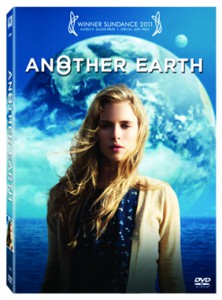

Another Earth

Most people have a mistake in life they would like forgiven: a petty theft, cheating on a lover, a lie that sprawled and webbed like a net forever hovering nearby.

For Rhoda, the main character of the movie, Another Earth, that mistake costs lives. Out celebrating her acceptance to MIT, she drives drunk. Distracted by the radio announcement of a newly discovered planet in the sky, she plows into another car, killing a pregnant woman and her young son, and putting the woman’s husband into a coma. At the age of seventeen Rhoda goes to prison and, after her release four years later, attempts to set things right.

Perhaps you missed Another Earth, which opened on only four screens after its January 2011 premiere at the Sundance Film Festival, landing on DVD about a year later. If so, you missed one of the most quietly powerful films in recent years on forgiveness and humanity. It received some critical acclaim, along with discouraging reviews like the New Yorker’s (offering left-handed compliments like “Mike Cahill’s grave, ambitious and sometimes ridiculous film…” and the more obtuse “Anyone who can explain the final shot deserves a refund.”)

Another Earth deserves another chance, especially for readers, writers, and dreamers—bonus if you’re all three. The film offers up a wholly unique look at reconciliation, with related lessons we can absorb about the art of storytelling.

The science fiction discovery of Earth 2, which may be a parallel planet to our Earth, is carefully rendered and imaginable, even if we aren’t privy to the scientific details. That hardly seems to be the point, as the film delivers a fresh look at a frequent human longing: what if we had another opportunity at life? What if we existed elsewhere to carry out that life? The bigger issue at hand is, of course, forgiveness. Not only the desire for a clean slate, but the go-ahead to put the eraser to the board.

When Rhoda is released from prison, she attempts to make amends to John, the talented composer whose life she destroyed. She arrives at his house planning to make an apologetic speech, and instead grows flustered: she claims to be from a cleaning service and offers him a free trial. Rhoda is hired and the two slowly warm to one another, though only Rhoda knows of their true connection. As their relationship deepens, she grapples with how to go about not only apologizing but asking for forgiveness.

In our modern world, everyone enjoys a good apology. Name your recent scandal, and there’s a PR firm standing behind the accused, urging public contrition. Demoralized presidents and candidates, drug-addled celebrities, the secret lives of our sports heroes—so focused are we on extracting an “I’m sorry” that we fail to consider our role in the matter. Do we forgive, wholly and unconditionally? Or do we simply nod and let the scandal fade into the background? Less sexy than the circumstances that warranted it, the emphasis on what it takes to forgive and be forgiven rarely gains our attention.

Raised in Catholicism, I practiced for the sacrament of reconciliation in school. My classmates and I rehearsed what we would say to the priest and how the priest might respond. The mantra, Forgive me Father, for I have sinned still echoes in my thoughts, though it’s been many years since I’ve visited the confessional. Those times I was forced to go as a child, my mind usually went blank. Sometimes I didn’t know what to confess. I made things up: fictitious names I called my sister, egregious attitude and backtalk toward my parents (which happened, yes, though perhaps not that same week, or with such dramatic detail.)

This is a natural tendency in human behavior: making up a story to compensate for what isn’t understood. Narrative fills in the gaps of our knowledge, teaching us to write not only what we know, as the adage goes, but also what we want to know. About life on other planets, say, or about what it takes to forgive and be forgiven. These things are not so different from the difficult task of trying to understand another human being: we are planets unto ourselves. To paraphrase Walt Whitman, we contain multitudes. Maybe even whole universes.

Space travel in the 1960s launched a now-familiar obsession in film, books, and television to know what was “out there.” Mirroring that is the human desire to understand what is “in here,” making up our core selves. Such is the conflict with storytelling, whether on a page or a screen: resolving the inner and outer worlds, who characters are, and how they live in the world. The interior versus exterior conflict is one of the greatest a fiction writer will deal with, made more intense by the simple human desire that we crave resolution: an exhalation or catharsis that all is right with the world. It could even be an emetic, as Ray Bradbury puts it in Zen in the Art of Writing: “(Intellectuals) have forgotten, if they ever knew, the ancient knowledge that only by being truly sick can one regain health. Even beasts know when it is good and proper to throw up.”

But how to achieve that moment of purge and relief? Metaphorically speaking, of course (at the theater, the answer is large candy, bucket of popcorn, and a bucket of soda). And, importantly, how to depict it? In film, resolution often arrives too quickly, too neatly, too perfectly. The deformed creature removes his mask and reveals a prince. The ugly duckling gets a makeover, becomes insufferable, then learns the value of true friendship (cue friendly dance sequence). Some wronged party is vindicated by the romantic failure of a transgressor, who is later invited to the wedding, and we all have a laugh when the family dog eats the toppled wedding cake. Choose your own details: it’s like Mad Libs for plotting.

Rarely does a film explore messier resolutions or how one goes about forgiveness. Examples from recent memory—movies such as In the Bedroom (2001) and Rachel Getting Married (2008)—come close, but lack that emetic Bradbury talks about. The filmmakers chose to leave viewers to deal with the mess of grief and emotion on their own. After seeing each one, I left the theater feeling emotionally queasy.

Another Earth gets closer and closer. The second planet looms large over our own, day and night. It is above Rhoda, tangential to her, as she trudges in a jumpsuit and hoodie to the high school where she now works as a janitor. It tags along like a shadow, and she gazes directly at the twin planet at every opportunity, going so far as to enter an essay contest to win a trip there.

We could say Earth 2 is her conscience. It reminds her of who she was and who she could have been if the accident hadn’t happened, along with the woman, child, and baby-to-be who no longer are. Do they still exist, elsewhere? Will any of us exist after we die?

This is the biggest question of all, and it puts life in sharp perspective: life matters because it ends. The same is true of stories. And we are desperate—in writing and reading as in life—to know what the resolution will be. Doris Day can sing “Que Sera, Sera” until the cows come home, but most people aren’t content to accept that whatever will be, will be.

“We’re so close to something here,” John tells Rhoda at one point. And that is what a good story does: it brings you close to an understanding. A great story like this one recognizes the insult of spelling out what that “something” should mean. The reader constructs meaning, just as the writers and filmmakers constructed a story.

I think back to the confessional, the anxious wait outside the booth while another child murmured his transgressions to the priest. My own mind drifting, conjuring, scheming. Forgive me Father, for I have sinned. I made up my last two confessions and am working out this one’s plot and details as we speak. His reliable prescription, two Our Fathers and three Hail Marys, likely would have been the same either way.

When forced, or even when provided the opportunity, such efforts at being forgiven seem hollow. We must come to the realization and seek out forgiveness on our own for it to mean anything. Even as we absolve our public figures, we can’t help but notice the PR executives in the wings, poised in pressed suits, mouthing the speech. We know when something feels real instead of manufactured.

That’s the trick of writing a good story: manufacturing something that seems real. Writing is its own kind of confession, even if it’s not strictly confessional. And putting one’s creation out there is like making a very public confession: this is who I am, this is the way my mind works. A risky proposition.

But that is a crucial reason writers write and readers read and audiences watch films. With the possibility of risk comes the possibility of deeper understanding, deeper connection, a deeper self. For Rhoda, the risk that drives her is enormous and propels the film: forgiving herself for what she owns is an “unforgivable mistake.” If others are worthy of our forgiveness, aren’t we, too, worthy of our own? The possibility may seem as distant as a parallel planet. But there are many ways to write your ticket there.