Poetry & Paint

“Painting is poetry that is

seen rather than felt, and

poetry is painting that is

felt rather than seen.”

—Leonardo da Vinci

One of my dearest friends in my life was a painter named August Mosca. Were he alive today, Gus would be 112 years old. When we met he was a sprightly eighty-two and I was just a breath or two beyond thirty. Historically, there has always been a great affinity between painters and poets—Frank O’Hara’s friendship with both Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning come to mind—and Gus and I became fast friends.

I admired that Gus had spent a lifetime at his art and somehow had managed to squeeze out a living being a man who spent as many hours in the day that he could painting and drawing. We spent many happy times together in the little studio shed behind his farmhouse on Long Island talking for hours about the nature of art and creativity, and it nourished each of us at a time when we both needed it.

One day we stood at his window, looking out at the yard behind his house, and he noted the beautiful purples in the trunks and branches of the tree behind his house. He wondered if I could see the colors and I told him I couldn’t. To me they looked like trees. Then he set a canvas upon his rickety old easel and began to paint. A day or two later he shared the painting with me. Sure enough, there was purple in the trunks and branches of those trees. After that I never looked at a tree in the same way. Gus hadn’t created a new reality but he’d infused the reality he saw with the hues of his own perception, and through his art, I was enriched and enlightened about the physical world and the nature of light in ways that could not have simply been explained with words.

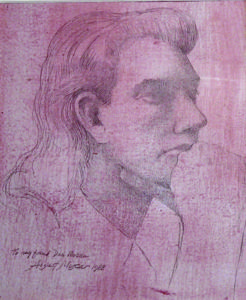

One of the three portraits Mosca drew of Moran during the artist’s lifetime. (Image courtesy of Daniel Thomas Moran)

Gus did three portraits of me in the years of our friendship, and when I look at each of them it’s somewhat bewildering. In many ways they don’t look like me. More critically, they don’t look like the “me” I see when I look into a mirror. They do, I am very certain, look like the “me” that August Mosca saw. They look like the person he knew and cared about. Incredibly, when I look at those portraits all these years later, I can feel myself there. What I see is not the figure of a man I once was but rather the essence of myself. It was something about me that Gus could recognize and evoke with paint.

This is what art does for us: it presents a reality that we might never get to see in any other way. Through the vision, the perception, and insight of the artist, the world blossoms before us, it reverberates with light and shadow and sound. It offers us a means of recognition. One need only look to the works of the great Impressionists to see that the world is more than what we think it is. It moves and shimmers and assumes a new and remarkable presence. It expresses itself in ways that only some are able to perceive and translate for others. And so it is with poetry and with poets.

I have written poems for more than forty years. The thing that drives every one of them is my desire for understanding, my passion for acuity, and my determination to see more than is there—to note and to elevate the overlooked. In that, I hope to create insights into the nature of things and find connections between things that seem to hide just beneath the veils of our vision and understanding. What I hope will emerge from the struggles of paying close attention and endless hours of reflection is to find the purple in the trunks and the branches of trees, and beyond that a comprehension of why that matters. When I succeed (often I don’t), that insight can be shared with others who might be willing to read what I write. There is a magic to it that I have yet to fathom; I don’t know where these poems come from or when they will arrive, or how they find me. But I live my life trying to be ready to receive them when they do. (Other poets may write in a more deliberate or planned way, and that is just as valid.)

Poet Daniel Thomas Moran (right) and painter August Mosca (Image courtesy of Daniel Thomas Moran)

The best way I can explain it is to say that, for this poet, writing poetry is like a waking dream. We all know that feeling of waking in our bed and recalling a dream we just had. At the outset, it sometimes doesn’t make sense. There are places and people and events and we’re left to wonder why they all gathered that night in the rooms of our dreaming. And yet, even if we are wont to explain it all in literal terms the way we might add a column of numbers, knowing that they must always arrive at a defined result, there is something transcendent about dreams, something comforting. In them is a truth beyond our waking reality. Poets are dreamers, surrounded by metaphors and symbolism. The world presents puzzles to us every day. Poets like to play with those puzzles, and they infuse themselves into them in ways that aren’t obvious, especially if the poem has any merit. My wife will often look at me and say, “Where are you?” and I reply that she knows where I am, she has lived with me a long time. I am in that place where poems might be found. It’s where I live many hours of the day, in the playground of my imagination.

Imagine how bleak the world would be without poetry. There would be no Shakespeare, no Whitman, no songs, and no holy books. It’s all poetry. Like all art, poetry asks us to be willing to take a journey, to explore, and to be patient. Not all art affects all people the same way. I’ve wandered museums and seen many things that did not move me at all. But when I find that one thing that does, it is profound and delightful. It calls out to me, and I want to climb into it and look around. It makes me wonder and marvel. It makes me sigh with recognition, and it makes my life just a little bit richer. I have written many books of poems and read many as well. If, in a collection, I find one poem that lights me up, even one line in one poem that lights me up, it has been a worthy effort. When I give someone a book of mine, I tell them my only hope is that they find something in it that means something to them. I hope that in my poems, they might be able to see the purple in the trunks and branches of trees. I hope that in them they find something luminous and moving. I hope that in them, they find themselves.