The Bad Book

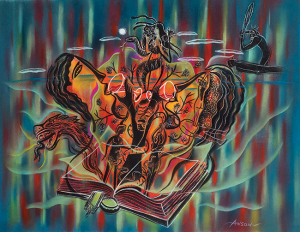

Illustration by Anson Liaw

Illustration by Anson Liaw How much better would the Bible be if the poet voice had won out

over the priestly?

In the summer of 1957, fresh out of the navy (remember the draft and the Korean War?), I rented a cabin for a month on an island in Canada just north of the Minnesota border and set out to become a writer. Like everyone else, I’d been a writer all my life, but now I was going to lay out some principles and get serious about it. I took with me all of Samuel Beckett’s texts then available, some of the absurdist playwrights, a few philosophers and theologians, some dirty Olympia Press books I’d picked up in Paris, and the Bible. I decided to read the Bible straight through, front to back, to see what sort of a story it was. My grandfather had been a Bible Belt Methodist preacher, my father a Sunday school superintendent and choir soloist, and, in that postwar midwestern Hollywood era, church was a deeply ingrained family and community habit, so I was still shaking the Good Book off. I found the porn holier, Beckett wiser, and wrote a kind of Kierkegaardian response (I liked the Dane’s style at the time) to the book and the dangerous institutions it spawned. I supposed that was it. Through Beckett I’d found my vocation, and I was leaving most outworn conventions behind, religion and other traditional fictions included.

But there had been a terrible Christmastime explosion in one of the coal mines near where my family lived, and, as a college kid home for the holidays, I had helped report on it for my father’s newspaper. That had led to some early stories, and one of them was eventually accepted by Saul Bellow and Keith Botsford for their celebrated literary magazine, The Noble Savage. Writer friends and editors, rejecting my “breakaway” fictions, urged me to attempt a book something more like the Noble Savage mine disaster story, and eventually I did, mainly to prove that I could. Thus, The Origin of the Brunists. So it could be said that the Bible helped launch my writing life, though it was less the book than the communal madness it tended to provoke that had my main attention.

Origin was about the formation of an apocalyptic cult around the bedside of a lone mine disaster survivor, and, at the time, I imagined a sequel for it, set in a time when the cult, after failed prophecies, had become an established evangelical religion. But I was no longer writing that sort of fiction, so although I took extensive notes through the decades that followed, a return to it seemed unlikely—until the election of young George W. Bush to the U.S. presidency and the rise to power of that swarm of crazed evangelicals along with him. Fortunately, most of the western world has set the Bible and its savage worldview aside, but not my compatriots, who, ignoring the enlightened skepticism of the Founding Fathers, are far more likely to believe in the devil or the virgin birth of Jesus than in evolution or global warming. So, when W. declared a “crusade” against the infidels, calling up his knights in heavy armor and sending them rumbling off to Baghdad to unleash their holy shock and awe, I felt it was time for The Brunist Day of Wrath. Most of my eighth decade (so valuable! so gone!) was devoted to it. I thought of it as a comic work, though like the human comedy it is not always funny.

The new project forced another cover-to-cover reread of the Bible, but I had not entirely left it behind. In 1967, not long after Origin first appeared, I taught a reading-writing workshop at the University of Iowa called Exemplary Ancient Fictions, a course I continued to teach, off and on, over the next forty-five years, and Genesis, a kind of theologically modified folktale compilation, was usually one of the texts. Except for the Enuma Elish and maybe Hesiod’s Theogony, Genesis was the least appealing of the books on the syllabus, but its tales and characters have fairytale status in the western world, even where not part of the catechism, and it is a good place to intrude upon a text and attempt variations.

