Digging in the Ideological Garden

Photo by Susan Gerbic (Creative Commons)

Photo by Susan Gerbic (Creative Commons) Eugenie Scott is an anthropologist and the former executive director of the National Center for Science Education, which she led from 1987-2013. She has a PhD in biological anthropology from the University of Missouri and has taught at the University of Kentucky, the University of Colorado, and at California State University, Hayward, focusing her research on medical anthropology and skeletal biology. Considered an expert on creationism and intelligent design, she’s also known as a strong advocate for church-state separation. Scott has received numerous honorary degrees and awards from educational, scientific, and secular organizations. She is a member of the California Academy of Sciences, a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and she served a term as president of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists. In 1998 the American Humanist Association awarded Scott the Isaac Asimov Science Award. The following is adapted from her June 7, 2014, speech in acceptance of the AHA’s Lifetime Achievement Award at their annual conference in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

I WAS ASKED to say a few words upon receipt of this really quite wonderful recognition, which I appreciate more than I can possibly describe to you. Because a lot of what I’ve done over the years at the National Center for Science Education deals with science and religion, I thought I would use this opportunity to share my perspective on the relationship between these two subjects. This is a very important topic to humanists, to other nonbelievers, and to believers as well, and it’s also important to the role of science in our nation.

There are people who want to replace religion with science—who believe that science makes religion obsolete or that science can substitute for religion. There are even people who, like fundamentalist Christians, claim that one must make a choice: you can have science or religion, not both. I think this is a mistaken view of what science is and what science does, and it’s also an incomplete understanding of what religion is and what religion does.

I think the creationism/evolution controversy is partly to blame for this confusion, because many of us started thinking about religion, quite honestly, in the context of the creationists, who are using religion to explain the origin of the universe, of Earth, and of living things, including people. We get the idea that religion is primarily about explaining the natural world, whereas religion in general and Christianity in particular are concerned in only a very small way with the natural world. What Christianity and virtually all other religions are concerned with is meaning, purpose, and how people relate to one another, and to God. But the creationists place a huge emphasis on Genesis, and unlike most Christians, are obsessed with using God to explain the natural world. I assure you, most Christians do not sit up nights worrying about the Cambrian explosion.

Unfortunately for creationists, when it comes to explaining and understanding the natural world, science wins. The “revealed truth” of the Bible, or the Koran, or the Gitas, or any other sacred source simply cannot explain the natural world with accuracy. When creationists make factual claims about the age of the Earth, or the dinosaurs and humans living together, or the origin of the Grand Canyon after Noah’s Flood, they fail. Science has better explanations. But that doesn’t make science a worldview. It doesn’t make science a religion substitute. Science is a way of knowing—an epistemology, not a philosophical worldview. Let me explain why I look at it that way.

I like to think of science as a limited way of knowing, an attempt to explain the natural world using natural processes. We don’t attempt to answer all questions human beings seek to answer. For example, I can’t give you a scientific explanation for why Mozart is better than Madonna, or Madonna is better than Mozart. I can’t tell you scientifically whether it’s right for a Native American girl to refuse cancer treatments because it conflicts with her conception of her body and its relationship to nature. There are many things that are important to people that science does not directly address. My position is that often science can inform our philosophical views but that doesn’t make science per se a philosophical system or a way of life. I think part of the confusion arises because there is a philosophical system that parallels science. Let me distinguish what I mean here.

We use the term “materialism” or “naturalism” in two ways. In science, we talk about methodological materialism or methodological naturalism, and this is a rule that we scientists use in restricting ourselves to natural causes when we explain the natural world. We don’t use God. We don’t use gods, ancestor spirits, or the supernatural in our explanations. And when creationists and intelligent design proponents do, we rightly criticize them for it. We criticize them for not doing science.

Now, the reason we don’t use supernatural forces in explaining the natural world is not because scientists are inherently antireligious; about one-third of scientists at elite institutions believe in God or a higher power, and higher percentages exist at less elite institutions. No, the reason we restrict ourselves to natural (material) causes is because those are the only ones we can test. And if science is about anything, it’s about testing our explanations.

Now, how do we test stuff? The bottom line is that you have to hold constant certain variables, certain elements of the problem you’re looking at, so that you can see whether your explanation is really the one that’s valid. If there is an omnipotent power or powers in the world, which you and I as humanists don’t believe, there’s no way by definition you can hold constant the actions of those entities. You cannot put God in a test tube—or keep him out of one.

So, as scientists, we set God aside. And you know something? It works really well. We have explained a phenomenal amount about how the natural world works by restricting ourselves to natural causes, which is why when the intelligent design proponents say, “We have to abandon methodological naturalism, we have to bring in the supernatural when we’re talking about origin science,” we say no, our way works just fine. It ain’t broke, so we’re not fixing it.

