Exorcising the Ghosts of the Sixties Radical Protests, the New Left, and the “Politics of Eternity”

Large crowd at a National Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam direct action demonstration, Washington, DC, October 1967. (Source: Library of Congress)

Large crowd at a National Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam direct action demonstration, Washington, DC, October 1967. (Source: Library of Congress) “I COULD NOT UNDERSTAND how anybody could rebel against a system so clearly benign.” That authorial “I” was John Updike in his self-deluding memoir, Self-Consciousness; the rebels he was referring to were fed-up blacks, middle-class students, the working poor, disenchanted professionals, and left-wing zealots; and the “benign” system was our own in the 1960s.

That “benign” system was destroying almost two million acres of land in South Vietnam by dropping more bombs on the country than we had dropped in all of World War II and the Korean War combined. That “benign” system had local law enforcement collaborating with the Ku Klux Klan to murder “uppity negroes”—then all-white juries, heartened by defense attorneys to defend Anglo-Saxonism against its enemies, would acquit the murderers. After NAACP activist Medgar Evers was murdered in broad daylight, a representative of that “benign” system, Mississippi Congressman William Colmer, said Evers’s murder was “the inevitable result by politicians, do-gooders, and those who sail under the false flag of liberalism.” It was later discovered that the FBI had known the identity of Evers’s murderer the whole time but did nothing to bring about his prosecution. The bureau was perhaps too busy in its counter-intelligence operations, which included ransacking labor and peace organizations, keeping reams of files on thousands of Americans, trying to convince Martin Luther King Jr. to kill himself, and coordinating with the Chicago police to assassinate Black Panther Fred Hampton. Just some of the “benign” operations of a “benign” system.

America still hasn’t recovered from the sixties. Not psychologically, socially, politically, or ideologically. This is easily proven not only by how often the sixties still get brought up (“At first sign of ‘trouble,’” Tariq Ali wrote in his memoir of the decade, “the lazy journalist reaches for his sixties file”) but by how little we’ve recovered or progressed since then. For all sides—left, right, or center—the arguments, justifications, and tactics are the same today as they were when we had troops in Vietnam (Iraq), fought the Cold War (War on Terrorism), and debated the “permissive society” (“culture wars”).

In his book Road to Unfreedom, Timothy Snyder conceptualizes the “politics of eternity,” where politics is always moving fast yet going nowhere. Has that been our state of politics for the last half century? Are we in some way still stuck in the sixties?

The year 1968 (a year that politically outreaches its calendar days) is turning fifty this year. For both radicalism and the reactionary backlash against it, 1968 is generally considered the pivotal year of the sixties. And looking at all that happened, it’s easy to understand why.

1968

April: Columbia University students occupy campus buildings in protest of the university’s ties with the military, its plundering of surrounding apartment complexes, and the construction of a university gym on the grounds of what was once a neighborhood park. (Locals would be permitted access to a few parts of the gym, but would have to use a separate entrance than those affiliated with the university.) That same month Martin Luther King Jr. is assassinated while in Memphis, Tennessee, supporting organized garbage collectors.

May: Paris is crippled by student revolts and a general strike that involves some ten million French workers (a fifth of the country’s population). The situation so alarms France’s ruling elite that Prime Minister Charles de Gaulle flees to Germany to recruit non-conscripted French soldiers to invade their own country if things get any worse. At the end of May, Britain’s French ambassador writes to his superior, “The French government now looks in a state of disintegration.”

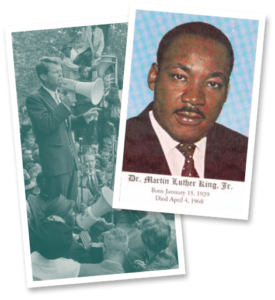

Left: Bobby Kennedy speaks to a demonstration outside the Justice Department in Washington, DC, on June 14, 1963. Right: Picture card showing portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. (Images: Library of Congress)

July: Robert Kennedy is gunned down the same night he wins the Democrats’ California primary.

