A Confraternity of the Fatherless

Rebecca Goldstein is a philosopher and acclaimed author whose books include the novels The Mind-Body Problem, The Dark Sister, and her latest, 36 Arguments for the Existence of God: A Work of Fiction, along with biographical studies of Kurt Gödel and Baruch Spinoza. In addition to numerous writing awards, she’s received the MacArthur “Genius award,” a Guggenheim fellowship, and a fellowship at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. She is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and in 2008 was designated a Humanist Laureate by the International Academy of Humanism. Goldstein was named the 2011 Humanist of the Year by the American Humanist Association and accepted the award at the AHA’s 70th annual conference in Boston, Massachusetts, on April 8, 2011. The award was presented to Goldstein by her husband, Steven Pinker (2006 Humanist of the Year) who, in his introduction, praised Goldstein for “revolutionizing the ‘novel of ideas.’” The following is adapted from her speech in acceptance of the award.

Thank you so much. That was certainly the best introduction I’ve ever received. And Steve is right that of all the awards I’ve received this is certainly the sweetest.

I grew up in an Orthodox Jewish community where the whole idea of a girl with intellectual ambitions was beyond the pale. The highest ambition a girl like me was permitted to have was to marry early and have as many children as possible. So, I had to find my own guidance, and this depended primarily on reading. But it also depended on finding intellectual heroes for myself: people whose specific ideas inspired me and whose arguments I found clear, beautiful, and elegant, but also whose lives and the role ideas played in their lives were inspiring and provided a model for how I might live my own life.

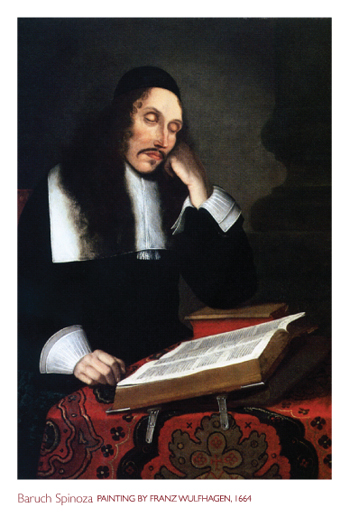

Unfortunately, most of my intellectual heroes were dead white males: Baruch Spinoza, David Hume, Charles Darwin, William James, Albert Einstein, and Bertrand Russell. But very fortunately for me, one of my intellectual heroes—he’s also a white male but very much alive—is the man who introduced me, Harvard Psychology Professor Steven Pinker.

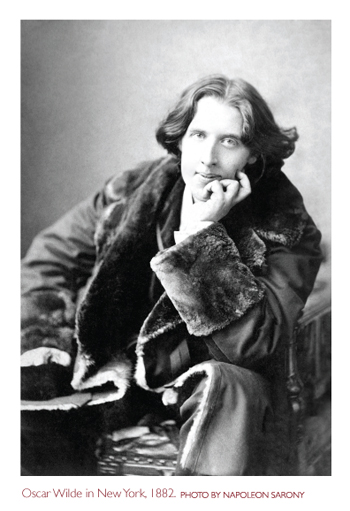

We’re very lucky, those of us who are associated with Harvard. The school has a humanist chaplaincy whose chaplain, Greg Epstein, has done an extraordinary job. I was dubious initially, but he’s created a vibrant, intellectual, ethical, and spiritual community of secular humanists there. And every year the Humanist Chaplaincy at Harvard gives out a lifetime achievement award. This year it was given to the actor Stephen Fry. I didn’t actually know who Stephen Fry was by name, but when I met him I said, “my gosh, you’re Oscar Wilde!” (If you haven’t seen Stephen Fry in the film, Wilde, you should.) And then, in his wonderful acceptance speech at Harvard’s Memorial Chapel, Fry quoted and impersonated Wilde a great deal, so much so that I immediately went back and started to reread some Oscar Wilde, including De Profundis.

