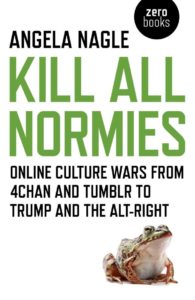

Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4Chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right

BOOK BY ANGELA NAGLE

ZERO BOOKS, JUNE 2017

136PP.; $16.95

Before he was the White House chief strategist, before he was a founding member of Breitbart News, Steve Bannon served on the board of a company called Internet Gaming Entertainment. IGE made its profits by hiring poor Chinese workers to play World of Warcraft all day, then selling the digital goods these workers acquired to affluent Western customers. This was evidently a sustainable business model until the company was sued by WoW players for the neurotic in-game distortions it was causing. IGE was ruined by the lawsuit—it eventually had to change its name and begin exploring other profitable outlets in gaming. The legal experience, however, wasn’t bad for Bannon. Besides being appointed CEO of the rechristened Affinity Media, he also believed he had found an online vanguard for his deranged political ambitions: what’s now called the “alt-right.”

Angela Nagle’s short, intelligent book, Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4Chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right, is the story of how these “teenage gamers, pseudonymous swastika-posting anime lovers, ironic South Park conservatives, anti-feminist pranksters, nerdish harassers, and meme-making trolls” had until recently been gaining so much cultural, political, and ideological momentum. Somehow the politics of David Duke combined with the middle-class whininess-cum-sadism of Generation Xers became fashionable online. Explanations are needed. Nagle brilliantly provides them.

Modern conservatism has always tried using sneers and sarcasm to attract younger members. In the 1980s card-carriers of Britain’s Federation of Conservative Students wore “Hang Nelson Mandela” stickers (ironically, of course). In his Letters to a Young Conservative, Dinesh D’Souza—a former editor of Dartmouth Review, a conservative student newspaper infamous for its witless skylarking—gave propaganda advice to campus reactionaries, suggesting for comedic effect they “distribute a pamphlet titled ‘Feminist Thought’ that is made up of blank pages. Establish a Society for Creative Homophobia… Put a picture of death-row inmate Mumia Abu-Jamal on your Web site and instruct people who think he deserves capital punishment to click a button and execute him online.”

Then there are right-wing liberatirans like FOX’s Greg Gutfeld who practice the fatiguing nineties shtick of total ironic detachment. Gutfeld has written books on how conservatives are really the funny ones and the Left are all just politically correct killjoys. On YouTube one can find countless videos of impertinent conservative speakers “DESTROYING” or “ANNIHILATING” college sophomores who heard about politics for the first time six weeks ago.

Lately, however, this “dark humor” has become even more ill-tempered, captious, and—to put it lightly—ungallant. On Twitter, right-wing “trolls” put the names of Jewish journalists in triple parentheses—lest anyone be caught off-guard by Jonah Goldberg being Jewish—and send images of concentration camps to their accounts. Women are threatened with rape and given pornographic details of their impending murder. Muslims are harangued with quotes about Muhammad being a pedophile and of statistics showing the popular support of Sharia among European Muslims. (The average Muslim likely knows the obligations of Sharia about as well as the average Christian knows the obligations of the Beatitudes.) Nagle raises important questions about this softcore sadism masquerading as intrepid flippancy, “Do those involved in such memes any longer know what motivated them and if they themselves are being ironic or not? Is it possible that they are both ironic parodists and earnest actors…at the same time?”

But if a consciously low-blow sense of humor has always been a rhetorical ploy of right-wing proponents, then why was it a failure for recruitment until just recently? Nagle finds plenty of reasons—and plenty of blame to go around as well.

First, it’s obvious to almost everyone that the current electoral coalitions of both major political parties are spurious and cynical. As Nagle gently puts it, the Democrat’s alliance of “class politics and social liberalism have not always sat comfortably together” and neither has the Republican’s ideological mixture of “social conservatism with free-market economics.” When authentic forces for solidarity are ignored, wide wedges for those interested in subverting democracy and toleration will appear.

Second, the structure of social media—horizontal, attention-dependent, impersonal—encourages the more thuggish and vulgar instincts and enthusiasms of people. Third, “Tumblr liberals” (as Nagle calls them) cried wolf for so long over trivial cultural matters that they eventually attracted “the real wolf…in the form of the openly white nationalist alt-right who hid among an online army of ironic in-jokey trolls.” Fourth, since the sixties, “the culture of non-conformism, self-expression, transgression, and irreverence for its own sake” has been associated with a sort of affectless left-wing bohemianism, but in fact it’s a morally and politically neutral ethos. Alt-righters have employed it to dupe young people into thinking they’re being rebellious by railing against “postmodernism” (is there a safer thing to rail against in America?) and by keeping lists of Jewish reporters.

© Denisismagilov | Dreamstime.com

Fifth, because of the sexual revolution, a “sexual hierarchy” has emerged whereby a “large male population at the bottom of the pecking order” isn’t having as much intercourse as their youthful entertainment from Hollywood and San Fernando Valley promised them. Women nowadays are free to choose the men they sleep with, and surprisingly they’re not choosing the guy “negging” them about their haircut, clumsily trying to “initiate contact,” and talking about the “research” he’s done on the gender wage gap. Finally, the old opinion-making media has been replaced by “constantly online, instant content producers.” Gatekeepers on Twitter, YouTube, and elsewhere more and more determine what news items are discussed and in what manner. For reason’s unknown, anytime a new type of communication medium is invented, obscure demagogues are the first to benefit.

Nagle’s explanations are all very convincing. The only problem with them is how little they explain. Part of this stems from the brevity of her analysis. The book is really more an extended essay and thus lacks the necessary historical depth for its conclusions to be definitive. It would’ve been interesting for Nagle to add an historical dimension, so she could’ve revealed that most the male grievances inflaming the alt-right today have been around since time eternal.

What are we to do about the alt-right? Only a couple months ago the question was a much more urgent one to answer. Since President Trump took office, however, there seems to be a general fragmentation taking place between true believers of a fascist utopia and mere wannabe nihilists. Nagle’s received some heat for blaming Tumblr liberalism for the rise of the alt-right. Nonetheless she’s correct in doing so. Just because alt-righters happen to agree with her on this point doesn’t make it de facto wrong or dubious.

The skinny on our current situation—that Nagle is too polite and scholarly to say—is that there are a lot of men nowadays who are servile and credulous but who desperately desire to be perceived as independent and enlightened. They want to be sexually successful but don’t want to bother with being interesting or charming or physically attractive. They want to take the ready-made answers they hear on YouTube, then regurgitate them on Facebook, and complain about how everyone else is herd-minded. They want to ridicule the cult of feeling while remaining sentimental about the forces of hierarchy and tradition. They want to convince themselves and others that it’s “edgy/countercultural/transgressive” to be loudmouths for the leisure class.

Nagle approaches the alt-right with understanding and patience. Her political taxonomies are careful, her sociological explanations are persuasive, and her psychological evaluations are considerate. She has a genuine sympathy for her subjects and a genuine solidarity with their victims. Most important, she shows that psychological and economic analysis are complimentary rather than at odds. Read Kill All Normies, then everything else Nagle has written. It’ll be time better spent than listening to your favorite podcaster complain about “political correctness” for the nth time.