More Light Than Heat The Importance of Education in Coping with Climate Change

The Climate Book, a massive anthology compiled by Greta Thunberg—the young Swedish environmental activist who won global fame after she launched her School Strike for Climate in 2018—offers a compendious treatment of climate change. Its five parts offer to explain how climate works, how our planet is changing, how it affects us, what we’ve done about it, and what we must do now. The hundred-plus contributors include scientific luminaries such as Michael E. Mann as well as social scientists such as Naomi Oreskes, climate journalists such as Elizabeth Kolbert, and even cultural icons such as the novelist Margaret Atwood. Publishers Weekly described it as “a comprehensive and articulate shock to the system,” while the reviewer for Yale Climate Connections praised it as “the most ambitious, wide-ranging, and hard-hitting collection I have ever encountered.” And yet nowhere in the book’s eighty-four chapters spread over 464 illustrated pages is there a sustained discussion of climate change education.

The omission is remarkable. True, climate change education is often overlooked in discussions of climate policy. For example, a recent draft of the Fifth National Climate Assessment—intended to enhance the nation’s ability to anticipate, mitigate, and adapt to changes in the global environment—contained only a scattered and unsystematic discussion of the issue. But such neglect is unfortunate, because climate change education is a critical component of any plan for responding to the disruptions due to climate change. Today’s students will spend the rest of their lives on a warmer planet, mainly on account of the actions—and inactions—of their elders. A youth slogan in circulation offers a candid, if unkind, reminder to adults: “You’ll die of old age; I’ll die of climate change.” Sure to be facing the challenges of a warming planet, the rising generation needs to be equipped with the knowledge and the knowhow to cope with those challenges. Thunberg, who recently turned twenty, might have been expected to agree.

The level of support for climate change education in the United States is high. About seventy-seven percent of Americans agree, strongly or somewhat, that schools should teach about the causes, consequences, and potential solutions to global warming, according to a 2021 estimate from the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Similarly, about seventy-seven percent of Americans regard it as very or somewhat important for elementary and secondary school students to learn about climate change, according to a 2019 study from Teachers College, Columbia University. Unfortunately, individual willingness to express support for climate change education to a pollster is not easily translatable into social resolve to provide adequate climate change education in the formal educational system. There are systemic obstacles to climate change education in the United States, which are based in part on cognitive, emotional, and ideological obstacles to individual understanding and acceptance of climate change.

“I don’t get it”

It is not altogether surprising that Americans tend not to understand climate change. In a 2016 paper published in Topics in Cognitive Science, Michael Ranney and Dav Clark discuss a study in which participants were asked to explain the central mechanism of global warming in a few sentences. The results were grim, suggesting that “virtually no Americans”—only twelve percent—“know the basic global warming mechanism,” that is, the greenhouse effect. What the participants were unable to explain is that greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, absorb heat reradiating from the earth’s surface; increasing the concentration of such gases in the atmosphere, a consequence of burning fossil fuels, thus tends to increase the global temperature. Encouragingly, however, Ranney and Clark also found that a modicum of “physical–chemical climate instruction durably increased such understandings” and moreover also increased the acceptance of climate change. Ignorance can be alleviated.

About seventy-seven percent of Americans agree, strongly or somewhat, that schools should teach about the causes, consequences, and potential solutions to global warming.

But it isn’t always easy to alleviate ignorance, especially with regard to a phenomenon like climate change that conflicts with what the psychologist Andrew Shtulman calls “intuitive theories” of how the world works. Imbued by nature and nurture, these theories are deeply embedded in human cognition and are consequently difficult to dislodge. In his 2017 book Scienceblind, Shtulman suggests that although the intuitive theory of the earth regards the planet as eternal and unchanging, “conceptualizing the earth as a dynamic system changing over deep time is critical…for understanding its climate.” A similar intuitive theory clashes with the fact that seemingly imperceptible and infinitesimal causes—such as increases in greenhouse gas concentration, measured in parts per million—are capable of producing significant, even catastrophic, effects. Even the scientifically literate find themselves feeling the sway of these intuitive theories when they are not attentive.

A further cognitive obstacle to understanding climate change is the prevalence of disinformation. With regard to climate change as with regard to any topic, those who are not experts themselves rely, not unreasonably, on information from those whom they take to be experts. That’s usually not a tremendous problem—unless there are incentives to disseminate false information and promote fake experts. In the case of climate change, as Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway relate in their 2010 book Merchants of Doubt, the oil and gas industry recruited a handful of prominent scientists, who previously disputed the scientific consensus on such topics as tobacco, acid rain, and ozone depletion, to misrepresent anthropogenic climate change as scientifically controversial. Today, disinformation about the scientific consensus on climate change, as well as myths pertaining to a plethora of specific aspects of the topic, continues to percolate through certain segments of mainstream, online, and social media.

