The Accidental Atheist: From Hippie to Humanist in Half a Century

I was born eight months after my parents were married in 1931 and from there my life has been one accident after another. My identity was forged in part by my father, who both told a lot of stories about, and always seemed to relate to, the underdog. My mother worked to keep my brother and me in Lincoln Grammar School and out of reform school, which was a full-time job in those days. As I often describe it, although we weren’t poor, I never slept alone until I was married.

After childhood I became an accidental scholar. I scored 800 on the math SAT, and somebody decided I ought to be an engineer. So I went to MIT and promptly flunked out by Christmas of my freshman year. In fact, I was the first president of the freshman class who ever flunked out. I returned, however, to avoid going to Korea. Most of my relatives came from Germany, and we have a long history of cowardice that stems back to Bismarck in 1893. They would emigrate whenever there was a major war, and I didn’t want to spoil the Starks’ record. So, I ran back to MIT in June of 1950 to stay out of the war and stay in ROTC.

I then became an accidental pedagogue. MIT had, until 1953, an unblemished and perfect record of placement of its graduates. Lo and behold, here came Stark, limping along with a marginal record and no offers. So MIT and I decided on an arrangement whereby I could be a teaching assistant in the Sloan School of Management. I could work for a year for $300 a month, teaching two courses and taking two. That was the agreement. At the end of the year I would get a recommendation to any graduate school I chose, except MIT.

Next I became an accidental warrior. I had to serve my time in the U.S. Air Force and was transferred back to my hometown of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. After finishing my active duty, I decided to go on to graduate school. Berkeley didn’t know any better and admitted me.

At the University of California, Berkeley, I became an accidental hippie.

At the University of California, Berkeley, I became an accidental hippie.

Becoming a banker, however, was no accident. As a child I can remember taking Kuder Vocational Preference tests where you pushed a little pen through one of a group of choices such as, “Would you rather chop wood, read a book, or play the piano?” And then they scored it for you and said, “Well, you ought to be a scientist,” or “You ought to be a social worker,” or any number of professions. I always came out a social worker. However in our town of Wauwatosa, the guy who was the secretary of the YMCA drove a Model A, and the guy two blocks down was a banker and he drove a Buick. It didn’t take a young kid very long to figure out which way he or she was going to go. I decided way back then I was going to be a banker. As a matter of fact, I wanted to be the president of a bank. So it’s no accident at all that I became just that.

I didn’t want to go through all the usual requirements of learning to be a teller, a vice president, and all those other jobs along the way. So I started my own bank and that way I could start right at the top, which I like doing.

Returning to accidents, I then became an accidental religious leader. We had a fellowship, as Unitarians do, in Walnut Creek, California. We raised a little money and hired a minister, Aron Gilmartin, who was a great guy. One day he asked if I would like to help out a little school in Berkeley called the Starr King School for the Ministry, which was a Unitarian seminary. They owned their own building, had a $30,000 endowment, two faculty, and eight students, and they were going broke. When I arrived there they asked, “Will you be the treasurer?” I said yes. “Well, then you have got to be on the board of trustees,” they urged. “Can you come to the first meeting?” At that first meeting they put my name in nomination to be chairman of the board. And I knew I was being set up, but I became the chairman, a position I held for ten years and which exposed me to some of the most interesting people I have ever known.

And then I became an accidental Democrat.

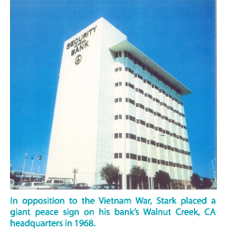

I opposed the Vietnam War in the 1960s so when Eugene McCarthy came along I said, “That’s my guy.” I’d been what you might call a La Follette Republican when I moved from Wisconsin to California. But then, when I was working for McCarthy, somebody said, “If you want to be a delegate, you’ve got to be a Democrat.” So I went down and changed my registration and the rest is history.

In 1972 I thought I could be Secretary of Health and Human Services under George McGovern. When it became apparent that wasn’t likely, I became an accidental congressman. I was sitting in my office one day when a group came in and asked if I would like to run in the primary against a senior incumbent Democratic congressman who was for the war, said there were no hungry people in our district, and didn’t think the environment was in any danger. These folks wanted somebody to challenge him in the primary. I did, and I won. I went to Congress in 1972 and, again, the rest is history.

The next accident made me a health care expert in 1984. Every two years Congress reorganizes itself and in our committees we select subcommittee chairs by virtue of their seniority. Earlier I had chaired what we called the Welfare Subcommittee on the Ways and Means Committee. We dealt with aid for dependent children and a whole host of programs that I still work on diligently, as does my wife, Deborah Stark. Then from 1981-1984 I chaired what we called the “Teeny Tax Committee,” rewriting the Life Insurance Tax Code (for any of you who want to fall asleep some night, read the Life Insurance Tax Code).

In 1984, Rep. Jake Pickle (D-TX) opted for my committee. I was left with the choice of Social Security or Health. I took health, never having served there before. I became Chairman of the Subcommittee on Health on a Tuesday. By Thursday I learned about six organs in my body that I didn’t know existed. Each one had a lobbyist in Washington representing it and Humana offered to transplant any of them for free, and there I was.

My most recent accident was becoming a well-known humanist. Somewhere along the line a nice group of people, the Secular Coalition for America, sent a form requesting information from those of us who support separation of church and state. In response to a question about belief you could check one of three boxes. I checked the one that said I didn’t believe in a supreme being. Then there was a blank to answer the question, “What religion do you associate with?” I wrote, “Unitarian” and sent it back to them. (What I didn’t know is that there was a reward offered to find high-ranking nontheist politicians and that some guy out in Hayward, California, was hustling to make $1,000 by turning me in. I met him later at one of my town hall meetings, and he wouldn’t share the money with me. I told him, “That’s not fair!”)

