from a reported 60 percent in October 2016. The 2017 results reflected the lowest level of support for the death penalty in the US since March 1972—just before the Supreme Court decision in Furman v. Georgia declared the nation’s death-penalty laws unconstitutional. The peak for support of the death penalty was in 1994, when 80 percent of Americans were in favor of it.

“We had a moment when it seemed we might follow the Western European countries that were abolishing the death penalty in the 1970s, but then it became a political issue, with politicians running on a ticket of being tough on crime, appealing to that cowboy mentality Americans are famous for—that was the shift, which coincided with the war on drugs,” says Jennifer Thompson, who founded Healing Justice, an organization focused on recovery and healing for those harmed by wrongful convictions. She was prompted to do so after her rape case resulted in an innocent person being sent to prison while the true perpetrator remained free to commit additional crimes. “Fear is a great social stirrer, and it created a momentum that people got pulled into.”

Campaigners against the death penalty demonstrate in Texas. Photo by Texas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

The shift in opinion today follows decades of death penalty use, during which time it has proven exorbitantly expensive compared to putting someone in prison for life, ineffective in making society safer, and open to manipulation from ambitious prosecutors and old-fashioned human error, observers say.

“More people know about the risks of innocent people being executed after TV programs like 60 Minutes,” says Heather Beaudoin with Conservatives Concerned About the Death Penalty (CCADP). “They’re thinking, wow, this can happen—are we willing to risk it?”

Since 1973 at least 160 people have been freed from death row after evidence revealed that they had been wrongfully convicted. That’s almost one person exonerated for every ten who’ve been executed. Other concerns include drug shortages for lethal injections adding to the bureaucratic maelstrom, increased mistrust of government, and botched executions leaving those in attendance such as the victims of crimes and prison guards traumatized. Fiscal conservatives are also increasingly bristling at the enormous costs involved.

“Many people believe that the death penalty is more cost-effective than housing and feeding someone in prison for life. In reality, the death penalty’s complexity, length, and finality drive costs through the roof, making it much more expensive,” reports CCADP. “Capital punishment is an inefficient, bloated program.”

A 2017 report called “The Right Way” sponsored by CCADP shows a surge in the number of Republican lawmakers who sponsored death penalty repeal legislation at the state level. The report highlighted how from 2000 to 2012 it was rare, but in 2013 the annual number of Republican sponsors more than doubled. By 2016, ten times more Republicans sponsored repeal bills than in 2000. Meanwhile, more than 67 percent of the Republicans sponsoring death penalty repeal bills did so in red states.

“The issue is gaining ground and more traction in conservative circles. Soon we’ll see a bipartisan coalition in Texas and then across the country to look at the death penalty differently,” says Joe Moody, chairperson of the Texas House of Representatives Criminal Jurisprudence Committee, adding that his previously long-held belief that the death penalty had a place as a form of punishment has evolved—he no longer thinks it’s relevant in the criminal justice system. “Nothing happens overnight, especially in Texas, but to have momentum moving forward is quite a victory at this point.”

Politics and religion are often inseparable in conservative states like Texas, with politicians routinely calling for prayers and quoting scripture. Kent Whitaker says his Christian faith helped him forgive his son for his heinous crime. Most religious denominations, including the Catholic Church, are anti-death penalty, but that doesn’t stop some governors from going against the teachings of their respective churches regarding the sanctity of all life, and thereby holding the contradictory positions—in the eyes of their churches and of many others—of supporting the death penalty while being pro-life when it comes to abortion. Governor Abbott has said that the difference between abortion and the death penalty is “between innocent life and those who have taken innocent lives.” Many Americans in conservative religious states have grown up with the adage of “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth” from the Bible’s Book of Exodus as a guiding principle in justice, observers note.

“America is the only place where you can be pro-death, pro-guns, pro-war and still call yourself pro-life,” says Shane Claiborne, a prominent Christian activist and best-selling author. “The death penalty wouldn’t have survived in the US if it weren’t for evangelical Christians. Where evangelical Christians are most concentrated is where the death penalty survives. The Bible Belt is the Death Belt.”

