Robert Louis Stevenson Says No to Religion

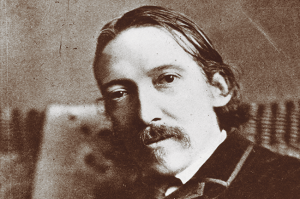

Photo by Popperfoto (Getty)

Photo by Popperfoto (Getty) ON THE NIGHT of January 30, 1873, in his home at 17 Heriot Row in Edinburgh, Scotland, Robert Louis Stevenson told his parents that he no longer believed in God. He’d grown tired of pretending to be something he was not (“am I to live my whole life as one falsehood?”). His father, a strict Calvinist who always managed to justify his beliefs, was, for once, at a complete loss. His reply to Stevenson was a mental bomb of shame: “You have rendered my whole life a failure.” His kind, yet distant mother’s reply took away whatever stability had remained in the home: “This is the heaviest affliction that has ever befallen me.”

Stevenson went to his room and wrote his friend Charles Baxter. In the letter, Stevenson could only process the moment through a thick black sarcasm: “O Lord, what a pleasant thing it is to have just damned the happiness of (probably) the only two people who care a damn about you in the world.” Two paragraphs later, that sarcasm fell into darkness: “What is my life to be, at this rate…what the devil am I to do?”

It was a question Stevenson had struggled with for years as he attempted to live up to his father’s expectations. He spent his first years at the University of Edinburgh as a “lean, ugly, idle, unpopular” and unmotivated student. His father wanted him to go into engineering, but the spell of ink had entranced Stevenson enough that he told his father that he could not continue down that path. At the age of twenty, Stevenson changed tracks and attempted to be a lawyer—wishing to at least slightly please his father by settling into a somewhat stable profession.

His time studying law is quickly explained in a comment by a fellow law student: “We did not look for Stevenson at law lectures, except when the weather was bad.” At the age of twenty-two, one particular highlight for Stevenson was being a member of the Speculative Society, where he would debate life’s meanings with friends, often standing and pacing, his wiry frame never at rest. From out of this club came the inspiration to start another “edgier” group, called L.J.R., which stood for Liberty, Justice and Reverence. Stevenson and his cousin Bob started the group in the hopes of, in a manner of speaking, sticking it to the man. Their first rule was simple: disregard everything taught to you by your parents. When Stevenson’s father discovered the L.J.R. manifesto, he demanded that his son fess up about his beliefs, which he did on that January night, and his home broke asunder.

For the next few months, Stevenson lived in a perpetual state of tension, or, as he put it: “It is always a picnic on a volcano.” The constant tension meant daily glances of disappointment and the nagging fear that he had lost the unconditional love of his parents. His health deteriorated, and he fell into depression, often lying in his bed for days. In July, six months after the event, Stevenson wrote a melancholic, borderline fatalistic letter to Elizabeth Crosby. In the letter, he describes his days:

I rise at half past six in the morning and walk into town alone before nine…I go to classes, or oftener stay away from them and sit smoking in the Public Princes Street Gardens, where one sees a great deal of easy life in shirt-sleeves, shop girls and shopmen…vague wandering old men…[I] eat a very good dinner, smoke very placidly in the garden, read or write, and go early to bed. A life of beautiful regularity, is it not?

It was, but it wasn’t. In an attempt to fight against his dour mood and illness, Stevenson traveled to Suffolk to visit a cousin. At that point in time, Stevenson would have traveled to a manure farm, if they existed, his body and mind a pulped shipwreck. He needed friends, he needed heroes, he needed parents, and he needed support. He found the latter in a thirty-four-year-old woman named Frances Sitwell—his first love, one could say. Sitwell introduced Stevenson to an art critic at the time named Sidney Colvin.

After the first meeting, Colvin was in awe, describing Stevenson as a “youngster, already to have lived and seen and felt…more than others do in a lifetime.”

Though Colvin would eventually assist Stevenson with publishing connections, it was Sitwell who pulled Stevenson through those storm-ridden months of family angst. Although he poured his heart out to her letter after letter, Sitwell, who had willed a separation from her philandering husband, remained just distant enough not to get attached. Still, like a man standing on the edge of a mountain, arms out, pleading, for months Stevenson wrote her passages like this:

Your sympathy is the wind in my sails. You must live to help me and I must do honor to your help…[people] will wish that they could have lived where they could have known you, and the others will set you before them as a model.

Sitwell loved the attention, but she could not reciprocate. In a symbolic way, she was the only member in the audience of a play titled Stevenson. The final lines of that imaginary play would have no doubt been what Stevenson wrote to her later, stuck inside the pit of unrequited love:

I wish to God I did not love you so much; but it’s as well for my best interest as I know well enough. And it ought to be nice for you; for you need not fear any bother from this child except petulant moments. I am good now: I am, am I not?

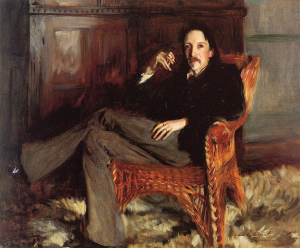

John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson was completed in 1887. It’s currently on display at the Taft Museum of Art, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Whether it was the mental attrition his father put him through, the unrequited love he experienced for Sitwell, or the aimlessness of his career path, near the end of his twenty-second year, Stevenson trudged into the doctor’s office at 5’10” and around 118 pounds—a human beanpole. The doctor’s diagnosis was simple and true: Stevenson was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. The doctor recommended, like many did during this day and age, a long trip alone. Stevenson traveled to Mentone, on the south coast of France, and arrived there a day before his twenty-third birthday.

While at a hotel filled with other distressed outcasts, he smoked opium and led “the life of a vegetable…I eat, I sleep, I sit in the sun.” Though that sounds as if the vacation was without thrill, the absolute freedom he enjoyed, separate from all, was a delight he expressed to Sitwell: “I nearly danced again.” And then, writing on his birthday, “I have here the nicest room in Mentone.”

Sitwell failed to send a letter on his birthday, while Stevenson was going through a process that would help him disconnect from the drudgeries of his dependent lifestyle. Over time and distance, he would place her in the healthier role of a friend, and would begin to think of his life more as an individual, rather than a young man hoping to please his parents. Stevenson was never deeply concerned about religion—surviving was more his problem. By telling his parents he no longer believed in what they believed, he was merely trying to establish his own identity, and, as many of us know, that action will always be initially painful.

Personally, I find Stevenson’s twenty-second year to be the most admirable in a letter he wrote to Frances Sitwell on September 15, 1873. He’d been battling his domestic war for months, had been denied many times physically by her, and he had just been weighed by a doctor and shown how the claws of stress had scratched him to the edge of his life. Through it all, Stevenson found the courage to write these lines: “Does it not seem surprising that I can keep the lamp alight, through all this gusty weather, in so frail a lantern? And yet it burns cheerily.”

Stevenson would go on to become a literary star admired by the likes of Jorge Luis Borges, Marcel Proust, Arthur Conan Doyle, Henry James, Ernest Hemingway, and Vladimir Nabokov. Stevenson wrote a total of twelve novels, including Treasure Island (1881) and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), numerous short story collections, four books of poetry, and a variety of travel essays. It was a career many parents would have accepted.