Written in 1897 and published in 1905, De Profundis is of course the tragic letter that Wilde writes to Lord Alfred Douglas from his jail cell, where he had been committed for the crime of being gay. His body and his spirit are being broken down by hard labor and heartache, by the wracking realization of his betrayal by both his lover and his society. In the midst of his eloquent anguish, the following passage comes across so movingly:

Written in 1897 and published in 1905, De Profundis is of course the tragic letter that Wilde writes to Lord Alfred Douglas from his jail cell, where he had been committed for the crime of being gay. His body and his spirit are being broken down by hard labor and heartache, by the wracking realization of his betrayal by both his lover and his society. In the midst of his eloquent anguish, the following passage comes across so movingly:

When I think about religion at all, I feel as if I would like to found an order for those who cannot believe: the Confraternity of the Fatherless one might call it, where on an altar, on which no taper burned, a priest, in whose heart peace had no dwelling, might celebrate with unblessed bread and a chalice empty of wine.

When I think about religion at all, I feel as if I would like to found an order for those who cannot believe: the Confraternity of the Fatherless one might call it, where on an altar, on which no taper burned, a priest, in whose heart peace had no dwelling, might celebrate with unblessed bread and a chalice empty of wine.

And as I look around, I feel like we are a realization of poor Oscar Wilde’s wistful fantasy—this order of those who can’t believe, the Confraternity of the Fatherless. And I wonder about the ambiguity of this phrase, “can’t believe.” Is this inability to believe an incapacity or is it an endowment? Is it a sign of failure or is it a sign of strength?

When you’re brought up as I was in a very, very religious household, you’re made to feel as if your inability to believe all the things that those around you believe is a lack in you. You’re made to feel that it’s not just a cognitive failure but a moral failing. And you feel this very strongly, and you try to work to become like those whom you love—your family, your community. You try to believe in things for which there is no evidence at all, or even for which there is evidence to the contrary. Meanwhile the people around you are always encouraging you in your efforts to overcome your inability to believe. They may even be praying for you, in a loving way, struggling to retain their love for you despite the moral flaws revealed in your inability to believe and the great gap that opens up between you and them, between the way you experience the world and the way they do.

Epistemology is the branch of knowledge that studies knowledge itself. What is it, knowledge? What is the difference between knowledge and mere belief? What kind of evidence do you have to have in order to really know something as opposed to merely believing it? Even if some proposition is true, if you just happen to believe it for bad reasons, this doesn’t count as knowledge. So then, what count as good reasons for believing? These are the most fundamental of epistemological questions, and the epistemological questions are the most fundamental in philosophy. There’s a kind of ethics to epistemology, a morality in taking the grounds for beliefs so seriously, and in realizing the moral responsibilities that are entailed in our acts or beliefs. This epistemological morality gets twisted around in the context of religion, where the very groundlessness of a belief is seen as a moral strength. It’s the groundlessness of the belief that leaves you free to believe on faith, and faith is reckoned a moral triumph. This is a strange transposition of the ethics of belief.

My doubt in the propositions of my community’s faith started very early, as did the efforts to overcome the doubts. It wasn’t until I read Bertrand Russell’s Why I am not a Christian, an oddly relevant essay for a little Jewish girl to read, that I came to realize that there’s no triumph to believing on the basis of bad grounds. Bad grounds are bad grounds—there’s nothing heroic about believing when you don’t have good reasons. Quite the contrary, the heroism lies in demanding good grounds for belief, those that will stand up even when you extract the purely emotional, subjective, and biased elements. I think Wilde’s words are telling us this, that there’s a kind of heroism in heresy. That it’s an achievement, this inability to believe. We who can’t believe should feel no shame in this. Those who would urge shame on the intellectually honest and objective have got it entirely backward.

The wonderful thing is that there is a kind of confraternity, just as Wilde longed for from the loneliness of his cell. If you actually do escape from beliefs that you inherit just because of the particular group into which you happen to have been born, there’s a sweetness of unanimity that is your reward. Because all people who are trying to move away from the beliefs into which they were born and are struggling toward objectivity or rationality are moving in the same direction. And it is extraordinarily moving to me, having grown up in such an insular community, to meet people who come from traditions and from groups that are so dissimilar from mine, and we have a unity of mind because we’ve embraced objectivity, we’ve embraced reason. And this of course was the dream of another great hero of mine, Baruch Spinoza.