Now, there also is something called philosophical or ontological materialism. This is an assumption, a first principle, if you will, that there is only matter and energy in the universe. My physicist friends would say matter, energy, and their interactions, but let’s not get too fussy. If you’re a philosopher of science, ontological materialism says that the matter-and-energy universe that we experience is really all there is, and this perspective is, in many respects, the foundation of humanism. I personally am very comfortable with philosophical materialism. But please do understand that methodological materialism is not the same as philosophical materialism. The philosophical assumption that we make as humanists is not the same as the methodological assumption made by scientists—who can be believers or nonbelievers.

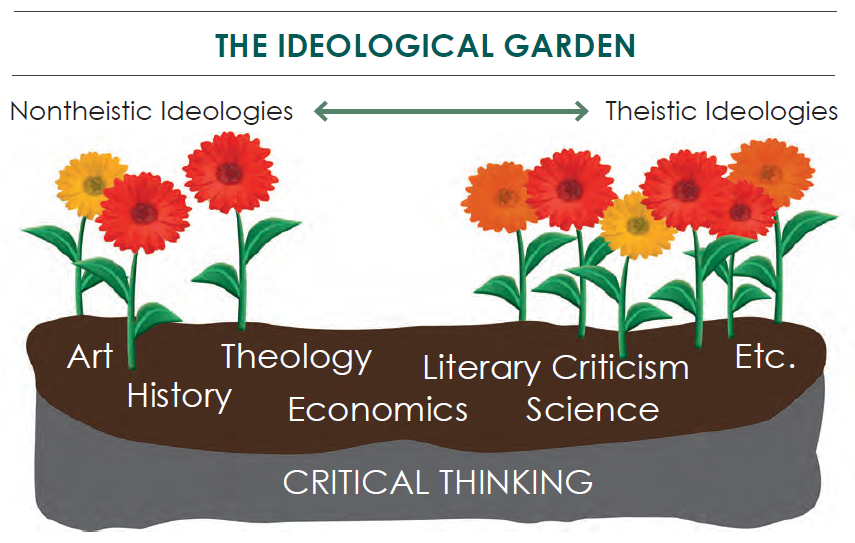

Visualize a garden. The flowers are in competition with each other for things like water and sunlight and nutrients. It would be silly to think of the flowers as being in competition with the soil, which nourishes all the flowers. Now, if this is an ideological garden, we can look at the flowers as representing ideologies, religions, philosophies, or worldviews. Some of these views are theistic—there are many, and they are in competition with one another for hearts and minds. Some views are nontheistic, and there are many of these as well—not just humanism and other secular traditions dealing with ethics, morals, meaning, and purpose, but other “-isms” like capitalism, environmentalism, socialism, feminism, and Marxism. Now, we all have overlapping ideologies. I’m not anti-ideology; I’ve got a whole suite of them and so do you. You can be a humanist capitalist. You can be a socialist feminist. Our ideologies are what shape our view of life and shape the way we behave. So, they are very important.

Now, the theistic ideologies and the nontheistic ideologies are in competition with each other. Both theistic and nontheistic philosophies claim to be inspired by science, which, again, is methodologically naturalistic, not philosophically naturalistic. Think of science as equivalent to the soil of a garden, nourishing the ideologies but not itself being an ideology, any more than soil is flowers. Science per se is not a philosophy of life. That’s philosophical materialism. The philosophies are above the soil of science, so to speak, and the ideological flowers are in competition with one another, not with the soil. Science is used to support the views above the soil, but it cannot be claimed to compel any particular view. Like the soil, science is an equal opportunity substratum for ideologies.

It’s perfectly fine, however, to contend that one -ism is better supported by science than another, and we do that all the time. For example, humanism is a better fit with science than is biblical literalism. Our plant has better DNA to take advantage of the soil of science. But the debate should take place between science and among the -isms; none of the -isms have a right to seize science for themselves.

There’s more. Just as soil is underlain by bedrock that nourishes or replenishes it in various ways, so critical thinking underlies science. Critical thinking, briefly, is the process of collecting and evaluating information, logically relating elements to come up with some sort of a conclusion about the topic of interest. But critical thinking also underlies other intellectual pursuits in addition to science: history, theology, economics, art, philosophy, and so on. Done properly, all of these intellectual disciplines utilize the process of critical thinking and they in turn influence our ideologies, theistic or otherwise. Yes, there is crummy history. There is crummy theology and there is crummy science. Critical thinking isn’t always employed as well as we might like it to be, but it does distinguish us from lower organisms.

Thus I hope that we can encourage everyone, regardless of ideology, to be a critical thinker and to appreciate science. Certainly there can be a vigorous ideological discussion among the flowers in the ideological garden, between and among theists and between theists and nontheists, with science left out of the culture wars. I reiterate, it’s perfectly reasonable for the ideologies to argue over whose views are better supported by science, but that’s quite different from claiming that the ideologies are in competition with the soil or that any particular ideology owns science or that science or any other human intellectual endeavor owns critical thinking—much less that one needs to choose between science and one’s -isms. Everyone needs science. Everyone needs critical thinking, and, ideally, we will evaluate our -isms accordingly. Because ultimately, humanism and religion, especially the Christian religion predominant in the United States, are much more concerned with, “What’s it all about?” than, “How did we get on land?”

