“America First” All over Again? Historical parallels are always prone to error and abuse,but that doesn’t mean we should stop analogizing

BEFORE STEVE BANNON was kicked out of the White House in the fall of 2017, he said he wanted the Trump presidency to be “as exciting as the 1930s.” Odious as that sounds given Bannon’s affection for intellectual fascism, it’s clear from context that isn’t what he had in mind. Rather, he was saying he wanted Donald Trump to be as active and experimental in rebuilding the nation as Franklin D. Roosevelt was in building it. To Bannon, the parallels were there: access to cheap credit, control over both chambers of Congress, a blind trust in the presidential nominee by his base, and a national sense that something must be done (without an accompanying vision of what that something was).

Of course, most political observers didn’t have Roosevelt’s New Deal in mind when they heard of Bannon’s hope. Partially it was because Trump was representing a political party that had spent the 1930s trying to block New Deal legislation—the right to collective bargaining, a minimum wage, price controls, old-age pension, progressive taxation, public management of infrastructure, financial regulation, and so on—and then spent the rest of the century dismantling the legislation that did get passed. Partially it was because while both presidents blamed “the elite” for the country’s problems, Trump’s elite was obviously very different from Roosevelt’s “economic royalists.” Roosevelt blamed the Great Depression on those who made the economic decisions of society: on who decided what wages were, what got invested in, what got built and where. Trump’s elite was much vaguer. Sometimes it meant hostile Republican donors or politicians who voted for NAFTA or the Iraq War. But mostly it seemed to be made up of middle-class liberals (who, economically speaking, have little decision-making power).

However, the most obvious reason observers didn’t think of Roosevelt when they thought of Trump was because Trump’s very campaign slogan—”America First”—was the slogan all anti-liberal, anti-Roosevelt forces rallied under in the 1930s.

For the politically uninitiated, “America

First” sounded like just another campaign slogan. A sympathetic interpretation was that both parties had for too long served the interests of a wealthy elite that prioritized capital over country. That wrote trade deals making it easier to move capital around the world and harder for national governments to improve the lives of their people. However, as many quickly noted, the slogan had a shady history, most famously remembered because of the America First Committee (AFC). Founded at Yale in September 1940, the AFC intended to be the unifying movement for stopping the United States from going to war with Germany or Japan. Non-intervention was just advertising though. Behind the America First Committee’s supposed isolationism was really just sympathy for Nazism—particularly its racist outlook and top-down way of running things.

For the politically uninitiated, “America

First” sounded like just another campaign slogan. A sympathetic interpretation was that both parties had for too long served the interests of a wealthy elite that prioritized capital over country. That wrote trade deals making it easier to move capital around the world and harder for national governments to improve the lives of their people. However, as many quickly noted, the slogan had a shady history, most famously remembered because of the America First Committee (AFC). Founded at Yale in September 1940, the AFC intended to be the unifying movement for stopping the United States from going to war with Germany or Japan. Non-intervention was just advertising though. Behind the America First Committee’s supposed isolationism was really just sympathy for Nazism—particularly its racist outlook and top-down way of running things.

Charles Lindbergh, celebrity aviator and AFC’s most popular spokesman, frequently visited Nazi Germany in the 1930s to study its aviation industry and was “impressed” with Nazism’s “organized vitality” and “convinced dictatorial direction.” By that time German Communists were already exiled or in camps, and one of Hitler’s first acts as chancellor was to destroy Germany’s trade unions. Conversely, labor militancy was at an all-time high in the United States, which terrified AFC’s central committee of corporate executives and business owners, including R. Douglas Stuart (Quaker Oats), Jay C. Hormel (Hormel Foods), Robert E. Wood (Sears, Roebuck and Company), and Henry Ford (Ford Motor Company). As historian Bradley W. Hart puts it in his recent book, Hitler’s American Friends, “America First was quite literally owned and operated by some of the country’s most powerful corporate interests.” As Dorothy Thompson (the first American journalist expelled from Nazi Germany) wrote: “Nazism, in Mr. Ford’s mind, is a Ford factory on a gigantic scale.” An impression of fascism no doubt shared by the rest of AFC’s central committee (albeit a Ford factory unencumbered by Detroit’s Unemployed Council or the United Steel Workers).

Behind the America First Committee’s supposed isolationism was really just sympathy for Nazism—particularly its racist outlook and top-down way of running things.

