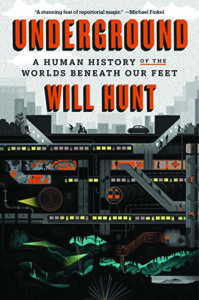

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds beneath Our Feet

BY WILL HUNT

SPIEGEL & GRAU, 2018

275 PP., $27.00

Underground is a strange little book, and not just because it reveres caves, catacombs, and sewers—the earth’s mantle below us. Will Hunt not only revels in subterranean geography and its attendant mythologies, he perceives them as cabalistic, indeed numinous. And though I reject the author’s subsurface theology (the only word that seems appropriate), I still found Underground entertaining and—dare I say it?—rather charming. Such is the devious power of good writing.

I might as well get my full disclosure out right now, because it at least partly explains my antipathy toward Underground’s subject: I’m claustrophobic, and hate and fear enclosed spaces. (I long ago lost the battle with my instincts to ride New York City’s subways.) Hunt is certainly not afflicted with similar serotonin treachery, for which I grudgingly admire him.

The author’s love affair with what lies beneath our feet began when he was sixteen and living in Providence, Rhode Island. A teacher told him about an unused tunnel in Hunt’s neighborhood, and he and some friends decided to find and explore it. Which they did, and Hunt become addicted (in a benign way) to the experience. “I came to love the underground for its silence and for its echoes,” he writes. “I loved that even the briefest trip into a tunnel or a cave felt like an escape into a parallel reality.” What Hunt found most captivating were the “dreamers, visionaries, and eccentrics that the underground attracted….Down in the dark, I thought I might find a perverse kind of enlightenment.”

Underground chronicles Hunt’s adult search for that perverse enlightenment, and a quirky journey it is. But he’s an engaging guide through his subterranean adventures, adventures that range across (or to be more accurate, through) the planet. He and some friends traverse Paris through the city’s underground infrastructure, where they meet fellow subterrestrial pilgrims (“cataphiles” they’re called, at least in Paris), and reconnoiter peculiar evidence of people determined to leave their mark in this tenebrous turf. One of the most bizarre examples of those latter encounters—it is the first of a number of surreal scenes in the book—takes place in a chamber that a cataphile calls “La Plage” (“the beach”—there is sand on the ground). Among other presumed attractions, La Plage contains a copy of Hokusai’s Great Wave off Kanagawa and a huge sculpture of a man with upraised arms. Hunt also endures another caper beneath Paris that isn’t so amusing: he and two friends get lost and are lucky to have gotten out alive.

Hunt knows his relevant science, but he’s also clearly a romantic. He travels to the Pyrenees, between France and Spain, to view “the most spectacular, most bewildering, and the most deeply hidden artwork anywhere in the world: les bisons d’argile, the clay bison.” When Hunt sees the bison, he cries. (There’s a photo of them in the book. They don’t look so majestic to me, but perhaps I’m a philistine.) These two artifacts were created 14,000 years ago by the provocative Magdalenian culture, which Hunt adeptly limns. And the machinations—and luck—involved in his arranging to see the bison (they’re located in a cave on a private estate) make for a droll story.

Hunt knows his relevant science, but he’s also clearly a romantic. He travels to the Pyrenees, between France and Spain, to view “the most spectacular, most bewildering, and the most deeply hidden artwork anywhere in the world: les bisons d’argile, the clay bison.” When Hunt sees the bison, he cries. (There’s a photo of them in the book. They don’t look so majestic to me, but perhaps I’m a philistine.) These two artifacts were created 14,000 years ago by the provocative Magdalenian culture, which Hunt adeptly limns. And the machinations—and luck—involved in his arranging to see the bison (they’re located in a cave on a private estate) make for a droll story.

The Maya, who dominated the Yucatán Peninsula, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador from 250 CE to 950 CE, were, in Hunt’s estimation, “underground obsessives, a people whose very existence depended on their relationship to caves.” Naturally, Hunt decides he has to investigate their former realm. He and Holley Moyes, an archaeologist and expert in Mesoamerican culture, enter a cave in Belize called Actun Tunichil Muknal, the “Cave of the Crystal Sepulcher,” and swim through the cave’s river until they reach the Crystal Maiden, a skeleton of a twenty-year-old woman who had been sacrificed (along with fourteen other people) to Xibalba, the Mayan underworld, in order to fend off drought. Hunt imagines what the ancient rituals might have been like. His conception, fairly gothic and not grounded in any scientific evidence as far as I could tell, reminded me of some of the macabre scenes in Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. Hard-hearted skeptics will be pleased to learn that the ceremonies didn’t thwart the drought.

