Converting the Nones: Why an Aware Homo Secularis Is Paramount

Researcher Barry A. Kosmin is the founding director of the Institute for the Study of Secularism in Society and Culture (ISSSC). He coined the term “nones” to describe those who, when asked their religion or religious affiliation, respond “none”—or, if asked to pick from a list on a survey, check “none of the above.” It’s a staple question on the American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS), for which Kosmin has served as a principal investigator since its inception in 1990. He’s also done national social surveys of religious (or irreligious) identity in Europe, Africa, and Asia and is a research professor of public policy and law at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut.

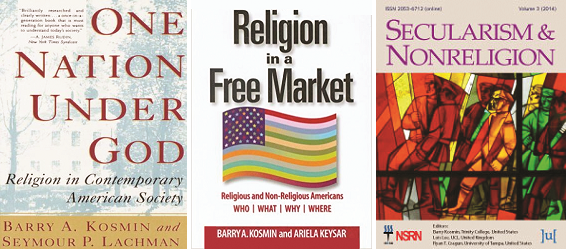

Kosmin was the founding editor of Secularism & Nonreligion, the world’s first journal dedicated to the investigation of secularism and nonreligion in all forms, and he is a former joint editor of the journal Patterns of Prejudice. His books, based on ARIS research, include One Nation under God: Religion in Contemporary American Society and Religion in a Free Market: Religious and Non-Religious Americans.

Kosmin was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award by the American Humanist Association at the AHA Annual Conference at the University of Miami on June 9, 2019.

I AM VERY GRATEFUL to the AHA for honoring me with their Lifetime Achievement Award.

My claim to fame is directing the American Religious Identification Survey series for three decades. These large-scale representative national samples identified and documented the rise of the nones, those Americans who identify with no religion. This irreligious segment of the adult US population has risen more than 300 percent over the past three decades from 7 percent in 1990 to 23 percent today. The rise of the nones has been the most statistically significant trend in American religion, occurring in every state of the Union and among African Americans, Asian Americans, Hispanics, and whites.

So, how and why did we come up with the unusual but now accepted name “nones” for what religionists used to call the “unchurched”? In most religion research prior to the ARIS series, the usual practice was to use questionnaires with a list of religious groups. The form provided a list of religious groups to choose from, and at the bottom was a category for the benighted folk labeled “None of the above.” We did away with the list and instead offered an open-ended question: “What is your religion, if any?” Then we classified all those who didn’t provide a religious identification or who provided a nontheist response as “nones.” This provided amusement because of its satirical association with Catholic sisters. (Nones also had a possible variant pronunciation, an allusion to Monty Python’s Spamalot via Shakespeare: “Hey, Nonny, Nonny!”)

So, how and why did we come up with the unusual but now accepted name “nones” for what religionists used to call the “unchurched”? In most religion research prior to the ARIS series, the usual practice was to use questionnaires with a list of religious groups. The form provided a list of religious groups to choose from, and at the bottom was a category for the benighted folk labeled “None of the above.” We did away with the list and instead offered an open-ended question: “What is your religion, if any?” Then we classified all those who didn’t provide a religious identification or who provided a nontheist response as “nones.” This provided amusement because of its satirical association with Catholic sisters. (Nones also had a possible variant pronunciation, an allusion to Monty Python’s Spamalot via Shakespeare: “Hey, Nonny, Nonny!”)

In my opinion it’s important for activist humanists and secularists to be knowledgeable about the trends in American religion since these account for much of the current polarization in our society. To begin with, you need to distinguish the different aspects of religion: belief, belonging, and behavior. The data shows membership in religious organizations has declined more than belief in the supernatural. As a result, not all those we categorize as nones are nontheists in terms of belief. Moreover, we have to remember that religion is a familial and social activity. Nobody wants to upset their relatives more than is necessary, especially elderly folk who might include you in their will. So, a lot of nones tag along to religious events to show solidarity and keep the peace. Nevertheless, there is a clear generational erosion in organized religion, particularly as tales of clergy scandals, moral corruption, and politicization have alienated many adherents. Fewer people among the younger generation claim a religious identification and fewer children today are receiving religious education and socialization.

But this doesn’t mean we should indulge in triumphalism. The move into the “none” category has largely been a spontaneous and leaderless development. This mass exit from religion is a great opportunity for organizations in the secular movement, but the continuation of the current trajectory and its permanence is not assured. My goal here is to provide you with a realistic appreciation of the forces at play.

We need to produce individuals and leaders with a broad and deep sense of humanist politics and culture, especially of humanism’s achievements in the world—not just in Western culture and history.

