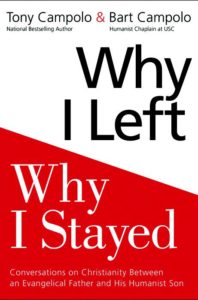

Why I Left, Why I Stayed: Conversations on Christianity Between an Evangelical Father and His Humanist Son

BOOK BY TONY CAMPOLO AND BART CAMPOLO

HARPERONE, 2017

176PP.; $15.00; $10.99 (KINDLE)

Most books about atheism, or about Christianity, are written by one person, with one viewpoint, for one audience. But in Why I Left, Why I Stayed, Bart Campolo, humanist chaplain at the University of Southern California, and his father Tony Campolo, a best-selling Christian evangelical author and pastor, present two very different perspectives in an attempt to honestly discuss the religious differences that now divide them.

This short book consists of alternating chapters written by father and son, telling and reacting to the path Bart took from believer to nonbeliever, and the resulting changes in his life and belief system. Both authors write well, with engaging and concise styles. The first half recounts Bart’s falling away and its effect on both him and his family, while the second half is more issue-oriented, covering topics such as Jesus, the basis for morality, and dealing with death. The love and respect each has for the other shines through both accounts and provides a good example of how both sides in this debate might better approach each other.

For Bart, who earlier in his career followed his father into the Christian ministry, the road to atheism was a slow, intellectual one, devoid of anger and resentment but filled with sorrow and a feeling of loss. I think it’s true for a fair number of atheists (myself included) that the loss of faith wasn’t something we sought, but something which found us, despite a happy upbringing in a religious household. In many ways this path makes a stronger argument for atheism, since the easier, happier path would have been to stay a Christian.

But it’s not an argument that persuades Tony, Bart’s father. Tony’s faith is not of the fundamentalist, the-world-is-6,000-years-old variety, but is based on a strong and vibrant belief in God’s place in the world. His evangelism is strong on helping fellow humans and bringing Christian values of charity and love to this world. So there are no easy arguments to be made against Tony’s role for religion based on hypocrisy or meanness.

But for those with a godless perspective, in the mirror of Bart’s road to atheism, Tony’s continued clinging to faith strikes one as a little sad. Too often, Tony argues by story rather than by reason. He’ll tell a dramatic tale, leading up to a climax where the subject of the story suddenly has an insight that he or she feels is indeed proof of the presence of God. Tony then regales the reader with what comes off to nonbelievers as a smug conclusion unjustified by the story itself and not even suggesting a supreme being.

For all the love he has for his son, it soon becomes clear that Tony really just doesn’t understand his son’s nonbelief. That starts to come through a little more in the second half of the book, as his attempts to understand give way to him simply stating his son’s thinking is wrong. For instance, Bart writes a moving chapter titled “Facing Death the Secular Humanist Way,” in which he explains how it’s the very idea that we won’t exist forever that makes our lives so precious and infuses them with meaning. Tony’s chapter on this is titled dismissively “Why Secularists Can’t Face Death.”

And yet, the strength of this book lies in presenting both sides of the story and thereby providing a solid foundation for discussion between believers and nonbelievers. The love and respect the authors have for each other, as father and son, helps steer it away from the antagonistic stereotyping that might otherwise be attached to any book that provides only one side or the other. It’s a book that people with opposing views can and ideally should read and discuss together. And that’s where its real value lies.