The death penalty has historically been abolished in states that are more secular leaning, Claiborne notes, though now younger evangelicals in states like Texas are increasingly embracing a pro-life interpretation that goes beyond the confines of the abortion debate to include the Black Lives Matter movement, immigration, and those on death row.

At a legal level in Texas, life without parole as a sentencing option in capital cases has played a significant role in decreasing the number of death sentences and executions since its introduction into its courts in 2005.

“When you sit with a victim’s family and say it could take ten years for an execution or they can be done with it now [through a life sentence without parole], they say they want to move on with their lives,” says Texas criminal defense lawyer Keith Hampton, who represented the Whitaker clemency case.

Another change in the Texas criminal justice landscape that’s had an impact, Hampton says, is increasing skepticism about gauging the “future danger” a felon poses to society, which plays a critical role in the awarding of death sentences in Texas and Oregon.

“When it comes to so-called lethal prediction you might as well gaze into a crystal ball, the predictions are that unreliable,” Hampton says. “It’s a phony issue and a false question: if juries have just seen bloody pictures and all the other evidence and are then asked if the person will be dangerous in the future, what do you think they will say? But studies show, and prison staff report, that those serving life sentences are the best behaved.”

As a result of these changes, Hampton explains, prosecutors know juries are less willing to tolerate the pursuit of a death sentence and the additional expense and time it involves.

This was an extremely difficult bill to pass in Texas,” says Ian Randolph, who in 2005 was the legislative director for Senator Eddie Lucio, the author of the life without parole legislation.

The main opposition came from the prosecutors from the urban counties in Texas, particularly from Harris County. However, we had a few issues in our favor at the time: public faith in the death penalty had been in decline, the Supreme Court decision eliminating the use of the death penalty for minors, and a falsifying evidence scandal in the Harris County crime laboratory. This bill was all about bringing certainty to victim families—certainty by ensuring the perpetrator was locked up, eliminating a long capital punishment appeals process and possible future parole hearings while also allowing for exoneration if a prosecutorial mistake had been made.

Despite Texas’s punitive reputation, Houlé notes it was the first state to pass legislation giving defendants access to the courts if the science behind a conviction changed or was debunked, and it has led the way nationally at compensating those wrongfully incarcerated.

At the same time, however, trends such as racial bias in the Texas courts remain a concern. Over the last five years, 70 percent of death sentences have been imposed on people of color—more than half of these sentences were given to African-American defendants, according to TCADP. Also, though less than 13 percent of Texas’s population is black, they constitute 43.8 percent of death row inmates, according to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

Death penalty critics also highlight how arbitrarily it is applied based on factors such as a crime’s location or the whim of a district attorney. Whitaker’s clemency petition noted how the actual shooter was given a life sentence after pleading guilty to murder, while the getaway driver agreed to a fifteen-year plea deal and testified against Whitaker, who got the death penalty.

Those who support capital punishment counter that the decreasing death sentence and execution numbers are misleading as a gauge of public sentiment. They point out that the numbers also reflect a nationwide drop in murder rates, and that the death penalty continues to play an effective role. “Watching an execution is the most mentally draining experience, but it should be utilized for those who commit the most heinous, diabolical, despicable crimes known to man that cry out for the ultimate punishment,” says Andy Kahan, a crime victim advocate for the city of Houston, who has accompanied victims to witness eight executions. “Everyone has a right to disagree. I wouldn’t be surprised if the death penalty eventually goes. The law is subject to change. Everything comes in cycles.”

Both sides in the death penalty debate cite studies supporting respective claims about the death penalty achieving or not achieving deterrence—currently studies supporting the latter appear to have the upper hand.

“Anyone who says it has been definitively proved that the death penalty has no deterrent effect either doesn’t know what they are talking about or they’re lying,” says Kent Scheidegger, legal director of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, which has supported death penalty cases throughout the country. “The debate over studies supporting its deterrent effect is whether they have sufficiently shown it.”