Underground is nicely done, interesting and deftly crafted. I feel somewhat churlish for citing my sundry problems with a book that is intriguing and means well, but the author’s worldview and mine differ—and so onward and downward. An index and bibliography would have been helpful. Hunt’s forays under New York and Paris were illegal. Perhaps I’m a prig, but I don’t think that breaking the law in this fashion is winsome. For example, New York’s subway system is notoriously shambolic, and the police and transit personnel have better things to do than keep an eye out for gadabouts who get a buzz schlepping through train tunnels. In a similar vein (pun intended), I don’t understand the author’s idolizing of a New York graffiti tagger called REVS, who, among other vandalistic endeavors, left “diary” entries on the walls of the subway. New Yorkers of a certain age will indignantly remember REVS’s stupid, crude scrawls, which seemed to deface every sliver of the city. This character wasn’t an artist or an author, he was anomic.

I’m peeved that Hunt doesn’t mention my favorite urban legend: alligators in the sewers. He must have heard of it since he’s lived and apparently still lives in New York City, where it’s a persistent, endearing local superstition. (I’m sure this particular tall tale appears elsewhere, but it’s so perfect for New York, being a combination of the weird, preposterous and sinister. The New York-alligator nexus motivated Thomas Pynchon, whose novel V. is highly overrated but does have one good episode: a slapstick hunt for albino alligators in New York’s sewers.) I would have thought that Hunt, who is fascinated by the city’s nether regions, would have jumped at the chance to explicate the hidden meanings and implications of the alligator myth. I’m also disappointed that he doesn’t discuss any of the literature that wields underground imagery as a metaphor for modern humanity—Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground and Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, to name two.

Hunt’s passion for all things underground often segues into a sacralization of subterranean landscapes and the lore and rites that have historically been associated with them. “Our connection to caves,” he writes near the end of the book, “may well be our most universal, most deeply inscribed, perhaps our original religious tradition—which is to say it casts a long shadow. However modern or civilized or enlightened we may consider ourselves, when we climb into a cave, we feel something primal stir within us…a handful of centuries of rationality, science and empiricism are promptly swept beneath hundreds of thousands of years of instinct and evolutionary conditioning.” And here’s the part that will particularly vex readers of this magazine:

When even the most rational, most materialist, hardest-line atheist climbs into a subterranean dark zone, you will hear them drop their voice to a whisper—somewhere in their unconscious, they feel awe and immensity and mystery, and they recognize this as a holy place.

I’ve never been in a cave, thank goodness, but I doubt that this is the case, and not just for atheists. I also think that Hunt’s passion for attributing mysticism to caves and such can end up sounding atavistic in a disquieting way. While envisioning Mayan (subterranean) sacrificial practices, he comments, “Beyond the barbaric violence of the scene…I found myself marveling at this collective ritual as a display of prodigious faith and devotion….Here was an entire civilization… [a] people who ardently believed that these hidden chambers…were sacred and magical, that they possessed the power to reshape reality.” I’m too appalled by the savage ceremony Hunt describes to marvel at it. In Underground, Hunt comes off as a civilized gentleman, but the book, unintentionally, says something alarming about the power of religiosity to lead even earnest, decent folks astray.

Hunt isn’t oblivious to the ominous fantasy phenomena that cultures have superimposed on the subsurface realm he cherishes. These subterranean dreamscapes are invariably terrifying, underworlds where evil rules and supernatural, feral creatures, such as the Australian Mondongs (“capricious spirits”) lurk (Hunt thinks he might have seen one). The author is quite right that humanity has, for millennia, perceived underground territories in such a dread manner. (For those influenced by Freud, these baleful realms can be symbols of the turbulent id.) But for contemporary society, I think these age-old nightmare notions have become obsolete, superseded by cyberspace. The malevolent corners of this new digital territory are much more horrifying than antiquated ideas about folkloric terra incognita and fiends. I don’t mean cartoonish memes like Slender Man and Momo (although even these can prompt violence). I write in the aftermath of a heinous incident in New Zealand, in which a white supremacist murdered at least fifty people and wounded fifty more at two mosques. The scum responsible for this atrocity apparently perpetrated the massacre for worldwide internet viewing. His audience was the vile bigots and sociopaths that pullulate and thrive online. That’s more frightening than Mondongs, alligators, and claustrophobia.