Musings of a Solo-ist Astrophysicist

The following is adapted from Neil deGrasse Tyson’s June 5, 2009, speech in acceptance of the American Humanist Association’s Isaac Asimov Science Award, presented to him at its annual conference in Tempe, Arizona.

When I was invited to come to the 2009 Annual Conference of the American Humanist Association, I was told I would be receiving the Isaac Asimov Science Award, and I noticed that this one award does not have the word “humanist” in it. All the other awards given out by the AHA do—the Humanist Pioneer Award, the Humanist Heroine Award, and, of course, the Humanist of the Year Award. And I’m good with that because I never really wanted to be an “-ist” (or an “-ism” for that matter).

When I was invited to come to the 2009 Annual Conference of the American Humanist Association, I was told I would be receiving the Isaac Asimov Science Award, and I noticed that this one award does not have the word “humanist” in it. All the other awards given out by the AHA do—the Humanist Pioneer Award, the Humanist Heroine Award, and, of course, the Humanist of the Year Award. And I’m good with that because I never really wanted to be an “-ist” (or an “-ism” for that matter).

I am a scientist—more specifically an astrophysicist, so those are the only -ists I’ll take. Because what worries me is the moment one is announced as an -ist—the moment that comes up in a conversation—the person with whom you are conversing establishes an entire philosophical worldview for you before any more words are exchanged. Now, if they are opposed to that -ism, you’re already in a hole in the conversation that you have to dig out of. The remarkable thing, of course, is that humanism is perhaps the most diverse -ism out there. For example, you have theologians who are part of this movement. That’s kind of interesting. Yet you don’t have atheists who are part of the fundamentalist religious movement. It just doesn’t work.

I prefer to enter a conversation with a fresh start. When the beginning is pure, seeds get planted; plants germinate and grow. But here is what’s interesting. Out of everything I’ve written in my life, only two essays at all address God or spirituality; everything else is just simply about the universe. But those two essays get remembered most. One of them sharply criticizes the intelligent design movement, not by saying it should be banned but by declaring that it doesn’t belong in the science classroom. This sentiment became associated with the atheist movement. Sometime later I stumbled upon my Wikipedia page, and what’s spooky is that my wiki page is more up-to-date than my personal home page. For example, two days after I appeared on the Daily Show with Jon Stewart I thought, let me add that to my wiki page. I went there, and the link was already up. (The days of anonymity are long gone.) So I’m looking at the page and it says, “Neil deGrasse Tyson, a long-time atheist…” and I thought, where did that come from? I never said that. So I removed it and I put in “agnostic” because I think, based on all the folks who are agnostic historically, I come closer to the behavior of an agnostic than the behavior of an atheist. Three days later it was back to atheist. Then I learned that there are people who want to equate agnosticism with atheism. So I went back in, thinking I needed to be clever about this, and I changed the phrase to: “widely claimed by atheists, he is actually an agnostic.”

Another related incident happened recently, this time on my Facebook page. I put in a note about what I was doing at the time, to let everybody know all my business. (Was it not just five years ago you didn’t tell anybody anything about your life, and now everybody knows everything? When did that happen? Did I miss that memo?) I was in Florida at Cape Canaveral watching the shuttle launch to service the Hubble Telescope; a beautiful launch, beautiful weather, beautiful fix-it mission, and everybody came back safe. So after liftoff, I wrote “Godspeed shuttle astronauts.”

Another related incident happened recently, this time on my Facebook page. I put in a note about what I was doing at the time, to let everybody know all my business. (Was it not just five years ago you didn’t tell anybody anything about your life, and now everybody knows everything? When did that happen? Did I miss that memo?) I was in Florida at Cape Canaveral watching the shuttle launch to service the Hubble Telescope; a beautiful launch, beautiful weather, beautiful fix-it mission, and everybody came back safe. So after liftoff, I wrote “Godspeed shuttle astronauts.”

Now, let’s give this some context. In 1962 John Glenn went into orbit and returned to the banner headline on the New York Daily News, “Godspeed, John Glenn.” That phrase is cultural within the aerospace community. You say it like you are saying hello; someone’s going into orbit, into space, you say Godspeed. You’re doing something at the edge of our technology—Godspeed. You even say it for test pilots.

So I entered it onto Facebook and within minutes one person commented, “Godspeed? I thought he was an atheist.” Then I had the defender: “No, he’s clearly an agnostic. It says it over here on the profile page.” I had to jump back in, and I said, “If you’re religious, this word means something religious to you. If you aren’t, it simply means successful mission, come back safe.” So I will not deny myself access to vocabulary because some people see it as religious. Surely there are atheists in the world who have used the word goodbye, which means “God be with you.”

