A Bridge Supreme: Connecting Humanism to a Liberal, Loving Christianity

Photo by Dick Snyder

Photo by Dick Snyder John Shelby Spong was the Episcopal Bishop of Newark for over two decades before his retirement in 2000. As a visiting lecturer at Harvard and at universities and churches throughout North America and the English-speaking world, he is one of the leading voices for liberal Christianity, initiating landmark discussions on controversial topics within the church as an outspoken advocate for change.

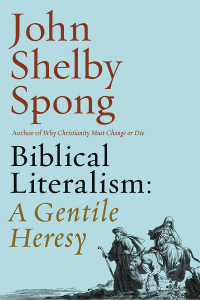

Spong is the author of some twenty-five books, including Re-Claiming the Bible for a Non-Religious World; Rescuing the Bible from Fundamentalism; Why Christianity Must Change or Die; and his autobiography, Here I Stand. His newest book, Biblical Literalism: A Gentile Heresy, was published in March.

On May 27, 2016, Bishop Spong was honored with the American Humanist Association’s Religious Liberty Award at the AHA’s 75th Annual Conference. The following has been adapted from his remarks in acceptance of the award.

I WOULD LIKE to thank all of you for your invitation both to address this gathering and for this honor. I am very pleased to be here.

As I walked in, I saw an interesting slogan. It said: “Good without a god.” I would like to tell you that I was a bishop for forty years and I know it is quite easy to be evil with God. And I suspect the other alternatives are also that it is easy to be evil without God and good with God. So slogans do not always tell the whole truth. In the course of my life, I have had sixteen death threats but never by an atheist. I have never had a Buddhist threaten my life. The only people who have threatened my life have been true-believing, Bible-quoting Christians. They seem to have missed that part in the Bible that says thou shalt not kill, which I think is rather interesting.

I was born in the Bible Belt of the South. I grew up about one quarter of a mile from the house in which Billy Graham grew up. When I was a teenager, I delivered the Charlotte Observer to the Graham household for about three years. I am happy to tell you they always paid their bill and on time. But it was the same religious milieu. Billy Graham and my mother went to the same church. So it should not be surprising for me to discover that most of my prejudices I learned inside Christian churches.

The church in which I was raised in Charlotte, North Carolina, taught me that segregation was the will of God. They taught me that men were by their nature superior to women. They taught me that it was okay to hate other religions and most especially the Jews. And they taught me that homosexuals were either mentally sick or morally depraved and they should be either cured or persecuted. The fascinating thing is that as they taught me these things they quoted the Bible to justify each deep, distorted prejudice. The Bible has sixty-six books, seventy-nine if you count the Apocrypha. And you can find something in there that you can quote for almost any situation imaginable.

Some years ago, I was the first religious person to be invited to deliver a lecture at the Hemlock Society (which now goes by the name Compassion in Dying). It’s a wonderful organization, on whose board I served for a while. The reason religious people have never come to this understanding is that they seem to think that the issue of life and death should be left in God’s hands and not put in any human hands. As I prepared for that lecture, I went through the Bible and I pulled out every sin, weakness, and flaw that, if committed by a human being, called for the death penalty. Folks, I want to tell you there would not be one of us still alive if we took the Bible literally.

The Bible says in Deuteronomy that if you are willfully disrespectful of your parents and talk back to them, you shall be given to the elders of the city and stoned until dead at the gates of the city. Raise your hands, please, those of you who would still be alive. The Bible also says that if you have sex outside your marriage, you should be put to death, but I will not ask you to raise your hands on that score. There were others, like, worshipping a false god. Well, who is going to define the true God? Is it going to be the pope? Is it going to be Jerry Falwell? Is it going to be the Ayatollah? Is it going to be Ian Paisley? No matter who defines God, somebody is going to be vulnerable to execution.

My favorite was the death penalty for having sex with your mother-in-law. How many of you knew that was in the Bible? How many of you ever heard anybody speak on that subject? How many of you have even imagined it? And the reason you laugh is that you just tried. You have got to be very careful when you begin to quote the Bible to justify all of your prejudices.

My favorite was the death penalty for having sex with your mother-in-law. How many of you knew that was in the Bible? How many of you ever heard anybody speak on that subject? How many of you have even imagined it? And the reason you laugh is that you just tried. You have got to be very careful when you begin to quote the Bible to justify all of your prejudices.

As I grew up in this church, I had to come to grips with all sorts of things that did not fit for me. One of the ways many people do that is to finally abandon the whole religious enterprise. For reasons I am not fully aware of, that was never the path I took. Instead I went more deeply into the religious enterprise and found a new level of meaning and a new level of understanding.

