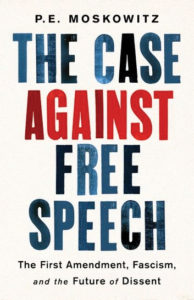

The Case Against Free Speech: The First Amendment, Fascism, and the Future of Dissent

P.E. MOSKOWITZ

BOLD TYPE BOOKS, 2019

272 PP.; $28.00

Words like “controversial” and “provocative” are overused. When you read or hear that so-and-so’s stand-up comedy is “controversial,” that’s usually the culture-war commentariat wishing that reaction into being rather than actually describing a pre-existing reaction. Which is why for every one person who finds it controversial, there are a thousand people who’ve been convinced that many people find it controversial and that such a reaction is something to be angry about. Of course, the politics of controversy is a means of distraction. If you’re thinking and talking about whether so-and-so’s stand-up is controversial, you aren’t thinking and talking about (say) healthcare or food regulation or employee-employer relations. Likewise, when you read or hear that such-and-such speaker is “provocative,” that often means they say things like feminists are ugly, blacks are naturally stupid, and the poor deserve their misery. These things have been said for decades and centuries. I suppose they do provoke reactions, especially among young people who haven’t heard such things yet, and so in a narrow sense are provocative. But the word is mostly a media euphemism; a way of seeming objective and even-handed. In other words, a way of obscuring.

P.E. Moskowitz’s new book, The Case Against Free Speech, has what many would call a provocative (even controversial) title, although, like the controversial stand-ups and provocative speakers, upon investigation its actual substance is rather tame. On page one Moskowitz clarifies that his book isn’t anti-free speech but only “anti-the-concept-of-free-speech” (meaning he doesn’t think free speech exists or ever has) and that he doesn’t favor censorship laws that prohibit fascist and racist speech.

Moskowitz gives two reasons for why he thinks free speech “as a concept… [is] meaningless.” First, because with inequalities of power and wealth, the notion that all of us—rich, poor, and in-between—share and enjoy a common individual liberty like free speech is political mumbo-jumbo. The rich spend hundreds of millions of dollars every year so their political desires are heard; the rest of us can be fired for speaking out of line at work. Those without power are harassed and surveilled by the police, and this harassment and surveillance has its effects on people’s willingness to speak freely.

Moskowitz points to his talks with Black Lives Matter activists who were harassed and surveilled by the police for months before a judge ordered the police to stop (or, more precisely, to stop being so obvious), as well as Standing Rock protesters who, while encamped, were surrounded by police, spied on overhead by drones, tracked by private security companies, and had their camp infiltrated by informants. The Standing Rock protest was most notable not for its size or duration but for the scale of the state’s response. Protesting the construction of a single pipeline, the state responded with extreme force and total surveillance.

In truth, more harm is done in a single executives’ meeting (and a hell of a lot more at a single meeting of some “dark money” political foundation) than was done by those protesters. And yet those meetings don’t have drones buzzing overhead. No FBI infiltrators. The powerful speak freely and the rest of us suffer in silence (or will be made to). While the company CEO golfs with the attorney general and talks about easing up on enforcement of labor laws, the entire workforce is fired off for talking amongst themselves about unionizing or just joking about how much of a hellhole working there is.

A concrete instance of this occurred recently when Koch Foods settled a class-action lawsuit brought against the company by some of their food-processing workers in Mississippi; a few months later, ICE raided the company’s food-processing plants and arrested almost 240 workers. The obvious lesson for migrant workers being: speak up and you run the risk of getting deported.

The second reason Moskowitz gives for thinking free speech is conceptually meaningless is that we already censor speech in favor of other values, such as privacy, property rights, and even economic efficiency. A bank lying to you about the interest rate on a loan, a company using a celebrity look-a-like to sell products, a tapped phone conversation, an emergency medical responder filming the person they’ve saved, starting a company called Facebook—these are all forms of speech (or at least attorneys have tried to argue they are), but the Supreme Court has ruled that none of them are protected by the First Amendment.

The criminalization and/or prevention of all these things is effectively censorship; the state is telling you that you aren’t allowed to speak in certain places or say certain things. (In cases of “professional speech,” such as equal protection laws for home ownership, the state literally mandates that you say certain things, otherwise you can’t conduct business in that industry). But these laws aren’t seen as censorious—or as attacks on our “culture of free speech”—because they’re generally recognized as protecting other fundamental values. As Moskowitz mockingly puts it, everyone would look sideways at the person who breaks into his or her neighbors’ houses to berate them, then defends their actions by saying, “No interest of home ownership outweighs the rights of someone to come into your house and yell at you.” The value of dominion over your own home is weighted above your neighbor’s right to be heard. The issue clearly isn’t between free speech and censorship, then, but between free speech and other values. Which raises the question: How should we decide which value wins over the others?