August: protests at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago turn into a riot. Police and National Guard use tear gas and batons to pummel protesters who are chanting slogans in support of the Viet Cong.

What Columbia, Paris, and Chicago all had in common (besides an anti-imperialist attitude) was the brutality of the police. At Columbia, they tore up the campus then occupied it for days; in Paris, the protesters and strikers garnered the general support of the country’s population because the Parisian police were so indiscriminate in whose heads they bashed; and in Chicago, as one female protester described the night of chaos and carnage, “It was like the Bastille stormed us.”

Put bluntly, in 1968 all hell seemed to be breaking loose. To paraphrase the ever-concise political commentator Murray Kempton, liberals weren’t listening to Democrats, workers weren’t listening to union officials, and black Americans had seen the inevitable fate of nonviolent resistance. Meanwhile the Right was fantasizing about authoritarianism as political responsibility. National Review’s Frank Meyer wrote,

Either the forces of revolution and nihilism will bring the republic down in a welter of disorder or…the people will rise in their wrath and bring into power those who can restore order, at whatever cost to constitutionality and freedom.

Before King’s assassination, the flagship magazine of “intellectual conservatism” was effusive about the “non-violent avenger” and “his legions [being] most efficiently, indeed most zestfully repressed.” William F. Buckley called for a “sign of firmness” by the state and “repression of the lawbreakers” (although he liked to intermingle upper-class etiquette with the legal code). And these were relatively restrained proscriptions compared to those coming from John Bircherites, segregationists, and “law-and-order” types. People were angry about everything: from the Vietnam War to apathetic consumerism. The center (“labor peace,” anti-Communism, and soft bigotry) was falling apart. Criminal and parapolitical violence got so bad that President Lyndon B. Johnson ordered a commission to study its causes and cures, and the New York Times Magazine ran opinions from public intellectuals on the question, “Is America by Nature a Violent Society?”

Some contemporaries were sure 1968 was a revolutionary moment. When that proved false, most were then sure it was at least the beginning of one. But it actually turned out to be the beginning of the end. And not only the beginning of the end, but the beginning of a counter-revolution. And the beginning of our political eternity.

What success a person gives to 1968—and the sixties, more generally—has a lot to do with blurry hindsight and historical sympathies. As Alexis de Tocqueville said, revolutions that succeed can seem like failures because they destroy what caused them. And whoever you think was right about what the goals should have been in the sixties (and whether those goals were achieved) will dictate how you feel about the political decade.

For example, the Weather Underground wanted “world communism”; the civil rights movement wanted the humiliation of being black in America to be replaced by the dignity of being a black American; and the counterculturalists wanted to popularize sex, drugs, and outsider status. What our “benign” system could accommodate from these demands it did—gleefully in the case of the counterculturalist ones. As Andrew Kopkind wrote in 1970, “The system didn’t change; it just accommodated the freaks for the weekend.” John Lennon complained in an interview that the sixties left the “same bastards running everything” and that nothing had changed except you now had “a lot of people walking around with long hair…and some trendy middle-class kids in pretty clothes.” Even Updike didn’t mind the “freaks” of his generation: “I was happy enough to lick the sugar of the counterculture,” he wrote in his memoir, “it was the pill of anti-war, anti-administration, anti-‘imperialist’ protest that I found oddly bitter.”

“Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan were two of the first Republicans to take advantage of how unpopular the peace, student, and feminist movements were with white working-class voters.”

In the end, defiance of suburban conventions in dress, music, and sex was more easily adopted by apathetic-consumerist society than it was by revolutionary politics. As the historian Richard Vinen observed in his broad study 1968: Radical Protest and Its Enemies: “The emphasis on production and investment [of the 1950s] had gone with a cult of hard work and self-denial, but, if it was to survive, capitalism needed to produce consumers as much as goods. The hedonistic culture of the late 1960s encouraged consumption.”

After the 1960s political symbolism got less political and more symbolic. Political symbols began representing not an allegiance to a cause but mere alienation and impotence (Che Guevara t-shirts of the early 2000s being the quintessential example). Symbols of resistance became emblems of surrender. This commercialization of politics weakened our political culture, stripping it of both its serious and its ironic qualities, leaving only the sensational (shock sells, after all) and the moralistic (as does guilt).

