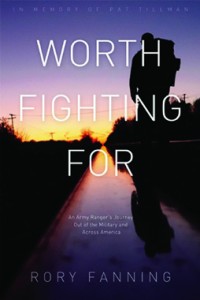

Worth Fighting For: An Army Ranger’s Journey Out of the Military and Across America

I wasn’t sure I’d like a book called Worth Fighting For by a former soldier who walked across the United States to raise money for the Pat Tillman Foundation. The website of that foundation celebrates military “service” and the “higher calling” for which Tillman left professional football, namely participation in the U.S. war on the people of Afghanistan and Iraq. Rather than funding efforts to put an end to war, as Tillman actually might have wished by the end of his life, the foundation hypes war participation, funds veterans, and to this day presents Tillman’s death thusly:

On the evening of April 22, 2004, Pat’s unit was ambushed as it traveled through the rugged canyon terrain of eastern Afghanistan. His heroic efforts to provide cover for fellow soldiers as they escaped from the canyon led to his untimely and tragic death via fratricide.

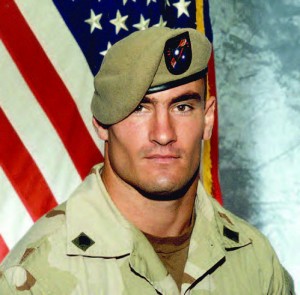

Those heroic efforts happened, if they happened, in the context of an illegal and immoral operation that had Tillman defending foreign invaders from Afghans defending their homes. And the last two words above (“via fratricide”) tell a different story from the rest of the paragraph, page, and, indeed, the entire website of the Pat Tillman Foundation. Tillman was shot by U.S. troops. And he may not have died a thoroughgoing supporter of what he was engaged in. On September 25, 2005, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that Tillman had become critical of the Iraq war and had scheduled a meeting with the prominent war critic Noam Chomsky to take place when he returned from Afghanistan, all information that Tillman’s mother and Chomsky later confirmed. Tillman couldn’t confirm it because he had died in Afghanistan in 2004 from three bullets to the forehead.

Rory Fanning’s book, Worth Fighting For: An Army Ranger’s Journey Out of the Military and Across America, relates, however, that Tillman looked forward to getting out of the military and sympathized with the actions of Fanning, a member of his battalion who became a conscientious objector and refused to fight. According to Fanning, Tillman “knew his very public circumstances forced him to stick it out.”

What made Pat Tillman a particular hero to many in the United States was that he had given up huge amounts of money to go to war. That he had passed up the opportunity to horde wealth in order to engage in something even more sinister doesn’t register with supporters of war. Incidentally, had the U.S. Army not killed him, and if he wasn’t then driven to kill himself (the leading cause of U.S. military deaths now being suicide), Tillman surely would have lengthened his life by leaving the National Football League, which abandons its players to an average lifespan in their mid-fifties, according to a University of North Carolina study, and in some cases, dementia in their forties—an issue that arises in Fanning’s book as he meets with former NFL greats to raise money for the Pat Tillman Foundation.

Photo in the Public Domain from U.S. Army

Tillman was, by all accounts, kind, humble, intelligent, courageous, and well intentioned. He clearly inspired many, many people whom he met, and others he never met, to be better people. Certainly Fanning would include himself in that list, but when he decided to walk across the country raising funds in the name of Pat Tillman, finding support and shelter for himself along the way, Fanning was playing on the beliefs of a propagandized public—beliefs he had ceased to fully share. A sheriff, in a typical example, takes Fanning’s empty water bottles, drives twelve miles to refill them, and hands them back to Fanning with tears in his eyes, saying, “What Pat did for our country is one of the bravest, most admirable things I can remember anyone doing. Take this for your cause.” And he handed Fanning $100.

Was generating hatred and resentment in Afghanistan by killing helpless people a service to the United States? Were the environmental destruction, economic cost, and eroded civil liberties a benefit to us all? Perhaps the answer is “yes” for those people the Pat Tillman Foundation is still trying to milk for money. Such a foundation does supplement the insufficient funding the government provides to care for veterans, but it also generates public support for and identification with supposed military heroism. It’s a double victory for the makers of war in Washington, most of whom are far more misguided than Tillman ever was, and who are more remarkable for their cowardice than their bravery.

As I said earlier, I wasn’t sure I’d like Fanning’s book. But I was very pleasantly surprised and recommend the book enthusiastically. It recounts an adventure worth having that contained no fighting at all. It’s a tale told with the wisdom, erudition, kindness, humor, humility, and generosity I think Tillman would have been proud of.

As he very publicly walks across the country, doing interviews, speaking at events, and chronicling his progress on a website (now gone), Fanning finds people going out of their way to help him. This does not, of course, prove that anyone without a public cause or celebrity label, or anyone of any race or sex or appearance could safely and successfully find the same sort of selfless support from so many Americans. Nonetheless, it’s heartening and encouraging to read. And these accounts come interspersed with descriptions and historical background on the places Fanning walks through that suggest he has a future as a travel writer if he wants it. Intermingled as well is an account of how Fanning moved from being “a devout Christian to an atheist and from a conservative Republican to a socialist.” He later adds that he ceased opposing environmentalists and became one. As this world needs such transformations on a large scale, a smart account by someone who’s been through several has great value.

One aspect of Fanning’s own drama that sheds light on the notion that Tillman was “forced” to “support the troops” even while being one (that is, support a war he may have disagreed with) is the description of how hard it was for Fanning to turn against the military (a process that may perhaps remain incomplete for him even now). Fanning had joined after 9-11 for reasons similar to Tillman’s, believing it was his duty. He then found he “did not have it in him” to kill. He saw the injustice and absurdity of capturing people falsely ratted out by rivals to an ignorant foreign occupier eager to punish (and torture) anyone it could. He came to see himself as an imperialist pawn rather than a rescuer on a mission for humanity. When he refused to go along to get along, he was ostracized and abused by everyone around him except Pat Tillman and his brother, Kevin. Despite his refusal to fight, Fanning was sent back to Afghanistan and made to do chores, labeled “bitch” by his commander, and forced to sleep outside alone in the snow. And Fanning supported his own abuse, attempting to make himself ill, afraid of the shame of his own behavior rather than wishing to expose the shame of the evil behavior of those around him.

Fanning recounts a conversation with a military chaplain during which he made the case that the whole war was unjust. The chaplain responded that God wanted him to do it anyway. The loser in that contest was apparently Fanning’s use for the concept of “God.”

But Fanning’s struggle continued within himself even after getting home and getting out. “After I left the military,” he writes, “the hardest thing I had to do was look someone in the eyes. I was afraid I would be exposed for breaking my oath.” Not for having been part of an operation of mass murder, but for having abandoned it. That’s how Fanning felt even after getting out, so one can imagine how Tillman felt while still in Afghanistan and while being treated as a god himself for being there. Fanning sees the contradiction. “I knew U.S. imperialism was destroying the planet,” he writes, “but I still felt guilty for leaving.”

In the course of Fanning’s walk he avoids mentioning what he (and perhaps Tillman) actually thought, until—three-quarters of the way along—a boy asks him which branch of the military to join. “I don’t think you should join any of them,” he answers. Then he gives the $100 from the sheriff to a homeless man under an overpass.