Remembering Lewis Hine

“Kindly, trustful, wistful, amazingly innocent, his front is a mask for his power. He looks like an unworldly schoolteacher, needing protection from the rigors of the everyday world. But behind this disarming apparent naïveté is an artistry and directness and determination that has etched the history of an era into the consciousness of the country.”

— Robert W. Marks,

“Portrait of Lewis Hine,” Coronet, February 1, 1939

Lewis Wickes Hine was born in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, in 1874. While studying at the University of Chicago he met Frank E. Manny, who was the superintendant of the Ethical Culture School in New York City. In 1901 Hine moved to New York and became a teacher at the school, which was founded by Felix Adler, himself a social reformer who influenced modern Jewish humanitarianism and started the Ethical Culture movement. The school was originally called the Workingman’s School, and was intended as a free kindergarten and elementary school for poor children. By the early 1900s the student body had grown to include upper-class students as well. The Society of Ethical Culture took on its sponsorship and saw to it that the school embodied its principles of transforming society through moral education based on humanist values, with no adherence to any sectarian creed.

In 1904 Hine, by then a geography and nature instructor, and Manny created the nation’s first photography program at the Ethical Culture School. Equipped with a camera, Hine took students out of the classroom and into the countryside to photograph nature, but he also took them into the streets and tenements of New York City to photograph its populace. Hine also began capturing the faces of immigrants from Ellis Island in a series of moving and respectful photographs that were in stark contrast to the media’s often negative depiction of them.

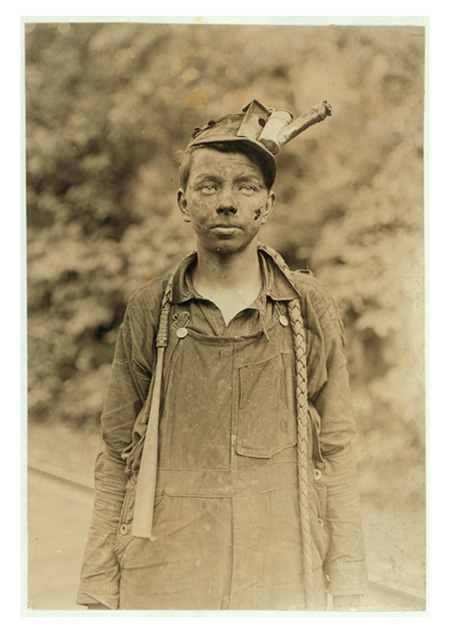

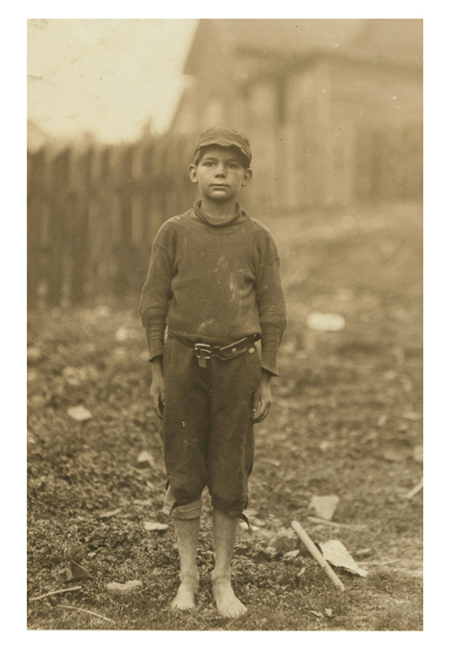

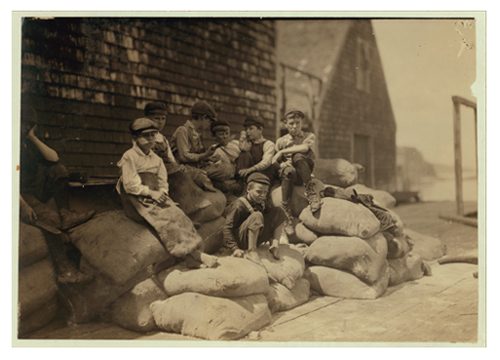

In 1908 Hine took a position for the National Child Labor Committee (formed in 1904 to abolish child labor) and set out on the road leaving his wife Sara Ann and infant son Corydon at home. Hine traveled over 12,000 miles, taking photos of child laborers in factories, fields, and mines. He kept a small notebook in his pocket, and once out of the sight of overseers, he asked the children questions, jotted down their answers, and took their photos. Hine assessed the children’s height in proportion to the buttons he had measured on his jacket. The children, though frequently cautious, must have sensed Hine’s good intentions as they opened up to him and shared bits of their lives.