The losses suffered by organized religion have occurred largely because of the defection of its nominal and liberal elements. Somewhat surprisingly, the denominations that have suffered the largest losses in members are the more liberal, moderate groups, particularly once socially dominant Mainline Protestants—the Episcopalians, Presbyterians, Congregationalists, and American Baptists. In fact, the trend today is for religious groups not to publicly disparage each other’s differing revelatory truths. So, paradoxically, many of the bitter battles of today’s culture war tend to be internal within each faith or denomination—reformers and liberals versus conservatives and fundamentalists. The focus of these conflicts is usually about control and policy. Since many groups have lost their liberals to the nones the ironic result is that the majority of churches and denominations have become more traditional and conservative.

This is true for Protestants, Roman Catholics, and Jews. For example, this year the United Methodist Church has become the first mainline denomination to reject LGBTQ clergy and gay marriage. The UMC is a global church now dominated by a coalition of white American conservatives and Africans, unafraid to voice strong homophobic and misogynistic opinions. The religious and ideological opponents of humanism are not confined to white American evangelicals.

Islam poses similar challenges to progressives who wish to valorize multiculturalism, indigenous cultures, and people of color. The religious right is dominant globally and across religions and cultures in the Middle East, Africa, and India, and religious intolerance and fundamentalism are growing even among the Buddhists of Burma and Sri Lanka. However, in the US, paradoxically, there is now greater ecumenism among the religious right than ever before. Mormons, Catholics, Evangelical Protestants, and Orthodox Jews no longer dispute their various truths about salvation but instead willingly cooperate on conservative political and public policy issues. For example, American evangelicals who in the 1960s feared the Catholicism of President John F. Kennedy nowadays enthusiastically endorse Catholic justices for the Supreme Court.

One feature of the religious right that is often ignored by humanists is their investment in formal and informal education. They’re not just educating and indoctrinating their young in so-called Christian, Catholic parochial, and Jewish day schools. They’ve also funded universities, law schools, think tanks, and cable television channels. They’ve likewise invested big time in educating adult members in their theology, what I would categorize as their ideology. As a result, their people are well versed in their sacred literature. This is not just a Sunday activity—Wednesday night is church night in much of the American South. The result is that the followers of the religious right are not only actively committed to their cause but also generous, as demonstrated by their churches’ fundraising success, often through tithing.

I bring this to your attention because of the contrast with the situation of contemporary American humanism and secularism. Unfortunately, secularists haven’t invested in formal or informal education to any extent. There are hundreds of theology departments and departments of religion at the country’s institutions of higher learning. Add to that the seminaries that have trained the country’s 300,000 active clergy. The study of secularism includes our lonely and underfunded research institute in Hartford, a minor in secular studies at Pitzer College, and a chair in atheism at the University of Miami. In fact, my own institute is about to close because its funding has ended. The lack of a comprehensive educational network is a disadvantage for secularists in the battle of ideas. There is little hope of missionizing the vast potential population of nones. One cannot rely on the public school system and the universities to guide them towards an appreciation of the secular Enlightenment. The reality is that the Texas School Board has much more influence than the American Humanist Association on the curricula of the nation’s public schools.

It requires some knowledge in order to self-identify as a humanist, atheist, or agnostic. This lack of education is the reason why less than 10 percent of nones actually self-identify with a specific nontheistic identity. Most nones have not been exposed in a systematic way to rationalism and naturalism so they’re left in a void of indifference. The ignorance of the majority of these casual and complacent nonbelievers poses a significant danger because their distancing from religion may only be temporary.

The information gap between religious and secular organizations is vast. The religious have invested heavily in market research on their adherents, not only through their own religious bodies but also with the aid of sympathetic wealthy partners such as the Lilly and Templeton foundations. Again, by way of contrast the secular movement has made minimal investment in market research.

The reason, of course, for the weaknesses I’ve highlighted is that the secular and humanist movements lack resources and therefore institutional infrastructure. It’s a chicken-and-egg problem. Whereas organized religion affiliates a high proportion of its potential constituency (over 100 million Americans are paid-up members of religious congregations), all the secular and humanist organizations combined currently have little more than 100,000 members out of the national population of around fifty million nones. The funding resources and political clout of the two ideologies reflect these membership statistics more than they do those provided by social surveys of religious identification. The religious organizations have the advantage of millions of donors motivated by the powerful eternal reward-punishment myth, an idea with which humanists cannot compete.

Permanent success necessitates creating a social movement with strong institutions having adequate financial resources. Without those solid foundations, the much-heralded rise of the nones could be an ephemeral phenomenon.

Thus, although the secular trend in society seems hopeful in terms of raw statistics, severe challenges face those organizations that would hope to benefit from the trend of disaffiliation from religion. One should be aware of the overconfidence and wishful thinking of pundits. One issue of concern is the emergence of the fashionable “spiritual but not religious” (SBNR) identity. In a 2017 Pew survey on attitudes towards spirituality and religion across fifteen Western countries, 64 percent of SBNRs said even though they didn’t believe in God as described in the Bible, they believed in a higher power. This outlook tends to develop into a search for practices that help the individual achieve a sense of union with the transcendent. It’s not surprising, then, that yoga, meditation, crystal healing, horoscopes, psychics, and sundry New Age beliefs have been gaining in popularity, particularly among the millennial generation. The media tends to encourage this fascination with unreason, the weird, and “woo.” And some neuroscientists now suggest that humans have a built-in need for trancelike emotional states that have been the stock-in-trade of organized religion for thousands of years.