Just four days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, AFC disbanded. There have been attempts to rehabilitate the movement’s historical image, which is understandable given its popularity among the country’s “economic royalists” as well as how many of the country’s postwar intellectuals were sympathetic to it in their youth. In 2012 one such postwar intellectual, Gore Vidal, admitted that the movement “did attract some genuine homegrown fascists” but also said that the majority of the country was opposed to the war and that Lindbergh was “attacked as a pro-Nazi anti-Semite when he was no more than a classic Midwestern isolationist.”

But if Lindbergh wasn’t an anti-Semite, then there’s never been one. He thought all the things an anti-Semite thinks: Jews control the media; Jews are behind most political radicalism; capitalism would be more humane if it weren’t for Jewish usury; a country can only tolerate so many Jews before it collapses. Perhaps the nastiest thing Lindbergh ever mustered to say about the Nazis—who awarded him the second highest prestige medal in Germany in 1938—was that they handled their “Jewish problem” so “unreasonably.”

Vidal was right though about a majority of Americans opposing war. Contemporary polls showed that most Americans hated Nazism but didn’t want to be the ones to fight it. They were in favor of sending guns, planes, and whatever else to Britain and France—just not Americans.

Popular opposition to getting involved in another European war was easy to understand. Less than twenty years earlier, Americans were told that they were going over there to fight for democracy, motivated to enlist by horror stories of German barbarism. Shortly after the war ended—and over 100,000 Americans had died—it was revealed that many of those stories were fake or exaggerated and that the consequences of the war weren’t democracy and liberty but retribution and imperial parsimony. “From the very beginning it was a lie to say that this was a war to make the world safe for democracy,” President Warren G. Harding said in 1922. And after 1936 the results of the Nye Committee were common knowledge: financiers and arms-manufacturers had pressured the Wilson administration to intervene. Now the Roosevelt administration and the interventionists in the press were saying the same things as were said then—that Nazis were terrorizing Jews, that Nazism was a threat to democracy and “If we didn’t stop them there…”

But, the America Firsters were asking, how could anyone be sure the stories of Jewish persecution were true? And if such stories were true, they asked, who are we to say they didn’t have it coming? As Russell Kirk wrote with sarcasm to a friend, “We must crush that Hitlerian tyranny which commits such atrocious crimes as deporting Polish Jews into Eastern Poland.” Anti-Semitism was in vogue. You could get away with blaming Jews for the depravities of both capitalism and Communism. And there were plenty of newspapers comfortable with justifying fascist violence as a proportional response to Communism and labor militancy. Besides, how could anyone with a straight face say we’d be fighting a war for democracy alongside the Soviet Union and the British Empire? “Talk about freedom. What of India, what of Hong Kong?” shouted another popular AFC spokesman, Montana Democratic Senator Burton K. Wheeler, on the floor of the US Senate.

While it was advantageous for both the AFC and the Roosevelt administration to paint the movement as the face of non-interventionism—advantageous for the AFC because most Americans were opposed to war and therefore, through political osmosis they hoped, might start to agree with the AFC’s general politics; advantageous for the administration because the AFC’s stated reasons for opposing the war were full of anti-Semitic hocus-pocus—AFC was actually far from isolationist.

For example, Lindbergh wanted to convert the whole Western Hemisphere into an American imperial front, which would’ve involved quite a bit of intervening in Latin America. He also wasn’t opposed to staying out of Europe in principle. He insinuated the US should intervene if “that most priceless possession, our inheritance of European blood” was at risk either from “attack by foreign armies” or “dilution by foreign races.” He believed America’s affiliation with Europe was racial rather than ideological. Therefore, if Europeans were killing each other over ideological differences, it wasn’t the United States’ place to step in. Of course this way of thinking played right into Nazi hands. The prevailing wisdom was that Jews weren’t white, so Hitler could be excused for saving Europe from a “foreign race.” And Soviet Communism—despite Lenin being Russian and Stalin being Georgian—was, to borrow a phrase from the president of the New York Stock Exchange in 1930, an “evil disease from the Orient”; so if the Soviet Union defeated Nazi Germany that would be another pretense for a US invasion of Europe. With a bit of verbal sophistry, both Judaism and Communism were racialized. And from that Hitler’s tyranny was justified and the US was left on the sidelines of Europe unless the Red Army made it to the Rhine.

Slogans, we know, aren’t just words. They connote emotional attitudes and signify ways of thinking about the world. Barack Obama’s “Change” obviously meant change in a particular political direction, and Hillary Clinton’s “I’m with Her” was more about female political representation than it was loyalty to a particular candidate.