Moskowitz uses the case of Nazi Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie (1977) to illustrate how the false pretense of free speech as an absolute value is used by bigots and fascists. In 1976, the Nazi Socialist Party of America wanted a permit to march in the majority Jewish neighborhood of Skokie, Illinois. The village tried blocking the rally by passing ordinances forbidding events where participants planned to wear military-style outfits and by requiring all rallies to provide $350,000 in insurance money beforehand. Famously, the ACLU defended the fascists in court—in response the ACLU’s Illinois chapter lost a quarter of its membership—and eventually won them the right to march through Skokie. The rally never happened. Frank Collin, the leader of the Nazi Socialist Party, said he was just fighting for “free speech for white Americans” (yes, fascists were already using this shtick in the 1970s), and with the Supreme Court victory there was no need to actually go through with the rally. Of course, many suspected the rally never happening had less to do with that and more to do with the Jewish Defense League telling Collin that if he came into Skokie they’d make sure he left in a body bag.

Like fascist rallies today, when the Nazi Socialist Party did march around Chicago they got a police escort. Why exactly? As a Chicago columnist wrote at the time:

If I wanted to stand outside Wally’s Polish Pump Room this Saturday and shout that everybody who eats Polish sausage is a pig, I suppose that would be my constitutional right. At least the ACLU would probably think so. However, I don’t think I should expect the city to give me a police escort when I go there.

I suspect that if I and few of my friends walked around rich neighborhoods with a fake guillotine chanting “The capitalists will not divide us,” the only police escort we’d be getting is one to the station (handled with as much care as the Jewish Defense League would’ve given Collin and his fascist stooges).

Radical protests get police violence; fascist protests get police escorts. Some of the reasons for this are probably sinister, but one that isn’t has to do with the different tactics of the two protest groups. Radical protests are usually in sympathetic places; they’re done in order to rally mass support for something. Fascist protests, on the other hand, are usually in hostile places; they’re there to invoke a response so they can play the victim later. I agree with those who say anti-fascists should hold rallies of their own rather than counter-protest fascist ones. But I also can’t blame communities like Skokie and groups like the Jewish Defense League for pronouncing that if you come to provoke a reaction you will absolutely get one. The least the rest of us can do is not fall for the fascists playing the victim afterward or pretend that their rallies have anything to do with free speech.

The Case Against Free Speech isn›t very deep in analysis or original in thought. Anyone who’s read literary theorist Stanley Fish will already be familiar with most of the book’s “anti-the-concept-of-free-speech” premises. The Case Against Free Speech is, however, a much-needed, easy-to-read primer on a subject that seems to be given unlimited attention but zero thought. Establishment press outlets run hundreds of op-eds a year on “the crisis of free speech” just because their columnists are the laughing stock of Twitter. When right-wing media isn’t reporting on a migrant worker getting pulled over for drunk driving or a black man in Chicago caught stealing a refrigerator, they’re covering some college scandal like Alice Walker’s books being taught in a class outside the African-American Studies department. Koch-coordinated political foundations have spent hundreds of millions of dollars over the last thirty years making it seem as if free speech in academia is the defining political issue of our time, creating a network of organizations and websites like College Fix and Campus Reform that encourage college students to spy and snitch on one another for being too politically correct, then trickling these stories (and sometimes just directly paying for them to be published) into the media.

At one point, Moskowitz asks, “What’s the return on investment” for billionaires spending so much money on free speech and political correctness? His answer is that it’s their way of controlling universities. Similar to fascists using “free speech” as a smokescreen for their politics, billionaires use “political correctness” as a smokescreen for their interests. While there’s definitely some truth to this, the rich already effectively control universities through donations and by sitting on college boards. The board of higher education in most states is a who’s who of owners and executives. At George Mason, the Koch Brothers had a say in the hiring and firing of professors.

As I wrote at the beginning of this review, I think most of the debate on free speech—”political correctness,” “cancel culture,” “trigger warnings,” etc.—is just a distraction. A way of controlling how and what people think about when they think they’re thinking about politics. A sort of anti-politics that distracts people so nothing happens. That’s why the PC hysteria is identical to what it was thirty years ago. We argue amongst ourselves about college speakers and stand-up comedians while the rich do whatever they want on everything else. Moskowitz is right that in an unequal society, free speech is an impossible ideal. Which is just another reason to fight for a society more equal in wealth and power.