Moving Past a Warm-Up: Is Action to Mitigate Climate Change Possible Today?

Image by © Dmytro Tolokonov | Dreamstime.com

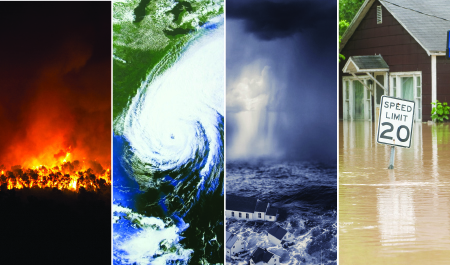

Image by © Dmytro Tolokonov | Dreamstime.com AS THESE WORDS are written, Oregon and Washington State are burning, much of California and Texas are withering without water, Boulder, Colorado, was recently flooded (where I once lived was partly under water), and not long before that Manhattan and coastal New Jersey were inundated by the worst storm surges in their history. Can climate change be blamed for all of these disasters? No. Is climate change likely to have been an underlying cause of some of them? Almost certainly. The situation is filled with ironies. For example, if current changes in atmospheric circulation continue, future mid-latitude summers may become cooler while Arctic temperatures reach record-high levels. The one certainty is that the climate is changing and that much of that change is harmful to human activity.

The first question thoughtful people ask concerns the science of climate change: Do we know the science well enough to be confident that we’ve identified the major cause? We do. And so do most of the well-educated people in the world today, including an overwhelming majority of all scientists, with an almost universal consensus among the climate scientists who actually work on the problem (see the 2013 Science Basis Report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC]). Global warming is the cause of contemporary climate change. We also know that anthropogenic greenhouse gases led by carbon dioxide are responsible for this warming. Thus it is human activity, not some natural process, that’s causing these problems. If we can find a way to substantially reduce the emission of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere due to our technological activities, we will have taken a major step toward mitigating the damaging effects and preparing a better future for those who live on after us.

Most readers know that we have yet to take these actions. It’s natural to ask why, and, again, we know the answer. The simple version is that there are formidable, well-financed opponents of reducing carbon dioxide emissions in the United States today, who fear that the costs of modifying our current energy technologies will reduce profits. Their highly effective promotion of denial and their advocacy for delay have been investigated by many authors. In my opinion the best current summary is the one laid out by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway in their 2011 book, Merchants of Doubt. Their research reveals the methods used by prominent deniers of the best science to confuse scientifically challenged voters—essentially by claiming that there is a major scientific controversy over the causes of climate change, when in fact there is no significant scientific controversy whatsoever.

It is, in effect, a clever sham, first employed by the tobacco industry as the best way to confuse a vulnerable public into opposing any regulation of a major industrial product. The technique has since been used to delay various regulatory efforts, including the regulation of sulfate emissions that cause acid rain, several chemicals responsible for the widening carcinogenic ozone hole, and, most recently, anthropogenic greenhouse gases. Fortunately, the lobbying efforts of these contrarians were eventually overcome in the first three cases to which they were applied, but they have been completely successful to date in preventing national legislation to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. When the record of a very small number of once-distinguished scientists who have argued to block government regulation was examined, Oreskes and Conway noted an almost uniform adherence to a political ideology falling far to the right on the contemporary political spectrum.

There has been some progress. The scientific community at large is becoming increasingly concerned about efforts to distort the public’s grasp of the serious effects of climate change. The reaction of the National Academy of Sciences to the climate contrarians’ attempt to discredit climate science (the Climatic Research Unit email controversy known as Climategate) is encouraging. In a letter sent to Science magazine in May 2009, 255 members of the NAS excoriated the Climategate perpetrators for their “McCarthy-like harassment of our colleagues” and for resorting to “outright lies.” It gives us hope that such scientists have lost patience with those who play by different rules. However, the United States is still far from achieving legislative action on carbon dioxide emissions.

Certain Republican congressmen recently announced a plan to sue President Obama for implementing an Environmental Protection Agency regulation that limits carbon dioxide emissions from highly emitting, often old coal-fired power plants. The right of the EPA to produce such regulation was confirmed by a Supreme Court whose extremely conservative majority has a record of business-friendly rulings. In a more functional and less confrontational political environment than the present one, such a lawsuit would probably be considered bizarre or even ridiculous. This leads us back to the basic question: Is action to mitigate climate change possible today?

Photo credits left to right: © Dugudun | Dreamstime.com, © Vladislav Gurfinkel | Dreamstime.com, © Andrey Kryuchkov | Dreamstime.com, © Tony Campbell | Dreamstime.com

The answer to this question may be yes, but we should understand that the odds are long and the process won’t be easy. When preparing for any major legislative effort a coherent, realistic plan for action must be available. Such a plan has been proposed by William Nordhaus, a well-known economist who is generally well regarded among the more reasonable elements in both the business and environmental communities.

But before launching into a discussion of that plan, it’s worth mentioning an element crucial to any proposal’s legislative success. Each year congressional representatives receive an enormous number of requests from both individual constituents and large collective interests to which they may be beholden. Ignoring constituents’ interests when formulating a proposal is a sure-fire way to have that plan fail.

What should a successful plan address? Recalling that the science is now settled on the major questions, the four aspects of climate science worth emphasizing are:

- Anthropogenic greenhouse gases, especially carbon dioxide, are causing global warming-induced climate change (the five IPCC reports to date illustrate the scientific community’s increasing confidence in this regard);

- The enormous database of observations confirms both global warming and climate change;

- Global climate models are constantly improving and have even provided some recent predictive power; and

- A high degree of agreement exists between actual climate observations and many of the predictions provided by these climate models, an agreement that goes well beyond merely predicting global temperature changes.