Such was also the case with “America First,” as University of London Professor Sarah Churchwell masterfully demonstrates in Behold America: A History of America First and the American Dream. “America First” didn’t begin with the AFC. It had been the campaign slogan of all three Republican presidents in the 1920s—Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover. Before that it was part of the campaign slogans of both Republican and Democrat candidates (Woodrow Wilson’s was just “America First” while Charles Evan Hughes’s was “America First and America Efficient”). Still, the slogan was primarily used to justify Republican politics. Harding used it to defend his agricultural tariffs. The KKK used it to defend its anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic bigotry. For them, “America First” translated to “America for Americans,” whereby “Americans” meant native-born “Nordics” (northern European Protestants). Later, a 1939 letter to the St. Louis Star-Times called for rejecting 20,000 Jewish refugees from Europe; it was signed “America First.”

What today gets called “identity politics” was, in the early twentieth century, called “hyphen politics” or “hyphenism,” which was supposedly as grave a threat to our democratic order as identity politics supposedly is today. German, Italian, and Irish immigrants were accused of refusing to “integrate,” while Democrats were accused of sowing division by pandering to ethnicity for votes. The New York Times ran articles like “Hazing the Hyphenates” and “No Room for the Hyphen.” Fuss was made about having to capitalize the “n” in “Negro,” using “Chinese” instead of “Chinaman,” and no longer being able to make jokes about the Jews. “America First” fit in as shorthand for anti-hyphenism, anti-immigration, anti-welfare, anti-Communist, and anti-labor (strikes, sit-ins, and slow-downs of course going against the “national interest” which always suspiciously aligned with that of the rich).

The founders of AFC were aware of how the slogan was used and who would be attracted to it. So to trust the AFC was ever just about non-intervention—especially considering its leaders explicitly repudiated non-intervention when it came to Latin America and repelling “alien” threats from Europe—is either naïveté or wish-fulfillment. Lawrence Dennis, a genuine isolationist who Hart calls the “intellectual face of American fascism” in the 1930s, later said of the AFC: “The anti-intervention or then so-called isolation cause was basically anti-New Deal…The America Firsters or anti-war factors were not really pacifist or anti-war. They were anti-New Deal and that made them anti-war in that period.” But the New Deal and a war against Nazism weren’t as independent as Dennis makes them sound. Both came from the same political impulse: to fight against Social Darwinism. Those who were for appeasement with Nazism abroad were often for appeasement with capitalist hierarchy at home.

Two-thirds of AFC’s 800,000 members were within 300 miles of Chicago according to Hart in Hitler’s American Friends. This was partly because of the German-American population in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Iowa and the Irish-American population in Chicago. Many Irish-Americans loathed the British and instinctively sided against them; second-generation German-Americans remembered the anti-German bigotry of World War I, and first-generation German-Americans tended to be more sympathetic to Nazism as they had fled Germany in the 1920s to escape Weimar Germany’s inflation and liberalism. The AFC concentration was also partly because of a political tradition of rural populism in the Midwest that had been anti-British and vaguely anti-Jewish for decades.

If Dennis is correct, and the AFC was more about opposing the New Deal than it was about opposing interventionism, why was its propaganda focus so much more on the war than government intervention in the economy?

“America First” and Trumpism share the same enemies: immigrants, liberals, organized workers, redistributionists, and “hyphen-Americans.” And the same desire: a world of capitalist hierarchy and social domination.

Mostly it was opportunism. The New Deal was popular and war wasn’t. An anti-New Deal movement—especially one whose leadership was made up of business owners and corporate executives—would’ve been dead on arrival. And Roosevelt was personally very popular, winning 472 of the 531 Electoral College votes in 1932 and 523 in 1936. He was the first Democratic nominee to win a majority of African-American votes. (For all the New Deal’s racist implications, such as not applying minimum wage laws to sharecropping and housework, it was still the Democratic project that won African Americans to the party because of its universal benefits.) His electoral coalition of the South and the majority of cities and industrial areas was politically fragile but electorally unbeatable. AFC’s leadership knew it couldn’t beat the New Deal head-on, but they also knew the New Deal largely depended on the tact and initiative of Roosevelt’s administration. So they accused Roosevelt of being a warmonger. Not because he opposed Nazi dictatorship but because he would use the war as a justification for his own.