In class, we focused on the so-called J or “Jahwist” voice (believed by some to have been that of a unique woman poet, using traditional folktale materials), but compared her (or his/their) tales exemplarily to the contributions of the P or “Priestly” voice, which were mostly negative and orthodoxly censorious: the writers versus the priestly nonwriters—those whom Sally Elliott, The Brunist Day of Wrath’s resident debunker, calls “a bunch of beardy guys with tight assholes.” Had it not been for P, we might have had (and in class did have) stories about the stinking splendor of Leviathan, the monstrous Riz and Behemot, and the amazing Adne Sadeh, also known as Adam, the strange animal called man, a human creature fastened to the ground by his navel-string, severing it being the only way to kill him so he could be served up as an edible delicacy. We might have heard more about the rebellion of the “dark waters,” about Adam’s first wife, Lilith, and the curious manufacture of Eve, about Cain’s nightmarish life after his exile, and about the annoyed First Man’s killing of Samael’s squalling son, whom he and Eve are babysitting. The damned kid keeps screaming even after he’s dead, so Adam chops him up and cooks the bits and he and Eve eat them, no doubt washing them down with good wine (legend makes it clear that the fruit the serpent tempted them with was not an apple but fermented grapes). But when they lie to Samael about this, the kid pipes up from inside them and gives them away. Samael in his paternal rage is ready to kill them both, but God loves Adam and gives him the Torah as a kind of knowledge-shield. Which, in turn, makes the angels jealous and they also want to kill Adam, but the Torah is like krypton and foils their plot, so they steal it and throw it into the sea to set up future adventures. None of this adds to God’s or Adam’s grandeur, but at least it doesn’t try to make men feel guilty for their own deaths, as the priestly version criminally does. Had these stories and the many like them got past the censors into God’s handiwork, one can well imagine the scramblings of the literalists to justify them.

After Genesis, the Good Book generally falls away into a humorless So-So Book at best, a Bad Book mostly, getting worse as it goes along, sinking into the New Testament’s celebration of a deluded monomaniac, who brings the good news that the world is ending even as he speaks, thereby forming a cult around himself that shapes the world we live in now. It’s no miracle. As Jesus himself says in The Brunist Day of Wrath (if it is he, and not a lunatic with a Christ parapathy), “Along come mad Paul, the unscrupulous evangelist scribblers, the Patmos wild man, the remote muddle-headed church fathers, so called, plus a few ruthless tyrants and you’ve got a powerhouse world religion.” All the world’s heavies, needing to hang on to what they’ve got while pushing their enemies’ noses in it, find books like this one the perfect tool for suckering a mob.

There are a few universally acknowledged and overpraised poetic high spots in the Bible like the Song of Songs (sex—yay!), the kvetchings of Job (a conservative tale about a stubborn rich man, with a Hollywood ending), the songs and sayings anthologies (dime a dozen), and Ecclesiastes, with its ancient carpe diem message (it is, in effect, an elaboration of the alewife’s message to the wayfaring Gilgamesh a millennium and a half earlier), but as my penciled-in marginalia from Origin of the Brunists days repeatedly bewail, it is for the most part unbearable diatribe exhibiting an appalling and infantile view of the universe, and bottoming out with Revelation, a displaced Old Testament nightmare so over the top it’s almost comical, like a laughable backyard horror movie.

The Brunist books, however, are less about the Bible than about its fanatical adherents and the toxic institutions and culture they give rise to. The book can be dismissed as mere literature of disputed quality, but not its believers, who can be dangerous, not only to all nonbelievers but to the planet as well (hooray for death! bring on the apocalypse!). The human species does not need texts like this one to kill and torture others, they’d do it anyway, and with pleasure, but the texts serve conveniently as pretext. To paraphrase the old NRA slogan: the Bible doesn’t kill, people do. But just as guns make it a lot easier to kill and offer up new temptations and opportunities to do so, so does the Bible make it a lot easier to justify the slaughter of nonbelievers and offer up a rationale for recklessly exploiting a world that has no future. As Sally says in Wrath: The world is being ruined by people with childish ideas and grownup weapons. COPYRIGHT © 2015 ROBERT COOVER