Yet what turned out to be perhaps even more counterproductive than the hedonistic excesses of the counterculture was the ideological feebleness of the “New Left.” The New Left distinguished itself from the Old Left in many ways, some good, some ridiculous. A cursory outline of the New Left’s ideological assumptions would be: (1) radical youth, not the working class, is the historical agent of progress; (2) the university, not the trade union, will be the “red base” for social change; (3) the act of rebelling is itself a political success; (4) power shouldn’t be taken because power necessitates victims; and (5) society is filled with authoritarian institutions, so myopically focusing on one (say, capitalist hierarchy) is reductionist and narrow-minded.

As British-Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm observed at the time, the New Left’s vernacular was different than the Old Left’s because the New Left’s was sociological rather than economic. “Capitalism” had been verbally usurped by “the system,” “the machine,” or “the power structure”; “alienation” stopped meaning the boss taking the fruits of your labor and started meaning the dissatisfaction you felt living in the suburbs.

In a tragic irony, the New Left eventually became everything it purportedly rebelled against. It was for action over conceptual thinking, yet its most enduring product is theoretical nonsense; it was against compromise with “the man,” yet embraced anti-Communism to get a voice in mainstream discourse; it opposed the conformity and thought control of the Old Left, yet ended up proliferating more cults than Christian talk radio; it was led by intellectuals, yet was woefully muddleheaded; it accused other activists of “selling out,” yet found the American Dream rather pleasant later in life.

Jerry Rubin, a founding member of the Youth International, ended up a venture capitalist saying things like, “Wealth creation is the real American Revolution.” Kathy Boudin, Weather Underground member, became a professor at Columbia after she served twenty years in prison for helping get two cops murdered. Tom Hayden, often thought of as the intellectual leader of the New Left, finished his political life by cynically using minority issues and his own radical legacy to justify supporting Hillary Clinton over Bernie Sanders. Time seems to have proved correct the Old Left’s critique of the New Left: white middle-class kids who would one day choose to stop playing revolution and get to go home.

Organizing around students rather than workers tended to stigmatize the former and dogmatize the latter. Students felt they couldn’t trust anyone with the wrong political lines, particularly on Vietnam, and workers were too easily turned off by the frivolous eccentricities of the students. The relationship hit its nadir when pro-war demonstrations started popping up in cities across the country. A leader of the Berkeley Free Speech Movement lashed out at the working people who participated, saying, “The next time some $3.90-an-hour AFL-type workers go on strike for a 50-cent raise, I’ll remember the day they chanted ‘Burn Hanoi not our flag,’ and so help me, I’ll cross their fucking picket line.” It became obvious that beneath the shared assumptions between workers and students on economic matters laid a volatile gorge of race, gender, and empire.

After the passage of the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968, the GOP-Dixiecrat coalition alchemized into the modern anti-liberal Republican Party. Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan were two of the first Republicans to take advantage of how unpopular the peace, student, and feminist movements were with white working-class voters, using those social antagonisms for electoral purposes. Reagan’s 1966 run for California governor was essentially a platform of anti-Berkeley-student-radicalism. Paranoia about race and sex was always exploitable to garner white conservative votes, but Nixon was the first politician to effectively turn that paranoid style of conservatism against white liberal professionals.

With Nixon’s “silent majority,” Republicans got white workers, whose sons were the ones dying and fighting in Vietnam, to support the invasion by turning them “anti-anti-war.” In surveys white workers were more anti-war than white professionals—polling higher, for example, in favor of immediate withdrawal—while still hating the anti-war movement, seeing it as a bunch of smug college students who were using their educational vocation to avoid getting drafted and who, as depicted in mainstream and right-wing coverage, hated the troops as much as they hated the war. The 1970 New York City Hard Hat Riot was union construction workers—supposedly irritated by displays of flag desecration—attacking anti-war protesters. Nixon later appointed one of the riot’s leaders, Peter J. Brennan, his secretary of labor.

