And Justice for Nones

In his first inaugural address, President Barack Obama famously included nonbelievers among those who are dutiful citizens of this nation. But while one in five U.S. citizens responds “none” when asked which religion he or she affiliates with, all nine U.S. Supreme Court justices profess affiliation with one religion or another. If President Obama has another opportunity to appoint a justice to the highest court in the land, he should, in all fairness, appoint the first “none” justice.

The important legal reasons for appointment of a none to the Supreme Court can be summed up by the observation that religious justices have demonstrated an utter lack of understanding of the none perspective. Nones range from the disinterested to the rabid opponents of religion, from spiritualists to naturalists. But their perspectives on religion have common elements that are missing from Court decisions on religious rights and the establishment of religion.

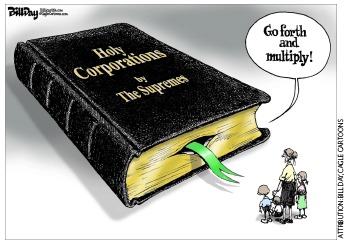

The recently concluded Supreme Court term included the Burwell v. Hobby Lobby case, a classic example of religionists’ increasing demands for favorable treatment from the courts. In a 5-4 vote the Court’s majority granted Hobby Lobby, a private corporation, the right to deny its employees healthcare coverage for four types of contraception that it objects to on religious grounds.

The most important problem with this ruling (and one that a none justice might have emphasized) is that it ignores the negative implications of requiring the government (and therefore taxpayers) to pay for employees’ contraception when corporate employers won’t foot the bill on religious grounds. The ruling fails to require these employers to pay extra for the high costs incurred by like-minded religionists due to additional pregnancies and births. It tears at the fabric of our nation by short-circuiting the long-honored understanding that everyone contributes for their part, whether or not they like the part other people get. Finally, the Hobby Lobby decision violates the Establishment Clause (including the express language of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom on which the clause is based), in that it requires someone to pay for someone else’s religion.

The most important problem with this ruling (and one that a none justice might have emphasized) is that it ignores the negative implications of requiring the government (and therefore taxpayers) to pay for employees’ contraception when corporate employers won’t foot the bill on religious grounds. The ruling fails to require these employers to pay extra for the high costs incurred by like-minded religionists due to additional pregnancies and births. It tears at the fabric of our nation by short-circuiting the long-honored understanding that everyone contributes for their part, whether or not they like the part other people get. Finally, the Hobby Lobby decision violates the Establishment Clause (including the express language of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom on which the clause is based), in that it requires someone to pay for someone else’s religion.

A “none” justice would be able to drive home the broader point that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, on which the Hobby Lobby decision rested, is an unconstitutional attempt to interpret the Constitution so that it grants privileges that the Establishment Clause prohibits. A none justice could remind the Court that its interpretations of the Constitution should not be entirely based on a mere statute.

Most nones also disagree with the Supreme Court justices on legal issues pertaining to the use of religious symbols for secular purposes. For example, the Court held in Lemon v. Kurtzman that a monumental, unadorned cross of the type revered by and widely associated with many Christian sects could remain on public property because it was placed there for a “secular purpose.”

The Supreme Court’s majority errs regarding the application of this standard. The cross is deeply rooted in the doctrines of all Christian sects and is widely displayed on private property as their main symbol. From an outside perspective, the non-incidental use of a symbol central to a religion cannot fail to convey a sectarian message. Having a none on the Court could force the majority to address the fact that they claim to speak for those with no religious affiliation without knowing what they’re talking about. Jurisprudentially, a none justice might argue more successfully than the dissenting justices in Lemon that the level of scrutiny for a supposedly “secular purpose” must depend upon the extent to which a symbol is associated with the religion that uses it.

Accordingly, symbols associated solely with dead religions, such as representations of Egyptian, Greek, and Roman deities, could still be publicly used as historical artifacts reflecting the evolution of human thought. Likewise, in the rare instance that a public monument built for a predominantly secular purpose cannot avoid the use of a religious symbol, the monument could still pass muster if the religious symbol is an incidental part of the monument’s overall symbolic value.

A none justice is also needed so that the Supreme Court’s decisions better reflect the concerns of nonreligious Americans regarding the posting or recitation of religious creeds. Nones generally don’t want advertising for religious sects in public spaces, especially when those advertisements are paid for with public money.

Take the Court’s majority ruling on invocations at town meetings in Town of Greece v. Galloway, which states that a governmental body may allow invocations on a nondiscriminatory basis. That decision acknowledges that the town of Greece, New York, used an “informal” selection process. This glosses over the fact that the persons giving invocations were hand-picked by one or more public officials. By selecting the invitees, the officials were determining the general nature and sectarian content of the invocation. A none justice could insist upon a more equitable policy, wherein officials are prevented from selecting the speakers to deliver invocations.

Despite the majority opinion’s claim in Town of Greece that the government cannot restrict content, the opinion addressed questions of content when it stated that speakers may be required to refrain from proselytizing or disparaging others. A none justice could steer the discussion toward a better standard of content that limits invocations to statements of values. After all, religionists and nones may argue around the edges, but we hold almost all fundamental values in common, and well-expressed common values can be as effective as religion when imploring our elected officials to use their power to advance society.

Indeed, a none justice could make the larger distinction for the other justices that reducing the presence of religion in the public sphere is limited to the absence of religious brands. Without proscribing the invocation of high principles or even the gods generically, a religion-neutral public sphere would be free of references to Jesus and the Trinity, Jehovah, Moses, and Allah, every bit as much as it is free of Chevrolet, Google, and Apple.

Under this formulation, religious statements could still be incorporated into public monuments when relevant to the person honored. Thus, religious statements by a religious and social leader like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. are appropriate in a public monument to him.

Throughout history, religionists have attacked and vilified nonbelievers. Today there are still religious leaders who spread lies to generate prejudice against those who don’t believe in a deity or who aren’t affiliated with any particular religion. The appointment of an open none to the U.S. Supreme Court would help heal the effects of that prejudice. The religious justices who have dissented in the cases mentioned here are proof that intolerance is easing, but their opinions have adequately reflected only the perspectives of non-Christian religionists facing Christianity in the public sphere. Equally important, having a none justice would show citizens of our nation and the world that someone who doesn’t proclaim a religious belief will push to keep society free and open for all.