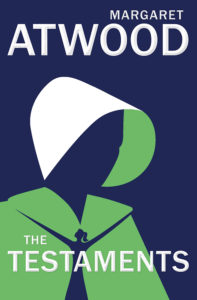

The Testaments

BY MARGARET ATWOOD

NAN A. TALESE, 2019

432 PP.; $28.95

[Mild spoiler alert: this review contains plot details of the book.]

During the torture session conducted by the Big Brother interrogator O’Brien in George Orwell’s 1984, the doomed Winston Smith, on being told how powerful and eternal the regime is, says through broken teeth: “Something will defeat you … evil cannot sustain itself.”

That is the theme of Margaret Atwood’s long-awaited sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale. The title is The Testaments, but it could just as easily have been called “How Theocracies Perish.”

Set fifteen years after the van door slammed shut on Handmaid’s protagonist Offred, the new novel shows a Gilead still standing. (The Republic of Gilead, for those unfamiliar with the story, is the theocratic state that has overthrown the US government). Women are still locked into Old Testament strictures; they aren’t allowed to read, write, hold a job, or drive a car. Those with notions of independence from pre-Gilead days are still herded into the regime’s “re-education camps,” presided over by the cattle-prod-wielding “Aunts”—infertile women tasked with destroying the psyches of these prisoners. And women are still blamed for inciting male rape.

Although the sustainable birth rate has increased a bit, there is still a need for Handmaids, fertile women who are essentially raped every month by their “Commander,” who is the head of the household and holds a position in the government.

This time around, though, something’s not quite right in Gilead. The clothes are more threadbare, the towels rougher, and there is a noticeable lack of consumer goods. Wars are still being fought against Baptists in Texas (now its own country) and against Mormons and Quakers in the Midwest, but the regime is not winning them. And Gilead is weakened to the point where resistance forces in Canada can now perform commando operations inside Gilead.

Worse, their valued “birthing machines,” the Handmaids, are fleeing to Canada in large numbers.

Margaret Atwood, 1987 Humanist of the Year

In The Handmaid’s Tale, published in 1985, the hypocrisy practiced by the government was subtle and confined to male sexuality. Male leaders violated the founding principles of the Old Testament regime by hoarding porn and creating a night club filled with scantily clad women for hedonistic sex.

Fifteen years later, the corruption has spread and is more homicidal.

Leaders kill founders and each other either in purge trials or suspicious circumstances. There’s a palpable sense of panic in the government as to who will betray them next. (Atwood’s gift for basing fiction on historical episodes is in full display here as she transplants the murderous and paranoid atmosphere of the Stalinist Soviet Union into the novel). Feverish mole hunts occur. Biblical passages are still used to justify such violence, but the perception is that the old fervor is gone.

This anger has reached the class of women known as the Wives, already enraged at the Handmaids who lay on top of them as part of an Old Testament ritual—a ritual of mechanical intercourse by the Commanders, culled from the biblical figure Rachel and her handmaid Bilhah. The Wives have become unhinged to the point of murdering other Wives.

To provide this wider scope, Atwood uses three characters, each presented in first person. One is Daisy, a young girl raised by foster parents in Canada. Another is Agnes, who lives in Gilead. And then there’s Aunt Lydia, the kapo who in the first book literally beat the feminism out of prisoners and is now famous enough to warrant a statue of her likeness.

Agnes, although more outwardly rebellious than Offred, doesn’t really offer anything new; Daisy even less so. Raised in the democracy of Canada, she is little more than expletives and colored hair. But in the character of Aunt Lydia, Atwood soars. As viewed by Offred, she was little more than a Bible-spouting thug. Now allowed a first-person voice, she is much more complicated. The reader will learn that, ironically, Lydia was once a lawyer and judge who championed women’s rights.

As with Offred, Aunt Lydia too writes to future generations. Her letters in this regard constitute the best parts of the novel. Sitting alone in a library forbidden to males, she is brutally honest about how she served the regime to save her skin and is now corrupted by it:

I’ve become swollen with power, true, but also nebulous with it—formless, shape-shifting. How can I regain myself? How to shrink back to my normal size, the size of an ordinary woman?

Lydia is as hollow as the men of the first novel. But she is also as self-justifying as an ex-Nazi, stating that future generations shouldn’t judge her harshly, as they weren’t presented with the stark choices she was. Without giving too much away, Lydia is angered by the corruption in the regime and wants to expose it—not just in print but in actions.

Atwood’s gift for irony is in full display as she shows how women are able to use the regime’s ideology against their male leaders. In this case it’s the “separate sphere,” a concept that has its roots in the male society of the nineteenth-century United States. Their purpose was to keep women in the home, justified by the paper-thin notion that women have a superior morality to impart to their children.

Lydia uses this concept of higher morality to help Agnes escape marriage to a Commander (the Commander in question murders his Handmaids). She does so by asserting that Agnes must follow the “higher calling” of being an Aunt.

Another neat bit of irony is that the very Bible Gilead uses to justify its power can potentially contain the seeds of the regime’s destruction. This occurs when the female subjects risk torture and death by breaking open the lock boxes where men keep their Bibles. Agnes concludes that the Handmaids and Aunts have been lied to, and realizes why the “kinder, gentler” New Testament rather than the angrier Old Testament is not an ideological foundation of the regime.

However, the novel flounders by not presenting an atheist or agnostic character or even a mild supporter of the separation of church and state. Seventh-day Adventists, fervent supporters of this concept, are kept offstage and only mentioned when they’re murdered by the regime. Agnes and Daisy engage in a debate about religion but neither of them entertains the possibility that religion should be kept out the government, or vice versa. Even [major spoiler alert!] Aunt Lydia, sickened by the regime to the point of cataloguing its murders and smuggling the intel to the Canadians, does so because Gilead isn’t living up to its founding principles.

Those wanting Offred as a main character will be disappointed. Nevertheless she is a looming presence on almost every page and key to the plot. Atwood does answer whether Offred escaped from Gilead or not. And readers hoping for a novel in which Gilead self-destructs will have to wait for another sequel, for Atwood shows a regime dying by inches. This is a neat trick—keeping the reader hooked while the bad guys slowly rot—and, as usual, Atwood pulls it off.

Read carefully, The Testaments, with its upbeat ending, could provide inspiration for those horrified by the anti-feminist nature of the real US government of today, including the anti-Trump feminists who don the garb of the Handmaids when protesting. If Trump embodies Gilead for them, then he too shall pass.