Spinoza pre-dates the European Enlightenment by about a hundred years but his ideas radicalized Europe and seeded the Enlightenment. It took a long time for Europe to finally catch up with this heretical, excommunicated Jew, and indeed we’re still catching up.

Spinoza pre-dates the European Enlightenment by about a hundred years but his ideas radicalized Europe and seeded the Enlightenment. It took a long time for Europe to finally catch up with this heretical, excommunicated Jew, and indeed we’re still catching up.

Spinoza was a radical secularist before the word secularism even existed. It was his hope that we would be able to detach from the irrational views into which we’re born and that we embrace simply out of loyalty to our group. It was his hope that we would be able to detach from points of view that aggrandize our position in the world and offer us the false consolation that we’re lucky enough to be in this right group and therefore eligible for God’s special favors. It was Spinoza’s great hope that as we struggle for objectivity, we would all be reaching the same sorts of beliefs and that there would be a sense of mutual understanding among us. As such, Spinoza didn’t think his particular identity as a Jew was important—he didn’t think that any of the identities that we inherit are important. What matters are the ideas that we struggle to ground, and to the extent that we do, we share one another’s minds. In other words, to the extent that we’re rational, we all share exactly the same identity.

Spinoza’s ideas were so radical that he got nothing but trouble for the troubles he took in developing them. He was excommunicated at the age of twenty-four—we still don’t know exactly why—whereupon every curse in the good book was thrown at him: “Cursed be he by day and cursed be he by night; cursed be he when he lies down and cursed be he when he rises up. Cursed be he when he goes out and cursed be he when he comes in.” It went on and on. Spinoza was smart enough not to show up for his own excommunication ceremony.

Excommunication was a form of societal control, and the particular community of exiles Spinoza was part of was a troubled and traumatized one, consisting as it did of refugees from the Spanish and Portuguese inquisitions. They were returnees to Judaism who’d been forced to convert to Catholicism at the end of the fifteenth century. Quite often, excommunication was only a temporary thing. One was excommunicated sometimes for a day, sometimes for a few weeks. If it was a really serious infraction, the excommunication would last for a year or two. But once penance had been done, one was welcomed back into the fold. In fact, one of Spinoza’s contemporaries was excommunicated twice and welcomed back as many times. Spinoza is the only one on record to be excommunicated with no chance of reconciliation. And as far as we know, he never looked back. The story goes that when the news of his excommunication reached him, Spinoza said, “I wouldn’t have had the courage to do this on my own but since they throw me out, I go happily.”

I first learned about Spinoza when I was around fourteen. At the ultra-religious all-girls school I attended we had to wear skirts down to our ankles and sleeves down to our wrists. We were not encouraged to go on to college. It was at this insular school that I first heard the name of Spinoza in a Jewish history class while we were studying the era known as Modernity. My school was, of course, against modernity. Basically the idea was that everything started to go wrong after Babylonia. And as a kind of cautionary tale, the teacher mentioned this boy who’d been born, as we all had been in that school, into a good Jewish family. His family had suffered trauma as a result of being Jewish—just as so many of our families had during the Holocaust. And the teacher told the story of this bad boy, Baruch Spinoza, who, after his excommunication, changed his name to Benedictus. Baruch means blessed in Hebrew and, of course, Benedictus means blessed in Latin.

I remember the teacher telling us that this bad boy said the most outrageous things, and how after the Jews had put him into cherem, which is the word for Jewish excommunication, the Christians all damned him and he was vilified throughout Europe, which is all true. She remarked what a disgrace it was for the Jews that even Christians damned his name. And he said such stupid things, she contended. He said that nature is God and that the Torah, the five books of Moses, weren’t written by Moses but by many authors. Indeed, it can be said (though this wasn’t said by my teacher) that Spinoza, much to his credit, founded modern biblical criticism. He was the one who first looked at the internal contradictions of the ancient Hebrew Bible and at the different authors of the five books of Moses, claiming that there were at least four different authors and that whoever compiled it, probably Ezra, lived in the Second Temple period.

