FIRST PERSON | From Young-Earth Creationist to Full-Time Humanist

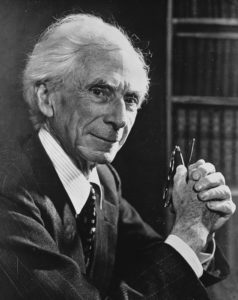

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Russell There’s a story in the life of the great humanist thinker Bertrand Russell that those who know him primarily as a philosopher may not have heard. His grandfather, Jack Russell, had been a popular prime minister of the British Empire under Queen Victoria, and his family name had Bertrand set to begin a promising political career if only he wanted it. He was recruited by the local Liberal Party Association, spoke at their meeting, and went into a closed strategy session with the organizers, fully expecting to be nominated for a seat in Parliament and there begin what was supposed to be a long and successful path to high office.

But first they had just one question. “We’ve heard rumors,” they said, “that you’re an agnostic. What are the odds of this getting out if you’re our party’s nominee?”

“Pretty good,” Russell replied.

“Well, would you consider going to church occasionally to keep up appearances?”

“No, not really,” be said.

That was the end of Russell’s political career, and it freed up a nearly century-long lifespan to devote to reshaping human thought as we know it, writing the best-selling book of the twentieth century on the topic of philosophy, and founding the modern secular movement (to say nothing of his contributions to mathematics, logic, and cognitive science).

This story, for reasons I’ll circle back to, always resonated with me.

I was homeschooled deep in the heart of Christian fundamentalism: young-Earth creationism, patriarchal theology, doomsday prepping, you name it. It was my whole identity, and my blossoming curiosity soaked it all up. I memorized books of the King James Bible and learned to preach as a teenager. And while I was considering a career in the ministry, I found my true love at the age of fifteen: politics.

In 2008 I traveled to California to volunteer for the Proposition 8 campaign, which amended the state constitution to define marriage as being between one man and one woman. It passed. When I was seventeen, I had made my rounds in conservative circles and started getting invited to speak at rallies and conferences as a sort of rising star for the new Tea Party movement that was sweeping the nation. They loved me because they loved a token young person who gave them hope for the next generation. At eighteen I moved to northern Virginia for my first full-time job at a consulting firm where I raised money for major Republican organizations and campaigns. At nineteen I earned my bachelor’s degree and went to a conservative Christian law school on a full-ride scholarship. At twenty I was working in Washington, DC, for a fundamentalist legal defense and lobbying organization.

Ironically, for that job I was on the steps of the Supreme Court the morning Proposition 8 was reversed. The initiative I had helped to pass in my first entry into politics was unconstitutional. I don’t know how many people can say they were in Sacramento in 2008 to see Prop 8 pass and in DC five years later to watch it go down, but I know how I felt watching both. And how I felt from one to the other could not have been more different. From pure ecstatic triumph as a teenager to a sick, guilty feeling at age twenty for being involved, mingled with secret relief that the cause I had worked for was lost.

See, there’s a funny thing about legal education. They teach you how to argue for both sides of a case, to see your weaknesses as your opponent’s strengths, and from that side of the chessboard, I played the game of constitutional law. I worked in First Amendment cases and became both a legal intern for an organization dedicated to advancing the religious right in the courtroom as well as president of their affiliated student organization. Naturally, when Ken Ham of Answers in Genesis came to my law school, I emceed for him. When he debated Bill Nye on the scientific legitimacy of creationism, I organized a debate watch party, ordered pizza, and livestreamed the whole thing, excited to watch creationism rise to a new level of legitimacy in media and the culture. And I watched Ken Ham, my childhood icon, get taken apart before my very eyes.

You have to understand I hadn’t thought about creationism since I was a teenager. Everything else, from politics to law to communications, had been built on the foundational truth claims of the Bible being an inerrant historical source and science textbook. All my activism and advocacy was to advance that agenda in the world, and the last thing I had time to do was revisit the underlying worldview.