To be a real force in American society, the secular movement needs to create mechanisms to encourage a positive attachment to humanism. Going forward it cannot just rely on the public’s negative sentiment about religion or anti-clericalism. There is a need to overcome intellectual anomie and get the nones to understand and appreciate the cultural inheritance of humanism and freethought and so inspire a positive secular loyalty. Lack of exposure to the intellectual and historical origins of humanism and secularism—to thinkers such as Lucretius, Francis Bacon, Voltaire, Bertrand Russell, Daniel Dennett, and so on—produces what Marxists would define as a lumpen quality to the fast-growing none population. It is a population that lacks self-awareness and solidarity. Though people are under no obligation to be logical or consistent in their attitudes and opinions, one can hope that exposure to reason and science can assist critical thinking. Our research findings show that considerable numbers of nones accept the science of climate change but not vaccination. They believe in evolution and natural selection but also in the power of crystals and homeopathy. So, I would caution you against encouraging platforms that oppose rationality.

History teaches us that social trends aren’t linear and reason isn’t a force of nature that inevitably overcomes superstition. For example, Thomas Jefferson expected that Unitarianism would become the prevalent stream in American religion. If, as I believe, we have a mass of the populace who believe in nothing, then the danger is they will fall for anything unless they’re educated in humanist values and ethics. This is especially important in a time of historic confusion.

AHA Board Member Juhem Navarro-Rivera (right) presents the 2019 Lifetime Achievement Award to Barry Kosmin (left) at the AHA Annual Conference in Miami.

Our greatest need then is to create an aware homo secularis, with a rigorously rationalistic and atheistic point of view and a commitment to church-state separation. We need to produce individuals and leaders with a broad and deep sense of humanist politics and culture, especially of humanism’s achievements in the world—not just in Western culture and history. The hurdles in forming a new mass identity for the humanist and secular movement are formidable at present because of its lack of embedding in social networks. Social trends could be reversed if we fail to educate the indifferent masses of nones, the millions who have lost religion but have found no replacement belief or value system. Unless we create a new world of meaning for them, we could face an analogous situation to that described by Rebecca West in 1930s Europe—the allure of fascism “to the mindless, traditionless, possessionless.”

At this moment it’s crucial for us to remember that the humanist movement is based on optimism about the human condition and the idea of progress. Obscurantism, anti-intellectualism, fearmongering, and spreading doom and gloom are bad and dangerous ideas. Making people anxious with apocalyptic prophecies about acknowledged problems such as radiation, GMOs, and climate change makes people more likely to turn to individuals and groups offering certainty and external supernatural assistance. One of Paul Kurtz’s “Affirmations of Humanism” is: “We believe in optimism rather than pessimism, hope rather than despair, learning in the place of dogma, truth instead of ignorance, joy rather than guilt.” These ideas are the polar opposite of the warning in the title of his 1999 book, Fears of the Apocalypse: The Escape from Reason. Humanists have to have faith in ability of the human intellect to solve problems because we believe that the unknown is knowable. We have to valorize the collective intelligence, wisdom, and knowledge of the human species and the value of advances in science and technology. Both secular and scientific values were entrenched within the Enlightenment project of emancipating humanity and actualizing the highest human potentials through diffusion of knowledge. These goals, in turn, became linked to the quest for liberty, freedom of thought, and popular sovereignty, and thus democracy. The triadic relationship of humanist values, scientific literacy, and social and economic progress must remain the “worldly” focus of our struggle today.

Humanists have a duty to counter the current powerful cultural narrative of negativism and pessimism, which maintains that for decades now the world has been in a state of escalating crises, decline, and suffering. That vision, along with original sin, is the stock-in-trade of religious fundamentalism and messianic thought. In fact, as Steven Pinker (Enlightenment Now) and Michael Shermer (Heavens on Earth: The Scientific Search for the Afterlife, Immortality, and Utopia) have explained in their recent books, we live in good times. The present might not be perfect, but the good old days were dreadful. Most of you reading this live much more pleasant and longer lives than your ancestors thanks to the innovations brought about by the human-produced scientific and medical advances and the political and social revolutions of the past three centuries.

Finally, my evidence-based assessment is that the secular movement needs to consolidate and build upon contemporary, fortuitous trends. Relying on the courts and careerist politicians to help deliver your social and political agenda may not guarantee success. Instead, humanists and secularists need to copy the successful organizational strategy of the religious right. The movement has to offer a clear, positive, alternative narrative based on a sustained educational program aimed at mobilizing a mass public. Permanent success necessitates creating a social movement with strong institutions having adequate financial resources. Without those solid foundations, the much-heralded rise of the nones could be an ephemeral phenomenon.