“One can scoff at some of the tactics of the New Left, but its morality was simple: freedom is good, genocide is bad, and don’t root for the bully.”

The electoral alliance between labor politics and cultural liberalism was always tenuous and vulnerable, but in the sixties that alliance was turned into a truce (you support unions, we won’t make a fuss about our sons’ ponytails); but you don’t make truces with people on your side: you make them with enemies. Savvy reactionaries have been exploiting this political compromise ever since.

However, perhaps even more important to our contemporary politics than the hardhat-peacenik divide in America was the anti-immigrant sensibility being mobilized in Britain at the time.

Before 1962 Britain was not a nation-state but an empire; therefore it had subjects not citizens. In practical terms, that meant a man born in Lancaster was just as welcome to move to London as one born in Calcutta. All were in the commonwealth, all were subject to the crown. That obviously didn’t matter much so long as most of the commonwealth countries were poor and world travel relatively expensive. A Trinidadian wasn’t legally prohibited from immigrating to England—yet few did because of the cost of doing so. That is, until the fifties and sixties, when world travel became less expensive and England started to have more jobs than workers.

Although the number of immigrants moving into England was relatively low in the 1960s, there were still black and brown faces in towns where there once were none. Enter British parliamentarian Enoch Powell, whose doom-ridden “River of Blood” speech was delivered in 1968 to an annual meeting of conservative politicians and businessmen. Powell called for not only blocking immigrants from coming into England but for incentivizing those already there to go back to their native countries. He quoted novelistic tales of “charming, wide-grinning piccaninnies” stalking old English women down the streets. Although the children didn’t know English, they did know the word “racialist,” which they “chant[ed]” at white pedestrians. According to Powell, the new immigrants were overburdening the social services. English men “found their wives unable to obtain hospital beds in childbirth, their children unable to obtain school places, their homes and neighborhoods changed beyond recognition.” An “anonymous correspondent” told Powell he was worried that one day whites would be thrown in jail for expressing anti-immigrant or anti-black opinions (tell me that victimhood mentality doesn’t sound familiar?). “In this country in fifteen or twenty years,” said a Powell constituent, “the black man will have the whip hand over the white man.” On William F. Buckley’s Firing Line, Powell analogized immigration to an invasion (another “eternal” tune).

“As I look ahead,” Powell concluded his speech, “I am filled with foreboding; like the Roman, I seem to see the River Tiber foaming with much blood”—another insinuation that immigrants are comparable to invaders. British traditions and living standards weren’t being sought out (so Powell’s argument went), they were under attack.

Powell, who before his speech was mostly known for his scholarly affectations and “free-market” economics, gathered a considerable following in the British lower classes. Dock workers—usually militantly left-wing—went on a one-day strike in support of the speech. It didn’t help that just a few weeks beforehand, the dock workers had ended a failed ten-week strike that had received almost no help from the Labor Party. Nor did it help that the Labor administration of Prime Minister Harold Wilson was to the right of Powell and many other Tory ministers in its economic and foreign policies (for example, supporting the American occupation of Vietnam). Labor had no good response to Powell’s anti-immigrant demonology without challenging Britain’s existing employee-employer relations or without calling for a robust labor internationalism. The party did neither. Instead it continued to do what it was already doing, which was to “out-trump the Tories” (as Labor’s House Minister Richard Crossman put it) on restricting further immigration.

The political problems Nixon and Powell emphasized had been emphasized by plenty of rightists before them. What made their accentuations different was due partly to technological breakthroughs and partly to weak responses by their opponents. Mass media commercialized fear, hatred, and paranoia and standardized how those political emotions were channeled. The New Left’s sociological emphasis at first seemed more nuanced and inclusive but also seemed easy to steer in ways that reinforced power rather than challenged it. The nuance could even be turned against the inclusivity (e.g., white Freedom Riders questioning whether integration was a good thing because it was just drawing “some beautiful people into modern white society with all of its depersonalization”).