But this was too important to ignore. Ken Ham was so breathtakingly, embarrassingly destroyed that I had to do something. My position was so poorly represented that night that I realized I had to research this issue. I was going to learn about evolution, astronomy, deep geological time, and everything else I could think of so that later, when I debated the Bill Nye’s of the world, I would represent young-Earth creationism better than Ham did.

I turned to philosophy to wrestle with the foundational questions. I stopped taking the seminary classes that had filled my summers, losing interest in my longtime passion to mobilize churches to collaborate in political causes. I turned all of that interest and academic energy into learning the science that I had never been expected to care about.

It came to a head in the summer of 2016. I was looking for any reason I could find to hold onto faith so that life could go on.

I was in a Chick-fil-A in central Texas where I was working for a Republican state campaign. My then-fiancé was in Asia for the summer doing missionary work, so I had almost no opportunity to discuss my journey with her.

I remember vividly the instrumental Christian music the restaurant was cleverly playing, covert enough that a nonbeliever needn’t be offended by the cultural tropes of Christianity but that a believer would immediately know. As the songs played, my head filled in the words, drudging up every fundamentalist sermon, every pseudo-scientific talking point, and the hundreds of King James Bible verses I had committed to memory.

In my hand was a copy of Baruch Spinoza’s book about deism, which I had been looking forward to reading as a sort of culmination of my search for an intellectually honest kernel to rational religion. Maybe I thought I could salvage the core. Maybe I could amputate some of the baggage and keep Christianity and the validation I needed to move forward in life.

Spinoza writes about a generic, deistic God all major religions catch glimpses of, and describes this presence so vaguely that God essentially becomes a symbolic word for people like Einstein to borrow to refer metaphorically to the unknown. Spinoza’s God, indistinguishable from the universe itself, was exactly the validation I’d been looking for, and when I found it, I realized it was completely meaningless. It made no sense compared to honesty.

I’ve only begun learning about the incredible opportunities and responsibilities that come with professionalizing the secular movement at the local level.

I lost it. I dropped my book, went into the Chick-fil-A men’s room , sat on the toilet, and bawled my eyes out for an hour and a half. I was, I finally admitted to myself, an atheist, a humanist, and a progressive (in more ways, I would soon learn, than I was prepared to understand). Everything that my old worldview had made clear to me about my place in the universe and the purpose of my life was gone. Adrift on a sea of chaos, I called my fiancé in Korea and left her a voicemail telling her what had happened and begging her not to leave me as her faith said she must.

She didn’t. And our journeys, in parallel directions, have made us both better people into our marriage and given me the support needed to leave my conservative career and start over as a professional progressive activist, bringing my intimate knowledge of the other side to bear on the right side of history.

When I fell back on my wife’s financial support, I became a full-time campaign volunteer, slowly working back up to paid consulting. I knew I had to rebuild my network from scratch if I wanted to keep doing what I loved.

I started searching for my dream job where I could harness the power that I’d seen on the religious right, where the whole momentum of my professional life was leading. Churches surround human beings with communities of support that teach, inspire, and mobilize their collective influence for what they believe is good. Having changed what I believed was good, I made it my mission in life to find or build a community around humanist values and mobilize it to fill the void left by the collapse of traditional religion.

In the 1910s, Bertrand Russell faced a world where no humanist who was honest about it could hope to serve their country in high office. And even a couple years ago, when I came to grips with my nonbelief, it really looked like nothing had changed. In just the past few years, though, we’ve seen great progress on this front, with more people in leadership positions and even government being more open about their lack of affiliation with a faith tradition. The incredible organizers at the Humanist Society of Greater Phoenix took their leap of faith by creating a full-time executive director position, among the first in the nation of its type. In my first few months at this job, I’ve only begun learning about the incredible opportunities and responsibilities that come with professionalizing the secular movement at the local level. If it succeeds, there is a nation full of empty churches and former fundamentalists ready to take humanism to a scale that will change the world.