I’m honored when those among us see my work and analogize me to Carl Sagan, who put science literacy on the map and started a national dialogue about what we know and don’t know of the universe. And he did it with both passion and compassion. There is a difference, though, between Carl Sagan and me. That difference—and I’m embarrassed to say this—is that I do not have the energy to debate people whose brains are tangled messes of irrational thoughts. So you have never seen me debating a UFO person, a religious fundamentalist, or a crop circle person. In fact, a year ago I spoke at TAM 6 (The Amazing Meeting) in Las Vegas. I was honored to have been invited but that was my first time ever speaking to a skeptic community. This doesn’t mean I don’t relate. I was practically a charter subscriber to the Skeptical Inquirer and have even contributed to it. But my energy to enlighten is principally directed at trying to get people to think straight in the first place rather than to undo the tangled mental pathway later on.

So here is my pact with you. I will do my damndest to get them thinking straight up front but if I fail, I’m handing them over to you. So thank you for this award and thank you for your warm reception. Now, I just want to have a conversation about life, the universe, and everything else.

[The following are Neil deGrasse Tyson’s responses to questions that were posed by conference attendees and that are briefly summarized here.]

Neil deGrasse Tyson on the Grand Canyon and creationist books that give it a non-evolutionary explanation:

Where I work in New York at the Rose Center for Earth and Space at the American Museum of Natural History, there is a huge exhibit on the Big Bang. Occasionally, someone walks up and says, “You make no mention of God in there, why not?” I respond by suggesting, “Why don’t you go to the exhibit on human origins first and then come back to us.” And then they never make it back because they have skeletons of monkeys holding hands with people over at the human evolution exhibit hall. It’s clear that biological issues are of much greater significance to the religious community and an affront to their belief system than the Big Bang because they just never make it back.

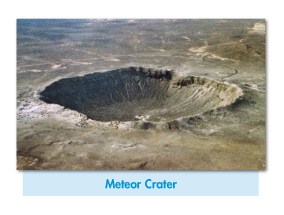

If I were going to visit the Grand Canyon I’d make a detour and visit Meteor Crater because however long you think it took to make the Grand Canyon, it took a tenth of a second (or less) to make Meteor Crater. An asteroid the size of our planetarium slammed into earth going ten miles per second and left a hole in the ground sixty stories deep and practically a mile across. In a tenth of a second. Falling from the sky. When I was fourteen years old, I made my first trip to both. I looked at Grand Canyon; okay, it’s kind of nice. I went to Meteor Crater and could not speak just realizing how quickly that hole got made and how susceptible we are as little squishy human beings walking on the earth’s surface. So people will say what they want or believe what they want; I will just simply say keep nonscience out of the science classroom, and that is all.

If I were going to visit the Grand Canyon I’d make a detour and visit Meteor Crater because however long you think it took to make the Grand Canyon, it took a tenth of a second (or less) to make Meteor Crater. An asteroid the size of our planetarium slammed into earth going ten miles per second and left a hole in the ground sixty stories deep and practically a mile across. In a tenth of a second. Falling from the sky. When I was fourteen years old, I made my first trip to both. I looked at Grand Canyon; okay, it’s kind of nice. I went to Meteor Crater and could not speak just realizing how quickly that hole got made and how susceptible we are as little squishy human beings walking on the earth’s surface. So people will say what they want or believe what they want; I will just simply say keep nonscience out of the science classroom, and that is all.

My book Death by Black Hole, in spite of that title, is really about how science works and it is the full expression of everything I know about how the frontier of science moves forward, including occasions that interfere with it and that propel it. It’s a very candid assessment if you need some ways to think about science and its relationship to our understanding of the cosmos.

…on the absence of Pluto in Gustav Holst’s seven-movement orchestral suite, The Planets:

Holst ascribed a movement to each of the classical post-Copernican planets: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. He wrote it in the 1910s and excluded Pluto because it hadn’t been discovered yet. That would have been a clairvoyant movement if he had. Once Pluto was discovered he was invited to write a movement on Pluto. He actually began it but then came down with pneumonia and chose not to finish. In the 1990s a Holst scholar composed a movement for Pluto in the style of the other movements. But now Pluto isn’t a planet, so no one listens to it anymore.

Other things like that changed when Pluto was reclassified as a dwarf planet in 2006. The Adler Planetarium in Chicago was founded in 1930 about a month before Pluto was discovered. The foyer features relief plaques, each one representing one of the eight planets in the solar system. Then Pluto was discovered and they were stuck because it didn’t fit. Now that Pluto’s not a planet it’s right back in style.

… on the theory that the universe is expanding and what dark matter and the Big Bang have to do with it:

The only evidence we’ve ever had on what the universe is doing has told us that we are expanding. What we discovered in 1998 was this mysterious pressure in the vacuum of the cosmos that is operating against the natural efforts of gravity and is accelerating the expansion. So we’re not only expanding, we are accelerating in our expansion. We blame that on dark energy. Now, we have no clue what dark energy is but we measure its existence, and that is why we speak of it as a real thing. We call it dark energy but we could just as easily have called it Fred. The same is true of dark matter; 85 percent of all the gravity we measure in the universe is traceable to a substance about which we know nothing. We can call that Wilma, right? So one day we’ll know what Fred and Wilma are but right now we measure the distance and those are the placeholder terms we give them.