The sixties still haunt the present. Rightists weaponize the decade against liberals by charging them with foolishly embracing everything wrong with it (relativism and identity politics) or by charging today’s student radicals with betraying everything it stood for (free expression and individualism). Neither accusation is true. As many others have pointed out, if sixties radicals suffered from any moral affliction it was absolutism not relativism. Much of the violence and anarchy stemmed from white middle-class kids discovering that society’s real-world operations didn’t match its convictions. As was written in the Port Huron Statement (the New Left’s manifesto), “The declaration ‘all men are created equal…’ rang hollow before the facts of Negro life in the South and the big cities of the North. The proclaimed peaceful intentions of the United States contradicts its economic and military investments in the Cold War status quo.”

Soldiers stand guard near the US Capitol during the April 1968 riots following Martin Luther King’s assassination. (Source: Library of Congress)

Sixties radicals wanted their personal behavior to harmonize with their moral principles. If the Vietnam War was really genocidal, then what shouldn’t be done to stop it? If student-teacher relations were authoritarian, why listen to your teacher? If the government is really leading us to nuclear apocalypse, what good does it do to follow its laws? One can scoff at some of the tactics of the New Left, but its morality was simple: freedom is good, genocide is bad, and don’t root for the bully.

Minority identity politics (gay, black, Hispanic, indigenous, feminist, etc.) certainly became more relevant mid-century onward, but the notion that identity politics per se began in the sixties is ridiculous. As is the notion, commonly disseminated by podcast intellectuals, that the white identity politics championed by Trump supporters and crypto-fascists is in some way a reaction to minority identity politics. The truth is minority identity politics was a reaction to the majority identity politics of boys-only golf clubs, segregated schools, white Christian councils, and sodomy laws. The adoption of this manner of thinking and organizing might’ve been politically or intellectually shortsighted, but it certainly wasn’t the origin of something new; and, unlike its counterpart, usually moved toward the application of enlightenment principles rather than away from them.

The accusation that today’s student radicals are betraying the spirit of the sixties (a charge made against every subsequent generation of students) by protesting guest speakers, preferring student-faculty arbitration, or segregating themselves into “safe spaces,” is so dishonest (or ignorant) as to make a cat laugh. Heckling speakers was routine on college campuses, especially against politicians and military personnel. In February 1968, Columbia students interrupted a colonel’s speech by dressing in gorilla costumes and running around the lecture hall. While everyone was distracted, another student in the front row threw a pie in the colonel’s face. Students demanded student-faculty arbitration because they didn’t trust either the administration or the local police to give either the victim or the accused a fair hearing. When Columbia students occupied university buildings in 1968, they self-segregated with white students in one building and black students in another. Unsurprisingly, the administration tried to use this against them: telling the black students that the white students would capitulate to authority once their own demands were met, leaving the black students alone to defend the local community’s interests. And, just like today, there were plenty of pop-psychology explanations for why students were so recalcitrant: sheltered upbringings, no parental spanking, lax educational standards—literally the same nonsense that always gets said and written.

What’s most disturbing about the sixties is how little has changed today. The rhetorical methods of mainstream opinion and debate have hardly been tweaked. See if you tell whether this was written in 1966 or yesterday: “The best that may come of America’s current string of mass murders is a gun-control law that would have prevented none of them.” Or this: “Liberalism, almost by definition, needs victims to feel sorry for.” That you can’t is an indictment of our paint-by-numbers political culture. How they talked about “black power” is exactly how we talk about “Black Lives Matter.” How they talked about flag burning is exactly how we talk about NFL protests. How they talked about disorderly students is exactly how we talk about disorderly students.

Any social engagement from below is reprimanded either for its means or for its optics. The good liberal pundit, after all, always agrees with the ends, just not on any of the means by which you could possibly get there. Snyder’s “politics of eternity” doesn’t mean things stop. It means things go on forever. So what we had fifty years ago is the same today, only more so. The rich get richer and more powerful. The police get more militarized. The generals get more wars. The rest of us bobble along somewhere between conspiracy and disinterest.

Looking back at the sixties doesn’t tell us how we go forward from now. But it does show that the only way forward is to break out.