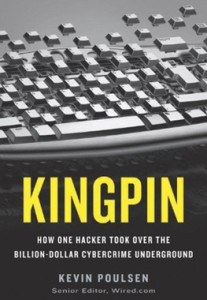

Kingpin: How One Hacker Took Over the Billion-Dollar Cybercrime Underground

Readers of a certain age might remember the “phone phreaks” of the 1960s and ’70s who deviously manipulated telephone technology in order to make free long distance calls, disclose American Telephone and Telegraph secrets and, in general, drive AT&T crazy. In retrospect, those characters seem almost ingenuous and amusing, more interested in relishing their naughty exploits than with mayhem. But there’s nothing childlike or amusing about today’s version of phone phreaks: criminals who, for plunder (lots of it) and other more sinister reasons, ruthlessly and zealously inflict havoc on and through cyber networks. Kevin Poulsen’s new book, Kingpin: How One Hacker Took Over the Billion-Dollar Cybercrime Underground, is a flawed but fraught overview of our current digital underworld, where such vile hoodlums thrive.

Kingpin focuses on the sleazy life of one Max Butler (a.k.a. Max Vision, Iceman, et al. and ad nauseam). Max was born in Idaho to middle class parents in 1973. (A demerit to Poulsen for omitting the year of birth—I had to find it online—and for being rather casual in general about Max’s personal chronology.) By age eight he was a computer geek, and by high school, Max had gone bad. He was sentenced to probation for burglary and other crimes (he stole chemicals from his school), and at the age of eighteen he received his first prison sentence, five years for assaulting a girlfriend. Max served four and was released on probation in 1995. If I were to recount Max Butler’s “career” in detail from this point on, this review would be as long as Kingpin. So I’ll confine myself to some noteworthy aspects of his escapades.

Unlike most ex-cons, Max had a skill: he was a great computer hacker, able to sneak into and wrest control of a wide range of computer systems that didn’t belong to him. He did try to go straight for a while—he became a so-called white hat cyber-informant for the FBI. The bureau sacked Max when it discovered that, while a white hat, he had penetrated a number of government computer systems (some belonging to branches of the armed forces) without permission. He did it mainly to prove to himself that he could. Max eventually pleaded guilty in federal court in 2000 to charges related to his trespassing in the government’s cyberspace. He entered prison in 2001 and served a little more than a year. The breakup between the wizardly hacker and law enforcement was, in retrospect, inevitable: Max found crime a greater turn-on than thwarting crooks. (Those who abhor the FBI because of its bad old days under J. Edgar Hoover might be happy to learn that today’s agency, at least as it’s portrayed in this book, is not a rogue organization: it seems, for instance, to diligently adhere to protocols instituted, presumably, to ensure lawful investigations.)

Once out of prison, Max unfortunately established just how talented he was at outwitting and dominating all manner of cyber-security mechanisms. He hacked banks. He hacked a multitude of businesses via Wi-Fi. He ripped off information other hackers had stolen. In 2005 he established a hackers’ website, Carders Market, that was a buying and selling supermarket for purloined data.

Max’s energy and expertise enabled him to steal an enormous quantity of credit card information; he and his friends then installed the information into new fraudulent credit cards and accumulated money and merchandise. Poulsen’s detailing of their techniques and logistics reveals an impressive enterprise. And a profitable one: when he was riding highest, Max was personally earning a thousand dollars a day.

Eventually, Max wasn’t content to be a mere superb thief; he aspired to be the Don Corleone of cybercrime. In 2006, inspired by a book written 2,600 years earlier, Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, he invaded and eradicated rival hacker websites; as a result, Carders Market added 4,500 new hacker clients (for a total of 6,000). Max had become the star of his realm.

Alas for Max, he wasn’t the only criminal capable of betraying fellow lowlifes. A close colleague, in deep trouble with the feds, ratted out Max to them, and he was arrested in 2007. A team from Carnegie Mellon University, assisting federal authorities, was able to breach the security of Max’s own computer. Poulsen describes Max’s reaction to this incursion: “[I]t felt like an intimate violation. The government was in his head, reading his mind and memories. …he wept into his pillow.” Poor Max was no longer a kingpin, just another criminal defendant confronting a disastrous future. He ended up assisting the government’s inquiry into his criminal deeds; there was much talk about 1.8 million credit card accounts from over a thousand banks and a staggering $86.4 million dollars in fraudulent credit card charges. In 2009 Max pleaded guilty in federal court. He was sentenced to thirteen years behind bars, the longest prison term imposed on a hacker up to then, and ordered to pay $27.5 million in restitution. Max could have received thirty years to life, but the judge and prosecutor believed that he was sincerely contrite.