People ask if the Big Bang was perhaps not just a single moment, but a continuous process that’s pushing the universe apart. But the signature of the Big Bang is quite singular. We know what a Big Bang looks like; it’s very hot and matter and energy form a soup of a condition wholly unfamiliar with anything we would see in everyday life. And we don’t see that happening continuously; we only see that happening fourteen billion years ago. As we look out in space we see things not as they are but as they were, given the time it has taken light to reach us. So I don’t see you in the front row as you are, I see you as you were twelve nanoseconds ago—twelve billionths of a second ago—the time it takes light to reach me. So if I put you out halfway across the universe, you’re not even born yet.

…on the danger to a person standing on a planet, looking out at another planet that’s been swallowed by a black hole (as happens in the latest Star Trek movie):

It’s definitely dangerous for people on the swallowed planet. Let’s establish that fact up front. Now, black holes have very high surface gravity but their total gravity is unchanged, so if the sun were to become a black hole we would still orbit it in a year and nothing would change for us. The sun’s mass would not increase. In Newton’s Law of Gravity all that matters is how far away you are from the center of that object and what the mass is of you and that object. That’s it. So if a planet turns into a black hole, it has the same mass. It’s just really, really small and so it has really high gravity. It would be a spectacular sight, but bad for the residents of the black hole itself.

…in response to an audience’s member’s question, “What’s the edge of the universe like?”:

You ask me as though I’ve been there! Where the actual edge of the universe is, if there is an edge at all, is unknown to us. The horizon is just a limit to where light has been travelling over the lifetime of the universe itself, fourteen billion light years’ distance. Anything fifteen billion light years away isn’t old enough for us to even see the light that has emerged from it, so it remains invisible to us until a billion years go by. We are at the center of our own horizon just as a ship at sea is in the center of its own horizon. If there is an edge, we don’t know about it and many people assume the universe is infinite. But it’s an assumption, not a requirement.

…on the opinion (that runs contrary to the position of the Planetary Society) that Mars missions should be robotic only because it’s too impractical and dangerous to send humans:

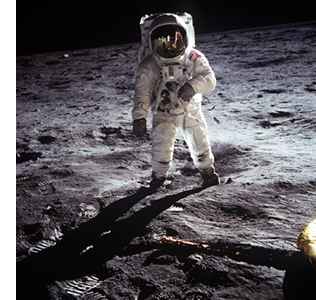

In my advancing years, I have become rather pragmatic. I have come to recognize some fundamental truths about human behavior. I wish it were different but it’s how it is. And how it is, is that nobody names schools after robots. Nobody has ticker-tape parades for robots. It just doesn’t happen. There were robots in the 1960s. There was a rover on the moon. Nobody cared because astronauts were on their way. The moment a human being advances a space frontier, everybody talks about it because that person risked his or her life. (We are not risking their life; they are risking their life.)

In my advancing years, I have become rather pragmatic. I have come to recognize some fundamental truths about human behavior. I wish it were different but it’s how it is. And how it is, is that nobody names schools after robots. Nobody has ticker-tape parades for robots. It just doesn’t happen. There were robots in the 1960s. There was a rover on the moon. Nobody cared because astronauts were on their way. The moment a human being advances a space frontier, everybody talks about it because that person risked his or her life. (We are not risking their life; they are risking their life.)

And the history of human culture, for whatever reason, values the efforts of those who risk their lives for discovery. Statues are built to them; they get remembered forever. And so there is an aspect of space exploration that goes beyond scientific discovery and captures the essence of exploration that has driven human beings in the history of our culture beyond the limits previously set by others. And that enterprise is what the nation buys into. That enterprise is what stimulates the interest and the urge to move a frontier out.

And so I can tell you that my fellow astrophysicists sincerely believe that NASA is their private science funding agency. When NASA decides to spend money on a manned program, they will cry foul. But ask yourself, why was NASA founded? It was founded in response to Sputnik and a geopolitical war we felt we were losing. Not only that, over the past fifty years only about 23 percent of the total budget for NASA has gone to science. The rest has gone to the space station, the shuttle—all the manned programs.

In fact, scientific discovery is the tail of a much larger dog. Darwin didn’t say, “I need a boat to go to the Galapagos, let me hire one.” No, the boat had another agenda and he piggybacked along. Somebody else wrote that check. Captain Cook goes to the South Pacific. Why is he going? As we read it, he wants to measure the transit of Venus across the surface of the sun. It only happens every few hundred years and if measured accurately, you get the scale of measurement in the solar system. We didn’t know the distance from the earth to the sun until that expedition. But wait, who wrote that check? England wrote that check. Did they really care about how far the earth was from the sun? Consider what happens a few years after Captain Cook comes back—England takes control of the South Pacific. England takes control of Australia. England rules that entire quadrant of the world. That is who wrote that check.

So let’s be honest with ourselves about what enables science. It has never been science. It has been politics. It has been war. It has been economics. And I have come to recognize that fact. And so I could say let’s just do the science with the robots. But we will lose the budget because the budget is driven by the manned program and the science, for better or worse, must piggyback that.