The major science on climate change is very secure. Nevertheless, the science alone is not enough to capture the collective conscience of Congress, as recent events have demonstrated. Economics must be combined with the results of the best climate models, incorporating possible economic trends and probable future technological developments into a viable plan for mitigation efforts.

Even when President Obama had Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress from 2009-2010, Congress still failed to pass legislation that would have put a price on carbon dioxide emissions. Too many members of the president’s own party feared that their understandably anxious constituents would reject them at the next election if they supported such legislation, as many voters may well have done. While the economic recession that Obama inherited made his task especially difficult, this failure illustrates that anything less than a major global climate catastrophe is unlikely to shock enough people into supporting wide-scale climate change legislation. Despite this, a plan for climate-change mitigation on the scale of the Manhattan Project has been proposed by several distinguished climate scientists. These scientists know well the danger of certain tipping points for radical climate change (such as the Greenland icecap melting) that could occur if no effective mitigation is attempted soon and almost certainly will occur if business as usual continues for too long.

The proposal developed by Yale economist William Nordhaus, included in his 2013 book, The Climate Casino, outlines how a price could be placed on carbon dioxide emissions. Although Nordhaus’ strategy calls for immediate action, his suggestions have been criticized by some members of the environmental community as inadequate, while his former editors at the Wall Street Journal think he’s backed away from business interests too much. Nordhaus’ approach incorporates calculations from the best climate models into an integrated assessment model that includes economic projections, population assessments, and future technological developments—the very components a proposal needs in order to receive serious consideration from legislators.

One merit of this approach is the conspicuous role of the discount rate on money invested to mitigate and control the effects of carbon dioxide emissions. The discount rate is a measure of the future value of money. Since there is risk involved in all investment, whether by governments or businesses, business-oriented investors tend to seek fairly quick returns before possible inflation can greatly decrease the value of their investments. And so their preference is typically for a high discount rate. Environmentalists tend to take the longer view, focusing more on future benefits and thus favoring a lower discount rate while accepting more economic risk in case of significant inflation. Since predicting future developments in mitigation technologies is inherently difficult, it’s not always obvious what the discount rate should be. In either case, the rate for money invested on an annual basis can be varied annually by Congress to accommodate changing economic conditions.

Emphasizing the discount rate also allows one to assess what ethical approach toward future generations is in the minds of the lawmakers. A discount rate that exceeds the inflation rate raises suspicion of giving too much to business at the expense of mitigation. Yet a very low one may have damaging effects on the health of the economy, hindering the development of new technologies. The consequences of this latter scenario would also invariably reduce public support for expenses associated with mitigation efforts and therefore could be self-defeating.

No one can doubt the complexity of the issue at hand, and, unsurprisingly, the “devil” once again emerges in the details. We may have little enthusiasm for the current, marginally functional 113th Congress, but we must note the difficulties of the legislator’s task when dealing with climate change. Perhaps with this in mind, Nordhaus recommends a discount rate intermediate between the extremes.

His calculations are sobering. They reveal the almost shocking result that if all major emitters don’t cooperate to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, it will be effectively impossible to achieve the Copenhagen limit of 2°C for the global temperature rise. If the goal is set at 3°C, achieving it will be possible, but extremely (perhaps prohibitively) expensive without global participation. Deeply disturbing are the calculations by climate scientists showing that a major tipping point may be reached at approximately 3.5°C. According to the best current climate science data, rapid and irreversible melting of the Greenland ice cap can then be expected, raising the sea level by twenty-one feet, flooding every major seaport in the world, and creating catastrophic conditions in low-lying nations like Bangladesh. It’s no secret that many U.S. military intellectuals familiar with what causes major wars regard this possibility with great trepidation.

In light of these considerations, it’s not surprising that a politically moderate economist like Nordhaus who trusts the science of climate change would conclude his book with the following assessment:

A fair verdict would be that there is clear and convincing evidence that the climate is warming; that unless strong steps are taken, the earth will experience a warming greater than it has seen for more than half a million years; that the consequences of the changes will be costly for human societies and grave for many unmanaged earth systems; and that the balance of risks indicates that immediate action should be taken to slow and eventually halt emission of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

Western forests continue to burn with increasing intensity while major agricultural states continue to dry out and storm surges on the Eastern seaboard increase in destructiveness. The climate picture isn’t pretty and the political one may be worse, though opinion could change if a major climate disaster were to occur (albeit too late for the victims of the tragedy). Though many of the more vociferous climate contrarians are on the way out, they’re being replaced by an army of basically decent people whose ignorance of science makes them easy to fool. Articulate propagandists would have them march in lockstep to the polls and vote to deny all government regulatory efforts, which are regarded as the enemy of liberty. Without proper science education, these people are unable to deal with issues as complex as climate change. Unfortunately, there’s no way of improving widespread educational deficiencies in this society overnight.

That leaves the burden of proof and action to those fortunate few with a solid grasp of climate science. Sadly, only a minority of the American population today is sufficiently well educated when it comes to science and technology. Eugenie Scott, former executive director of the National Center for Science Education, revealed in her research how poorly the average American student understands science and other technology related subjects. Without stronger efforts by those who understand these issues to better educate both the public and our politicians, there is probably little hope for significant progress on controlling climate change soon enough to prevent disasters greater than those we have seen so far.

Riffing on the old typing drill to illustrate what this still young society must embrace: now is the time for all good people to come to the aid of their planet.