FIRST PERSON | Nietzsche in New Guinea

Before I converted to Christian fundamentalism as a young man, the only philosophers I recall having any familiarity with were Bertrand Russell and Immanuel Kant.

My introduction to Kant came from Ms. Emily, the librarian of Kenai Community Library. I was fourteen then and living in Kasilof, a tiny community on the Kenai Peninsula in Alaska. Ms. Emily, a tall, white-haired woman who drove an ancient but elegant white Jaguar, was an observant librarian who never pulled back from recommending books she thought might interest a reader. I can’t prove it, nor am I certain of the chronology, but I’m pretty sure she’d seen me read a spate of books related to the Holocaust. I recall her recommending Treblinka, by Jean-Francois Steiner, and us talking about it after I completed reading it.

Whatever the case may have been, I found Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason entirely too cumbersome for my adolescent mind. Russell’s Why I Am Not a Christian, however, was much more readable and met the moment’s need, as I was being evangelized by two classmates.

So, Russell and Kant. Those were the two philosophers I had some familiarity with before becoming a devout fundamentalist.

Almost right after my conversion, I found myself experiencing severe doubts about what I’d done and why. Looking back with the cold eye of honesty, I believe I only barely trusted in Jesus in order to woo and marry a fellow college student who was a conservative, Bible-believing Christian. (I believed I’d find companionship and sex and got little of either, but that’s another story.)

My doubts drove me deep into the writings of Christian apologists. Through the books of the Christian philosopher Francis Schaeffer and the apologist Norman Geisler, I became aware of many other philosophers. When reading their books, I became familiar with words and concepts like epistemology, ontology, a posteriori, Helenization, the law of noncontradiction, and the excluded middle.

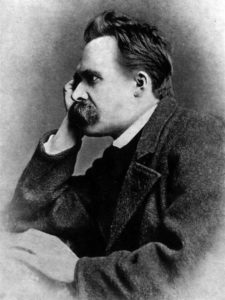

I also, of course, became aware of the bogeyman of all philosophers: Frederick Nietzsche. Most all the Christian apologists, apart from bringing up Nietzsche’s “God is dead” declarations, spilt most of their ink making the distasteful, nausea-inducing connection between Adolf Hitler and Nietzsche.

As with all my religious peers, I failed to actually read Nietzsche. Fact is, and to my shame, for many, many years I failed to read anything other than material written by conservative Christian authors. Until I hit the wall of doubt-fueled despair. At the time, I was working as a fundamentalist missionary in the high mountain jungles of Papua New Guinea. I’d been there for several years and had experienced zero success in evangelizing a single soul. I wanted to give up.

During that time of darkness in the very core of my being, I came upon a book by the prolific and recently deceased Christian writer Eugene Peterson. He is most well-known for his paraphrase of the New Testament called The Message. Among his devotional commentaries is his book on the Psalms of Ascent that were sung or chanted by pilgrims going to Jerusalem (Psalms 120–134). He titled this book A Long Obedience in the Same Direction.

Right away, I was drawn by the title. It was becoming evident that my ministry, as well as my life as a devout Christian, demanded a long obedience in the same direction.

As a sort of mantra, I began going about my days quietly chanting to myself “long obedience, long obedience, long obedience.” I awoke to repeat those words to myself, frequently ending with “Please, Lord, please!” Throughout the day I repeated the words and usually fell asleep with them on my mind.

For a year or so after reading Eugene Peterson’s book, I maintained my long obedience in the same direction. And then slowly, without deliberation, I stopped the chant. Instead, I silently drudged through each day.

One night I was watching The Wizard of Oz with my children, and when the Cowardly Lion, the Scarecrow, and the Tin Man hide behind a wall watching the Wicked Witch of the West’s soldiers march into their castle, I found myself emotionally connecting with their marching chant:

“O—Ee—Yah!

Eoh—Ah!

O—Ee—Yah!

Eoh—Ah!”

For days after that, I caught myself chanting along with the guards of the Wicked Witch of the West. As I am wont to do when faced with depression, I return to books that seemed to help. In this case, I returned to Eugene Peterson’s book, and lo and behold, that is when I noticed that the title came from Frederick Nietzsche. I recall standing at my bookshelf and gasping when I realized that.

As I said earlier, Nietzsche is a major bogeyman for fundamentalist Christians who know anything about him. They not only think of him as the father of atheism (which, of course, Nietzsche’s not), but also as the supreme influence upon Hitler for the Holocaust (which he wasn’t.) Looking to Nietzsche for encouragement was on par with asking Satan to answer your prayers, so I put Peterson’s book back on the shelf and sought encouragement in some other book.

But here’s the thing, I really respected Peterson. I also had, by that point in my reading career, taken to reading first sources when I read a quote that moved me. Long story short, I got hold of a copy of the Modern Library’s The Philosophy of Nietzsche and read it cover to cover.

Reading Nietzsche in New Guinea changed my life.

I expected to read the words of a rabid atheist, the sort you’d expect from one of Hitler’s henchmen. I expected harsh, guttural words. Instead I got: “When Zarathustra was thirty years old, he left his home and the lake of his home, and went into the mountains.” These are the first words of Nietzsche in the Modern Library, which as can readily be surmised, begins with Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra. I was reading them from the New Guinea mountain upon which we lived at an elevation of 6,300 feet above sea level.

Three pages later I found myself laughing and crying when I read:

“And what doeth the saint in the forest?” asked Zarathustra.

The saint answered: “I make hymns and sing them; and in making hymns I laugh and weep and mumble: thus do I praise God. With singing, weeping, laughing, and mumbling do I praise the God who is my God.”

That was exactly how I felt! My barely tenable faith had been reduced to so much mumbling and weeping, punctuated by singing and laughing. I devoured Nietzsche. His beautiful writing frequently moved me to tears.

In my self-aware lack of training in philosophy, I doubted myself when I felt some of his arguments lacked cogency. In fact, there were times I wondered if he had mental health issues. (This is an area I have some familiarity with; depression, bipolar disorder, and very likely schizophrenia are replete on the maternal side of my heritage.) Later, as I became increasingly taken by Nietzsche’s writings, I read biographies on him and learned that he was a “PK” (preacher’s kid) and that he indeed had mental health issues (although just what those were remain uncertain even as recent as Sue Prideaux’s lovely biography, I Am Dynamite: A Life of Nietzsche (2018).

Reading Nietzsche led me to read more and more first sources, ranging from learning enough Greek to work through portions of the Greek New Testament to reading Plato and Aristotle. (Aristotle said: Men create gods in their own image. This didn’t make him an atheist, but it sure made it easy to see him as one if one wanted to.) I reread Bertrand Russell and some of Paul Kurtz (who I’d read while a student at Florida Bible College) while rethinking some of the arguments for the existence of God. Today, I am an atheist as well as a skeptic.

After nearly twenty years in the ministry, I went into maintenance work. Frequently, when I assess a task, my co-workers or boss will ask how certain I am regarding the solution of said task at hand. My answer almost always is prefaced with, “The only thing I’m completely certain of is that all triangles have three sides.” Then I’ll give an off-the-cuff percentage of how likely I am that my assessment is correct.

As with Nietzsche, who sometimes referred to himself as “the philosopher of perhaps,” I’m no longer drawn to certainty. I’m drawn to patterns and kindness. And although I cannot contribute all of how I think today to Nietzsche, it’s no exaggeration to say that had I not read him and had I not followed the path of curiosity such reading led me to, I would be an unhappy person today. Instead, I find myself content with uncertainty and glad to be free of the burden of religion.