Let me go back to some of those prejudices for just a moment. First: “a man is by his nature superior to a woman.” That is a point of view we have held in the Western world for a very long time. That is why American women could not attend college or own property in their own names until the nineteenth century. And in the life of the church, women could not be ordained because somehow the defective body of a woman meant that she did not bear the image of God.

Prejudices are rather irrational. Let me unload that one for just a moment: consider a man and a woman standing before you and begin to strip away from the man’s body everything he has in common with the woman’s body. It is about 99.9 percent. Strip it all away looking for where the image of God is. And you get down to that single identifiable male organ and you are forced to say, that is where the image of God lives. Is that not irrational? And yet for hundreds of years in the Christian church, this has been the argument for an all-male priesthood. They say it is a sacred tradition. But I think of it as nothing except an ongoing prejudice, one that embarrasses me and that I think should embarrass the Christian church.

Look at the battle we have had over gay rights in this country. By and large the Christian church has been on the wrong side of that battle, and again, the irrationality of the definition was amazing. The primary reason that people thought it was okay to be prejudiced against gay and lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people is that they assumed that these people had chosen this lifestyle. They even used the word “lifestyle.” They assumed that they chose to be this deviant kind of person.

Well, I do not know of a scientist or a doctor in the developed world today who thinks that people choose their sexual orientation. How many of those of you who are heterosexual remember the day you chose to be heterosexual? I did not choose. I just woke up sometime between ages twelve and thirteen and suddenly girls did not seem obnoxious to me any longer. I did not make a decision about that. But I began to do really strange things like take baths and use deodorant and comb my hair and dress a little more neatly.

But if you and I do not choose our sexual orientation, I wonder why we have assumed that gay and lesbian people do—and that because they do, they are blameworthy. It is a rather amazing bit of ignorance. And yet look at how long it has been perpetuated in church, in society, and still in great pockets of this country.

Let me go to the prejudice that I think is most uniquely Christian. When I was going to Sunday school in North Carolina and being taught the Bible, I never once was introduced to a good Jew. There appear to be no good Jews in the Bible. Every Jew I met was dark and sinister and evil. They had funny names like Caiaphas, Ananias, Sadducees and Pharisees, and of course Judas Iscariot. You know, in all the time I was going to Sunday school, nobody ever told me that Jesus was a Jew. Somehow that escaped their notice. I looked at a picture of him and he did not look Jewish to me at all. He had blond hair and blue eyes and fair skin. I assumed he was a Swede. Judaism is the womb in which the Christian story was born. Judaism is our mother. And we have spent hundreds and thousands of years spitting on our mother.

Fortunately, that is changing. For example, a professor of the New Testament at Vanderbilt Theological School is a Jewish woman, Amy-Jill Levine. She is a magnificent scholar. And here we have a Jewish scholar teaching future clergy the New Testament. That is a sign of things to come. Géza Vermes is another great figure. He started his life as an Orthodox Jew, converted to Roman Catholicism, and later reconverted to Judaism. So he has looked at religion from all sides, and he has helped people understand the other point of view. And that kind of rapprochement is beginning to develop.

There are some things about the Bible I think humanists ought to know because I think they are important to the things you value. In the story of the judgment that only Matthew tells, the judge comes at the end of time and separates the nations of the world between the sheep and the goats. And then the judge tells them the basis upon which that judgment is being made. It has nothing to do with believing the creed. It has nothing to do with whether you have been baptized or confirmed. It has nothing to do with how often you have gone to church. The standard of judgment in the Gospel of Matthew is whether you have been able to see the holiness of God in the life of your fellow human being, even those who are “the least of these.” Even those upon whom you have been taught to look down. That is a humanistic standard, and, I think, a profoundly religious standard at the same time.

Only one time in the New Testament does Jesus articulate his purpose or have his purpose articulated for him. That is in John’s Gospel, written around seventy years after Jesus died. Once again, it seems to me that this is a place where humanist and religious people can find unity. Because Jesus says, “I have come that they might have life and have it abundantly.” Nothing about being religious. Nothing about saying creeds. Everything about the quality of your life.

Photo by Carissa Snedeker

It seems to me that humanism is a philosophy of life that encourages us to be more humane. To be anti-humanist is to be inhumane. I, as a Christian, see my humanist brothers and sisters as my allies in the attempt to build a humane world where the humanity of every child of God will be totally respected.

When I see God or talk about God, I do not talk about the theistic supernatural old man in the sky. I talk about the experience. When I think of God, I think of life calling me to live, to live fully. I think of love freeing me to love, to love beyond my boundaries and beyond my barriers; free to give my love away wastefully, never stopping to count the cost. Finally, when I think about God, I think about the ground of all being that gives me the courage to be all that I can be.