The majority of death penalty states have murder rates that are higher than states that have abolished capital punishment, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Taken collectively, states with the death penalty have had higher murder rates than states without the death penalty every year from 1990 to 2016.

“The sides can disagree over whether it has any deterrent effect or not, but if it’s never carried out then it certainly won’t have any effect,” says Shannon Edmonds, a staff attorney with the Texas District and County Attorneys Association (TDCAA). In Texas, Edmonds notes,

the attitude has been, if we have the death penalty then we might as well use it, unlike in California, where they have the death penalty but also a booming death row population because the state won’t carry out executions. Only this can be said with any certainty about the deterrent factor: no one really knows as there are too many moving parts to factor in. We do know that while people argue about deterrence, the death penalty does deter the person on whom it is carried out.

While American public opinion appears to be increasingly swinging behind the anti-death penalty movement, it could always be swayed the other way—as illustrated by the reinstatement of the death penalty in Nebraska in a 2016 repeal measure.

“What will be interesting to see is whether the trend changes in the next two years, as the murder rate in Texas increased in 2015 and 2016,” says Edwards, adding that while Texas has pledged to recognize victims’ rights, ultimately, capital cases are about something else. “The victim’s wishes don’t control the outcome—their interests don’t trump the interests of the rest of society, which is who the state is representing. Often women in domestic abuse cases don’t want to prosecute, but the state continues to prosecute for the sake of the community.”

After the decision by the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles on Thomas Whitaker was announced, Fred Felcman, the original prosecutor in the Whitaker case, said the board had been swayed by the father’s activism, and appeared not to take into account the large number of other people affected by the murders, including the victims, the county, the jury, and family of Kent’s wife Tricia. He added that the board also disregarded testimony from psychiatrists and their own investigators who said Thomas Whitaker was manipulative.

Kent Whitaker argues that Thomas is a changed person from the twenty-three-year-old who in December 2003 came home from dinner with his family knowing that his roommate Chris Brashear was waiting there to kill them, according to court documents. On death row he has become a model prisoner who looks after others, his father says. Death row inmates and former prison guards sent letters to the parole board attesting to Whitaker’s good character.

Thomas Whitaker was already in the death chamber’s holding cell, along with his father on the other side of a glass partition, when the governor’s decision came down. According to Jason Clark, a spokesman for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, Thomas said he was thankful for the decision, though not for himself but for his dad.

“I deserve any punishment for my crimes, but my dad did nothing wrong,” Whitaker said, according to Clark. “The system worked for him today, and I’ll do my best to uphold my end of the bargain.” Whitaker had voluntarily waived all claims to parole as part of the clemency plea, meaning he will spend the rest of his life behind bars.

“I believe time has proven that we were right in passing life without parole,” Randolph says. “The use of the death penalty has declined. Public faith in the death penalty continues to erode and we have had numerous exonerations. Victims’ families and Texas juries deserve this option in these very difficult cases.”

In late February, the Alabama Department of Corrections attempted to execute death row inmate Doyle Lee Hamm. The United Nations had called on the US to stop the execution due to the man’s deteriorating medical condition. Then, when the state followed through and punctured Hamm over a dozen times trying to find a vein, they had to abort the execution. The UN and human rights activists have called this torture.

Meanwhile, the state attorney in Broward County, Florida, has announced that he intends to seek the death penalty in the Parkland school shooting case, in which nineteen-year-old Nikolas Cruz has been charged with seventeen counts of murder and seventeen counts of attempted murder during his rampage at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in February. While many critics of the death penalty argue that society simply doesn’t need it to ensure effective jurisprudence, some also allude to other more intangible though equally resonant ramifications of carrying out executions.

“It’s unhealthy socially; it gives a mirage of justice, in that you think that by killing the criminal there will be closure, but that doesn’t happen,” defense attorney Keith Hampton concludes. “It is socially self-defeating. It is society admitting it has failed.”