Alas for Max, he wasn’t the only criminal capable of betraying fellow lowlifes. A close colleague, in deep trouble with the feds, ratted out Max to them, and he was arrested in 2007. A team from Carnegie Mellon University, assisting federal authorities, was able to breach the security of Max’s own computer. Poulsen describes Max’s reaction to this incursion: “[I]t felt like an intimate violation. The government was in his head, reading his mind and memories. …he wept into his pillow.” Poor Max was no longer a kingpin, just another criminal defendant confronting a disastrous future. He ended up assisting the government’s inquiry into his criminal deeds; there was much talk about 1.8 million credit card accounts from over a thousand banks and a staggering $86.4 million dollars in fraudulent credit card charges. In 2009 Max pleaded guilty in federal court. He was sentenced to thirteen years behind bars, the longest prison term imposed on a hacker up to then, and ordered to pay $27.5 million in restitution. Max could have received thirty years to life, but the judge and prosecutor believed that he was sincerely contrite.

Kingpin badly needs a glossary of technical terms. Moreover, crucial parts of the story would have been clarified if the author had cited the federal laws that Max and the other hoods violated, and also if he had probed the FBI and Secret Service’s overlapping spheres of responsibility. (Both agencies investigating the same computer crimes strikes me as a waste of taxpayer money.) Nevertheless, the book is so engrossing and unnerving, its lapses are forgivable. Poulsen, a senior editor at Wired magazine, is, for the most part, a good, conscientious reporter who certainly knows his subject. As well he should: at one time he too was a masterly hacker and in 1994 was sentenced to fifty-one months in a federal prison.

(Incidentally, every criminal hacker I’ve ever heard of has been a male. I don’t know if this is significant, but it’s intriguing.)

Poulsen’s survey of the particulars of hacker methodologies and the hacker subculture provides useful information to honest folks, because it demonstrates just how adept and tenacious computer miscreants are. What Poulsen doesn’t satisfactorily scrutinize is what actually motivates these cybervillains. Poulsen describes Max’s rationale for his behavior this way: “Credit wasn’t real, Max reasoned, just an abstract concept; he would be stealing numbers in a system, not dollars in someone’s pocket. The financial institutions would be left holding the bag, and they deserved it.” Later in the book, Poulsen offers his own interpretation of Max’s criminality: “He’d become addicted to life as a professional hacker. He loved the cat-and-mouse games, the freedom, the secret power. Cloaked in the anonymity of his safe house, he could indulge any impulse, explore every forbidden corridor of the Net, satisfy every fleeting interest—all without fear of consequence, fettered only by the limits of his conscience. At bottom, the master criminal was still the kid who couldn’t resist slipping into his high school in the middle of the night and leaving his mark.”

Poulsen’s explanation comes closer to the truth than Max’s, but he doesn’t take his delineation to its grimly inevitable conclusion. From my reading of Kingpin, it seems clear that Max and the other cyberscum aren’t primarily impelled by Robin Hood delusions, loutish kicks, or even loot. These individuals are ultimately driven by pure malice: they are anomic thugs who cherish destroying—lives, careers, businesses, the “establishment,” society. It is the nihilism goading Max and his ilk, their complete lack of a moral sense, that makes this book not just another true-crime narrative but a horror tale of sorts and a truly terrifying read.

A May 18 Wall Street Journal article stated: “After spending weeks to resolve a massive Internet security breach, Sony Corp. Chief Executive Howard Stringer said he can’t guarantee the security of the company’s videogame network or any other Web system in the ‘bad new world’ of cybercrime. …He warned hackers may one day target the global financial system, the power grid or air-traffic control systems. ‘It’s the beginning, unfortunately, or [sic] the shape of things to come,’ said Mr. Stringer. ‘It’s not a brave new world; it’s a bad new world.’” Dear reader, fellow victims (a few months ago, hackers raided Verizon and stole lots of e-mail addresses, including mine): It’s going to get worse before it gets better. Or maybe it’ll just get worse.