“I don’t like it”

Not all of the obstacles to understanding climate change are cognitive in nature: there are also emotional obstacles. Learning about the causes and consequences of climate change often engenders negative feelings, such as guilt about contributing to the causes, worry about the disruptive consequences, and despair about the prospect of mitigating or adapting to the consequences. Common ways of coping with such negative feelings include avoidance, distancing, and denial: trying to minimize engagement with the topic of climate change; regarding the consequences of climate change as spatially or temporally remote; and rejecting or doubting the scientifically ascertained facts about climate change. These all interfere with understanding and accepting climate change (which is why conscientious educators typically discuss solutions to climate change, to encourage students to cope with these negative feelings by concentrating on problem- solving instead).

And there are also ideological obstacles to acceptance of climate change. A 2022 poll from the Pew Research Center found that “religiously affiliated adults and those who are highly religious are more likely than those who are religiously unaffiliated or have lower levels of religious commitment to say that the Earth is getting warmer mostly due to natural patterns, or that there is no solid evidence the Earth is warming.” But it would be too fast to infer that religion as such is a barrier to accepting climate change. A 2016 study by Elaine Howard Ecklund and her colleagues published in Environment and Behavior found that although there was a correlation between religiosity and rejecting climate change in the American public, it vanished, almost without exception, when they controlled for political ideology. The exception was that evangelical Christians were significantly more likely to reject climate change than the religiously unaffiliated, even controlling for political ideology.

So political ideology is a powerful barrier to accepting climate change, whether it is measured in terms of a scale from extremely liberal to extremely conservative, as in Ecklund’s study, or in terms of party allegiance. There is a broad and widening gap between Democratic and Republican attitudes toward climate change. A 2019 poll from the Pew Research Center found that eighty-four percent of liberal Democrats but only fourteen percent of conservative Republicans agreed that human activity contributes “a great deal” to global climate change. It’s a far cry from the days of George H. W. Bush, who in a 1988 campaign speech declared, “Those who think we are powerless to do anything about the greenhouse effect forget about the ‘White House effect’”—though once in the White House he acquiesced to the forces of climate change denial. For the majority, of course, the connection between political ideology and attitudes toward climate change is less a matter of considered judgment and more a matter of tribal loyalty.

Climate change in the American educational system

The obstacles at the individual level to understanding and accepting climate change are ubiquitous, but they are of particular concern in formal secondary education, where the bulk of Americans learn about climate change. On the one hand, the complex concepts involved in climate change are generally beyond the capacity of primary students, so it’s appropriate to defer climate change instruction as such until middle and high school. (Yet it is desirable for primary students to start to erect the scaffolding required for later learning about climate change, including such basics as the fact that sunlight warms Earth’s surface.) On the other hand, although a majority of Americans graduate from high school or complete a GED, only a minority graduate from college, so it’s inappropriate to defer climate change instruction until college—especially because all Americans, college graduates or not, will be increasingly faced with the task of making individual and social decisions about issues to which climate change is relevant.

Only twelve percent of Americans know the basic global warming mechanism, that is, the greenhouse effect.

Within formal secondary education, the most natural place to lay the foundation of climate literacy is in science classes (although there is a movement to expand it elsewhere). Accordingly, professional societies of science teachers have issued position statements acknowledging the scientific consensus on anthropogenic climate change and endorsing the legitimacy and the importance of teaching climate change in the science classroom. The pioneer was the National Association of Geoscience Teachers (NAGT) in 2009. The current version of its statement describes teaching climate change science as “a fundamental and integral part of earth science education,” adding that “NAGT strongly supports and will work to promote education in the science of climate change, [including] the causes and effects of current global warming.” By now, there is a clear agreement among such societies, including the National Science Teaching Association, that climate change education is a crucial part of science education.

But curriculum and instruction in American K–12 education is highly decentralized. The federal government plays virtually no role. The states (as well as the District of Columbia and the larger U.S. territories) have adopted science standards, which specify what knowledge and abilities students are expected to acquire in the course of their science education. But decisions about curriculum and instruction are primarily the responsibility of local school districts—of which there are about 13,500, ranging from the City School District of the City of New York, with over 1.1 million students, to the Bois Planc Pines School District in Michigan, with four—and individual schools and teachers within those districts. And these districts are under the control of locally elected school boards and, at a distance, locally elected state legislatures. As a result, there is substantial variance in climate change education in American science education—often reflecting doubts about climate change driven by political ideology.