Hine’s captions were often as evocative as his photographs:

Freddie Kafer, a very immature little newsie selling Saturday Evening Post and newspapers at the entrance to the State Capitol. He did not know his age, nor much of anything else. He was said to be five or six years old.

Seven-year-old Ferris. Tiny newsie who did not know enough to make change for investigator.

Furman Owens, twelve years old. Can’t read. Doesn’t know his ABC’s. Said, “Yes I want to learn but can’t when I work all the time.”

Neil Power, ten years old, he said, “Turns stockings in Rome Hosiery Mill.” A shy, pathetic figure. “Hain’t been to school much.”

Hine’s photographs and narratives told of the children’s physical and emotional abuse, their exposure to physical hazards and the dangers of the red-light district, including smoking, alcohol, and prostitution. He gave voice to the children forced into labor before many of them could even tie their shoelaces, recite the alphabet, or spell their own name. His work stirred the public conscience and undeniably contributed to the eventual passage of child labor laws.

Hine later went on to work as a photographer for the American Red Cross, documenting relief work in Europe during and after World War I. In 1930 he was chosen to document construction of the Empire State Building. While his earlier work had often revealed the stark, even ominous side of labor and progress, these photographs celebrated the proud post-war American workforce while also depicting steel workers in perilous positions. (An iconic image from this collection shows eleven construction workers casually eating lunch while perched upon a girder high above Manhattan.) Hine later covered various aspects of the Great Depression and in 1936 was selected as the photographer for the National Research Project of the Works Projects Administration, but his work there was never completed. The last years of his life were a struggle due to loss of financial support both from government and corporate sponsors. He ultimately lost his house and applied for welfare. Hine found himself as destitute as the children and adults he once captured on film. He died in the autumn of 1940 at age sixty-six.

Hine once said, “There are two things I wanted to do. I wanted to show the things that had to be corrected. I wanted to show the things that had to be appreciated.” That he captured the harsh conditions in which his subjects lived and worked was notable, but that he showed their beauty and resilience was remarkable, and his body of work turned the forgotten into the unforgettable.

I was only a year or two beyond childhood myself, searching out the work of Dorothea Lange and Margaret Bourke-White in our small town’s public library, when I discovered Lewis Hine’s powerful work. The black-and-white photos of children were particularly riveting—the barefoot, scruffy kids in ragged clothes, whose darkly luminous eyes pierced the haze of the factory light, were incredibly vibrant on the page—transcending time and medium.

Later, as a college student working with migrant children and then as a social worker for Washington State Child Protective Services, I saw those child-laborer faces come to life in the children I worked to help or protect. By turns, the faces were spirited, disheartened, jovial, defiant, innocent, or compromised—but never without hope. Throughout the years, Hine’s photographs were never far from mind. And today, when treatment of immigrants remains a controversial issue within our borders, and when child laborers worldwide still toil in factories, fields, and sweat shops to provide the clothes on our backs, the dinnerware for our meals, and the toys for our children, Hine’s work is no less relevant. It is in this vein that I was inspired to write the following poems, accompanied by his images.

|

Two Bit I carry words from dawn to dusk |

|

Morning Song The morning papers are heavy Mama fetches me come dark |

|

Glimpse With jagged nails and numbed hands

|

|

|

The Driver I drive a team of mule’s—stabled underground At home, at night—I burn a lantern low I jerk awake with a whoop |

|

|

Neil Power

At work, they ask if the cat’s got my tongue |

FLESH The other guys jabber about baseball

|

|