I was very privileged to have worked for the National Center for Science Education (NCSE) for so many years, and I strongly urge you to look at all the information and resources on our website. For instance, we have a climate science page now because teachers get hammered for teaching that just like they get hammered for teaching evolution. And I do want to thank all my colleagues there, including the new executive director, Ann Reid. She is doing a fabulous job, and I know you’ll give her the same sort of warmth and support and enthusiasm for NCSE that you’ve given me all these years. Thank you.

Q&A

Q: Is there a particular nugget of science that you love to explain to kids?

Eugenie Scott: As a humanist, I’ve always thought that we would go a long way toward helping to understand a number of the social problems that we have in our society if we understood the concept of phenotype better. Phenotype is a fairly simple biological concept that says that virtually everything about us—our stature, our height, eye and hair color, our level of intelligence—is the result of our genes plus the environment plus the interaction of those two. There is nothing that is determined about us.

Judging by anthropological rule of thumb, given my husband’s height and my height, my daughter should’ve been 5’10” because mid-parental height is the best prediction. She’s a little bit shorter than that because just when she was going through her growth spurt, she happened to get a slight, long-term fever that stunted her growth, so to speak. Okay, that’s environment interacting with genes. Everything about us is genes plus environment. So, if somebody tries to tell you that groups of human beings on different continents are smarter or less smart, better at sports or worse, tell them about the concept of phenotype. If people tell you that women are good at math or not good at math, tell them about the concept of phenotype. I think it’s a useful thing for kids to know about.

Dr. Scott talks to 2014 AHA Annual Conference attendees.

Q: How long do you think it will take for the NCSE to put a stake in the heart of climate change denial?

Eugenie Scott: You know, I wish I could say we put a stake in the heart of creationism. We did stop intelligent design in its tracks but its proponents haven’t gone away, they just morphed. And the Young Earth creationists are alive and well. The climate change issue is so critically important for civilization, quite honestly. I mean, the species is going to go on. We’re like rats and pigeons, we will continue as a species. But if the kinds of sea level rise, ocean acidification, and other aspects of climate change that are predicted by some of the best modelers do take place over the next fifty to seventy-five years, we’ll see mass migration of people, wars over things like water, and what probably is best described as the breakdown of civilization. I hate to sound like a crazy alarmist but the circumstances are extremely serious.

It was recently reported that the West Antarctic ice sheet is reaching the point of no return in terms of the amount of melting that’s taken place underneath it. Pretty soon the whole ice sheet is going to go, which will seriously raise the level of the ocean. Forget about Florida. Forget about large portions of South Asia. There are already a whole lot of people in Bangladesh. They’re going to be moving into the interior of the country.

But even if we stopped using all kinds of carbon tomorrow, the West Antarctic ice sheet is still going to melt. And we don’t know how many more processes like that are unstoppable or irreversible. I really hope that people start paying more attention to ocean acidification, which doesn’t get as much attention as global warming. But when you consider how much human beings depend on the ocean, especially for protein supplies, you realize that ocean acidification is an extraordinarily serious problem. I’m pessimistic because I hang out with climate scientists.

Q: What’s your degree of certainty that the warming is primarily due to human causes?

Eugenie Scott: According to climate scientists who advise the NCSE, the planet is warming, no question. Even the deniers are having a tough time arguing that it’s not warming. As for how much of it is anthropogenic, climate scientists attribute ninety-plus percent to human activity.

Q: What do you think of the idea of teaching creationism in mythology classes?

Eugenie Scott: I like it. I’m an anthropologist, and I think that we not only have a very low level of scientific literacy in the United States, we have a very low level of theological literacy as well. We might know something about Christianity but here’s a newsflash: it’s not the only religion.

I’ve tried hard to come up with a definition of religion that would fit all of the religions that we know about. Every human society has some sort of conception that could be described as religion, but they don’t all deal with the supernatural, they don’t all deal with ethics and morals, and so on. So what’s the common element that you can say occurs across all human religions? Basically, what I’ve come up with is the concept that religions link human beings to a reality that’s not material, that’s beyond the matter-and-energy universe in which we live. It can be God in heaven; it can be the ancestor spirits.

I think we really need to teach more about religion. But it has to be done descriptively and in a neutral fashion. You can’t say, “here are all these religions but Buddha was right” or “Jesus was right.” You’ve got to respect the First Amendment and respect the right of children not to be proselytized in school. If we really understood the variety of religious views out there and the variety of ideas that are subsumed in religion, I think we’d be spending a lot less time trying to deal with people who are trying to explain the natural world with religion, because actually that’s such a tiny, tiny slice of what religion is all about.

Humanism, not science, is in opposition to theism. And I am incredibly honored that the American Humanist Association would give me a lifetime achievement award. Thank you.