So here was my teacher talking about this “stupid boy” who didn’t believe the Torah was divinely inspired and I asked her, “What did Spinoza mean that nature is God?” She looked at me very suspiciously. No doubt it was the first time I had ever asked a question in class, ever shown any interest. And I pressed her, “what does he mean by nature—flowers and trees? Does he mean physics and chemistry and biology? What does he mean?” She didn’t like where these questions were going at all and I got put in my place.

Only I didn’t stay there. And when I eventually found my way to Bertrand Russell’s A History of Western Philosophy, I was excited to read about this bad boy my teacher had mocked, to learn that a person like Bertrand Russell praised him as the noblest of the West’s philosophers. So, yes, he is somebody who had a huge influence on my life. And that’s not so very important—what’s important is that he’s been a huge influence on many people’s lives, even while many were denouncing him. Actually, to become a professor or a clergy member in Europe even a hundred years following Spinoza’s death, you had to have your denunciation of him ready. That was part of the oral exam, knowing where he’d made his mistakes. And this meant that everyone was reading Spinoza; they had to read him in order to denounce him, so he was radicalizing Europe, and in about a hundred years they were ready for the Enlightenment (which is still ongoing, and our work is cut out for us, quite clearly).

And there is still a way that Spinoza can offer us his help in the ongoing work of the Enlightenment. What Spinoza teaches us—as humanists, as those who seek our comfort and our meaning in the Confraternity of the Fatherless— is that we can’t confine ourselves to the negative. The reason that Spinoza was so dangerous to the spirit of religion, the reason that he was denounced over and over again well into the Age of Enlightenment, with Kant having to defend himself against charges of being a closet Spinozan—the reason Spinoza was seen as so dangerous is that he was so positive. In his magnum opus, The Ethics, he certainly argues that there is no room in an enlightened vision of the world for the notion of a transcendent God. But the most important thing he does is demonstrate that we don’t need God in order to ground morality. He derives morality from human nature itself. And it’s a grand and inspiring vision of the largest kind of life that we can live. A life that is completely secular, that is transcendent because it’s secular. And I think this positive vision is something that we still have to learn from Spinoza.

One often hears that we need God in order to be good, in order to ground morality or in any case in order to enforce morality. What reason could one have for being good, the thinking goes, if there isn’t the great police officer upstairs ready to give you a summons? Spinoza demonstrates a grand and high-minded, noble and transcendent view of how we can live our lives on purely secular grounds. And that’s why he was so despised, why he was so feared, why he had to be condemned, why he was called Satan’s emissary on earth, why his Theological-Political Treatise was described over and over again as a book forged in hell. Other great philosophers said things just as radical—David Hume’s beautifully reasoned argument against miracles, for example, or against arguments for the existence of God. But what Spinoza does is not just argue against the rationality of beliefs that anchor a religious point of view. He also inspires us with a secular point of view. He inspires us with a secular vision.

So there is, as Wilde wrote in his jail cell, a Confraternity of the Fatherless, and there is a kind of ethics in hardcore rational epistemology, in demanding good grounds for one’s beliefs, and holding one’s beliefs to high standards. There’s also an ethical vision that comes out of the recognition that we are fatherless, and in accepting responsibility for the world’s ills. There is no ultimate, supernatural force that’s going to right the wrongs. We have to do it for one another. We’re all in this Confraternity of the Fatherless together, which places tremendous responsibilities on us. It demands that we be grown-ups. To me, that is what the American Humanist Association and like-minded organizations are all about. It’s what being a humanist is all about. It is the vision that people like Spinoza and Wilde dreamed of, and now it’s ours. Let’s make the most of it.