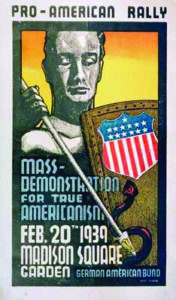

German American Bund parade on East 86th St., New York City, October 30, 1939

To a disturbing degree, the America First Committee adopted the imagery and language of American fascism. The German-American Bund—a group that promised to “save America for white-Americans” and was so pro-Nazi that the actual Nazis disavowed it—hosted a “Pro-American Rally” at Madison Square Garden in 1939 to celebrate George Washington’s birthday. The first president was idealized by American fascists because of his farewell address where he warned of “foreign entanglements” and because he was a military man who got back into politics in order to suppress internal dissent (e.g., the Whiskey Rebellion). Centered behind the rally’s speakers and among the swastikas and overtly fascist banners like “Stop Jewish persecution of Christians” was a giant portrait of Washington. Two years later, Lindbergh would stand in front of a similar portrait at AFC rallies, whistling similar praises. American fascists flocked to the movement.

Did Donald Trump know about the history of “America First” when he started using the slogan? Hart says that question has “never been sufficiently answered, but undoubtedly some in his campaign must have.” Ignorance on the part of the president is a reasonable assumption. However, there’s some evidence that suggest he wasn’t completely in the dark about its historical meaning; the first time he ever used the slogan was in describing his foreign-policy outlook to the New York Times: “I’m not isolationist, but I am ‘America First.’” Regardless, one of his political advisers—particularly one from the Buchananite wing of the Republican Party—would’ve been aware of the history.

How does the history of “America First” explain why Bannon didn’t get his wish for 1930s excitement? Why was there no higher taxation on the wealthy like he wanted? Or a trillion dollar infrastructure bill? Why has Trump’s presidency been a typically Republican one in so many respects? (Even his morally pathetic moment saying there was “blame on both sides” in Charlottesville isn’t without precedent—Eisenhower said the same thing in the 1950s between “extremists” on both sides of school segregation.)

It isn’t as if the slogan “America First” is some dark incantation against progress. But the economic forces and political impulses behind the AFC were similar to the forces and impulses behind Trumpism. The two share the same enemies: immigrants, liberals, organized workers, redistributionists, and “hyphen-Americans.” And the same desire: a world of capitalist hierarchy and social domination— as economist Lewis Corey described in 1935, a world where “the hierarchical relations of corporate industry” would be imposed “on the whole social and political life of the nation.”

“‘America First’ will be the major and overriding theme of my administration,” Donald Trump said during a foreign-policy address in April 2016. Three months later, the theme of Day 3 of the Republican National Convention was “Make America First Again.” At his inauguration, Trump declared: “From this day forward, a new vision will govern…it’s going to be only America first, America first.”

That probably isn’t what the majority rank-and-file of either the AFC or Trump’s base signed up for. But the predictions of what someone will do are better forecast by what they promise those with power than what they promise those without it. As someone once said, what a politician tells voters is what he or she says to get votes; what that politician tells donors is what he or she is going to do. Bannon wanted to make a second New Deal with the help of the party and class interests that opposed the first one. Such political idealism is a constant factor in right-wing populism—as if ideas can manifest realities on their own without real-world power; as if society isn’t a tapestry of institutional compromises but of debate points.

Historical parallels are always prone to error and abuse. They can obscure just as well as they can illuminate. A case in point: those who opposed war with Hitler no doubt thought they were sound in historical judgment when they argued that this was just World War I all over again; that the horror stories would again prove exaggerated; that once again America was being enlisted to fight for Britain’s and France’s empires.

But that doesn’t mean we should stop analogizing. Clive James wrote that history is the opposite of fanaticism. And one of the few lessons history teaches is that while things change, how we talk about them remains the same. The humanitarian justification for war, the crisis of masculinity, the panic over migration or cultural eccentricity—these things can be found in all periods and ages. The complaint that “kids are too soft these days” can be read in today’s New York Times or in the diatribes of medieval monks.

What’s striking about the AFC and the history of “America First” is not its novelty but its familiarity. Likewise with the liberal-sentimental reaction. For every “America First” ideologue who talked of racial purity and national subservience there was an enraged liberal who damned his appeals to “prejudice, ignorance, and hatred.” But it wasn’t moral censure that stopped the “America First” ethos; it was a positive political vision. A positive political vision perhaps best personified by Franklin D. Roosevelt and his so-called Brain Trust but that was felt downward by everyone from the Alabama sharecropper to the Ohio factory hand to the flesh-and-blood Rosie the Riveter in California. The best way to stop fascism was to show that democracy worked; that it could create a society with fewer weak minds, empty stomachs, or broken individuals; that freedom was not best safeguarded by brokerage with those who would gladly take it away, but by those who would gladly take it for themselves.