The task of the Christian church is not to convert the world to some religious ideology. The task of the Christian church is to free every person in this world to live more fully, to love more wastefully, and to have the courage to be all that they can be in the infinite variety of our humanity. I submit, my brothers and sisters, that that is not far removed from the ideals and the goals of the American Humanist Association. So I salute you as my allies in the attempt to build a more human and a more humane world. Thank you very much.

Excerpts from the Q&A

John Shelby Spong: I do have a rule. The first question has to come from a woman. And every other question after that has to come from a woman. I refuse to participate in the male attempt to silence the female voice in this country.

Q: Okay, you got your first woman. As a humanist, I’ve always stayed away from religion until I got exposed to Pope Francis. I really admire his stand and want to know how you relate to Pope Francis.

A: Without being negative, let me say I think anybody they elected would have been an improvement. I think they hit the bottom with Benedict XVI. He used to refer to homosexual people as deviant. I was doing a lecture at the law school at Marquette University and I quoted him. I was challenged by one of the professors who happened to be a Jesuit priest. He said, “That is not what Pope Benedict XVI means by deviant. He means that you have placed yourself in a position where you cannot reproduce.” And I said, “Then all of your clergy are deviant, are they not?” That discussion did not go very far.

But I think Francis is a great and gracious human being. And moving that institution forward is not easy. I mean, in the nineteenth century they declared themselves infallible. And it is awfully hard to change when you have already decided that you are infallible. That does not lend itself to progress. But thank you for your question.

Q: My question may sound flippant, but I would love to know: How on this earth did you ever get promoted?

A: Let me give you a commercial for my church. The Episcopal Church is part of the Church of England. The Reformation was not ideological—everybody in England had to be a member of the Church of England, so it had to be broad enough to incorporate the whole population. So you can be an Anglican and be as Catholic as the pope or as evangelical as Jerry Falwell and you’ll still be an Anglican. So there is a broadness about a church that was not founded on the basis of a creed but on the basis of a nation.

This church has, over the centuries, encouraged not everybody, but encouraged some people to press the boundaries of its life theologically. They always meet great resistance. But about a generation after they have died, their point of view becomes the new orthodoxy, and their opponents are long forgotten. And so I lived happily within it.

I was never forced out. The fierce opposition came when I ordained the first openly partnered gay man to the priesthood in America and indeed in the Anglican Communion. That was in 1989. It was an incredible experience for me. It was also an incredible experience for those close to me because the hostility was overwhelming. I received about 5,000 letters a week for a period of time. And about 4,999 of them were hostile.

My wife and I would go to lectures, and we would be spat upon by Christian protesters as we walked into the venue. Fred Phelps from the Westboro Baptist Church in Topeka, Kansas, picketed me every time I came within 500 miles of Topeka. I guess after a while my church decided that they had to do something, so they introduced a resolution to disassociate themselves with the Bishop of Newark and his diocese for ordaining a gay man.

When they met to vote on this, they went through three hours of debate. And when they finally had the vote, the final count was seventy-eight in favor of disassociating themselves with me and seventy-four opposed, with two abstentions. And I was one of the two abstentions because I did not know how to vote on whether I wanted to associate with myself or not.

I had an agreement with the presiding officer, that I would not participate in the debate (because there was no doubt about the fact that I had done this thing) but would have the privilege of addressing the House of Bishops after the vote no matter how it went.

And so I stood up immediately and the presiding bishop recognized me. I am enough of a politician to know you take a power position when you can. So I walked up to the presiding bishop’s desk, pushed him aside, took over the microphone in the center of the room, and delivered a forty-five-minute purple-passionate oratory on my own life and how I had gone from the homophobia of my childhood to the position where I was willing to risk my life and my career for the sake of justice for gay and lesbian people.

When I finished, I received what I call a semi-standing ovation. That is, those that stood ovated and those who did not stand did not ovate. I returned to my desk and some twelve bishops came over and said, “If I could have heard what you said before the vote, I would have voted in favor of you.” I knew at that moment that we had a majority in the House of Bishops on that issue, and that majority never failed.

Today, my church has two out-of-the-closet partnered bishops serving openly, one in California and one in New Hampshire. The one in New Hampshire has just retired. But when I retired as the bishop, I had thirty-five out-of-the-closet gay and lesbian clergy serving in the Diocese of Newark. Thirty-one of them lived openly with their partners. And I must tell you, I have never had a complaint about any kind of sexual misbehavior from any of my gay and lesbian clergy. I cannot say that about my heterosexual clergy.

So I have a great affection for my church, which has allowed me to live within it and to push it into new positions. I do not really have to push it anymore because they have caught up. I am not even controversial. They now refer to me as our beloved old bishop. That is a status that comes just before you die. Thank you for your question, and thanks to you all. I loved being with you.