My most recent accident was becoming a well-known humanist. Somewhere along the line a nice group of people, the Secular Coalition for America, sent a form requesting information from those of us who support separation of church and state. In response to a question about belief you could check one of three boxes. I checked the one that said I didn’t believe in a supreme being. Then there was a blank to answer the question, “What religion do you associate with?” I wrote, “Unitarian” and sent it back to them. (What I didn’t know is that there was a reward offered to find high-ranking nontheist politicians and that some guy out in Hayward, California, was hustling to make $1,000 by turning me in. I met him later at one of my town hall meetings, and he wouldn’t share the money with me. I told him, “That’s not fair!”)

Within a week of the SCA’s announcement of my response, I received over 5,000 emails from around the world, 4,900 of them congratulating me and all mistakenly saying it was an act of courage. It wasn’t–it did not take any courage at all. I just filled out the form. I did hear from a few people who disagreed. Now, having been in this business as long as I have, I’ve got a collection of lipstick-written letters calling me names that I can’t even mention in liberal mixed company. But the 100 or 150 negative responses that I got were the sweetest, kindest remarks. They would say, “We hope you are happy. Is there anything we could do to help you?” I have never been criticized in a more generous way and I said, “I like this business.” I mean, if that’s as tough as the critics get then what a great decision I made.

I think that humanists are on the cusp of a movement, and I would like to offer some suggestions about how it could be expanded to help those of us who have progressive interests in the world. But first I want to suggest what little I have learned about God and governments.

I think that most of my colleagues, and politicians in general, just pay lip service to one god or another. Go back in history–was Caesar placating gods or was he chasing after Cleopatra? Was Napoleon more concerned with the pope or the Prussians? Did Hirohito really think he was a god? Did he need Hitler or did he need oil? The answer is that it has never been about God for politicians. It has been about power. It has never been about peace on Earth. It has been about profit in your pocket.

We have a president who, commendably, put his alcoholism under control without treatment. And I say this in all sincerity because beating or controlling alcoholism by oneself is a monumental task. So, we could say it’s understandable that under those circumstances George W. Bush felt he was born again. (And if the Supreme Court made me president, I might think I’d received a message from God.) But I think it’s this sense, misguided or not, that has gotten this country into war, brought economic problems, denied our children education, denied 47 million people decent health care, and has led the United States into an economic disaster. We are in a recession, and only the very poorest among us realize the true magnitude of that recession. I think we have to look to this person who has thought more about good and evil than about what we ought to be doing for the population at large.

If we can empower the least powerful among us, we’ll be on our way. I would confine God to currency, constitutional control, and colloquialisms like “Godspeed” and “gadzooks.” Then we can begin to deal with the real problems in the world, such as those related to education, health care, poverty, and human rights. But we can’t move ahead if we’re going to tolerate abstinence-only training, creationism, denial of environmental destruction, and oppression of reason. The power of simple solutions can fill a vacuum caused by the abandonment of reason, and that has got to end.

We recently marked the fortieth anniversary of the tragedy that befell Bobby Kennedy. I can remember making speeches all those years ago, when I was still a banker, about corporate responsibility. I quoted Kennedy who wrote that one of the dangers for all of us who enjoy the educational and economic benefits of the middle class is that we may be unwilling to risk the comfort we have in our lives in order to help others. For those of you who are, each day, risking that comfort, you’ve got to continue to do it. When you make a little change in things, it reverberates through the system.

We tried to do it in the banking business and you know what? It was easy. First, we provided daycare. Then we provided transportation for our minority employees who we trained in our Oakland office, and who couldn’t move out to the white suburbs. Even though we would promote them, there was no place for them to live. No black church to go to. So they rode in our bus or our shuttle to any of our branches in the suburbs and came home so they had the same eight hours. And they were then allowed to apply for promotions or openings in other branches. We had some of the most dedicated and loyal employees.

And we did other things. We told people that Series E bonds were a rip-off, and the Treasury revoked my right to sell E bonds. So we sold our own E bonds for the environment and got a lot of publicity and new customers. It’s not hard to attract people. And I want to suggest to this group that the Internet is now the way to do it. All you have to do is look and see the way Barack Obama has communicated in his presidential campaign. I haven’t seen as many young people involved in politics since George McGovern ran in 1972. And if there are 8,000 people in the American Humanist Association, you can become 800,000 people by this means of communication.

Ultimately, for those of us who believe in a human destiny, the legal system and its courts remain our best avenue for change. But in terms of getting your message across, I would also suggest, when all else fails, to try a little ridicule. After all, how do you reason with Frank Morgan when he is behind the wizard screen? Think of Cyrano who used his wit as a rapier. And John Kenneth Galbraith’s quote: “The modern conservative is engaged in one of man’s oldest exercises in moral philosophy; that is, the search for a superior moral justification for selfishness.”

But regardless of our manner we must always stick to the truth. Which is all I did on that form I filled out last year. I’m glad I did it, and I also hope that I can somehow find a way to be more significant for the humanist movement. I want to thank you for keeping after my colleagues. We can change their minds. They don’t have to change their religion or their public statements, but we can push them to do what is right. That’s the right thing for us to do, and I applaud the efforts of humanists to affirm the dignity of each human being, (accident-prone or not).