Ideology attacks climate change education

Policymakers in the grip of ideology have sporadically attempted to interfere with climate change education. In a common type of legislation that purports to allow teachers to present the “strengths and weaknesses” of supposedly controversial topics in science, global warming is often cited along with biological evolution, the chemical origins of life, and human cloning—although only one such bill, Arizona’s Senate Bill 1213 from 2013, was aimed primarily at climate change. As science standards have increased in importance, they have become the targets of such interference. Idaho’s legislature successfully blocked the adoption of new science standards from 2016 to 2018 largely because of objections to their inclusion of climate change. It isn’t only legislators who have tried their hand: state boards of education in Texas and West Virginia and state departments of education in Arizona and New Mexico have also sought to weaken the treatment of climate change in science standards.

Even in the absence of such attacks, there is evidence that the treatment of climate change was compromised in science standards in a number of states, evidently in order to allay ideologically motivated rejection of climate change. Where the widely adopted Next Generation Science Standards expect middle school students to examine evidence that human activities and natural processes have caused a rise in global temperatures, for example, South Dakota’s standards only suggest that such factors “may have” caused a rise, while Missouri’s standards describe what these factors caused not as a rise but as a change. Worse yet, in a 2020 study of the treatment of climate change in science standards conducted by the National Center for Science Education and the Texas Freedom Network Education Fund, five states—Mississippi, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, and West Virginia—were found to have standards that misrepresent climate change as a matter of scientific debate.

Below the level of state policy, the most conspicuous type of ideological attack on climate change education is the distribution of propaganda to students and teachers in public schools. Such propaganda sometimes originates with industry sources—such as the Oklahoma Energy Board, which produced and circulated “Petro Pete’s Big Bad Dream,” in which the title character realizes that “having no petroleum is like a nightmare!”—and sometimes with climate-change-denial outfits, such as the Heartland Institute, which in 2017 mailed unsolicited packets of climate change denial propaganda to a claimed 350,000 public school science teachers across the country. (A Massachusetts teacher who dissected the Heartland material with his elementary class reported a student’s apt description: “stupid book of wrongness.”) While it is unclear to what extent these efforts have accomplished their purpose, it is encouraging that in its latest campaign, in 2023, Heartland reportedly mailed to only 8,000 teachers.

Inertia afflicts climate change education

A protestor at the Global Strike for Climate Justice in Toronto.

As if ideology weren’t enough, there’s also inertia. Today’s teachers typically lacked the opportunity to learn about climate change during their own education. In a nationally representative survey of public middle and high school science teachers conducted by researchers at the National Center for Science Education and Penn State in 2014–2015, more than half of the respondents reported having never taken a course in college that devoted even a single class session to climate change; more than seven in ten reported having never taken such a professional development course. Not coincidentally, such teachers were less likely to emphasize the scientific consensus on climate change and more likely to present supposed alternative perspectives as scientifically credible in their classrooms. Only a few state legislatures—those of Washington, California, Maine, and most recently New Jersey—have passed laws appropriating funds to prepare their public science educators to teach climate change effectively.

Resources for teachers are also lagging. Until Pennsylvania adopted improved science standards in 2022, its science teachers were guided by a set of standards adopted in 2002, from which climate change was simply absent, and which therefore received the grade of F in the 2020 study of the treatment of climate change in science standards. Similarly with textbooks. In a 2015 study published in Environmental Education Research, Diego Román and K. C. Busch investigated the treatment of climate change in four sixth-grade science textbooks published in 2007 and 2008 and adopted for statewide use in California, concluding, “The message was that climate change is possibly happening, that humans may or may not be causing it, and that we do not need to take immediate mitigating action.” They ruefully added, “The creation of textbooks is a slow process, and once adopted, textbooks tend to stay in classrooms long after their contents are proven inaccurate.”

Humanists have played a vital role in reconciling Americans to evolution and the need for evolution education—not primarily because they were eager to counter religious opposition but because they valued science and education. For the same reason, humanists should support climate change education.

Finally, climate change is in effect homeless in American education. The most natural place to teach and to learn about climate change in secondary education is a high-school-level earth science class. But owing to a historical neglect of the earth sciences in American education, such classes are rare. Estimates of the percentage of graduates who take earth science classes in high school vary, but twenty-five percent is probably the limit. Only eight states require the study of earth science concepts at the high school level and only two states require students to take a year-long class in earth science or environmental science to graduate, according to a 2018 report from the Center for Geoscience and Society. Even if the study of climate change is broadened beyond science classes to the rest of the curriculum—a strategy pioneered by New Jersey in 2020 thanks to the advocacy of the Garden State’s First Lady, Tammy Murphy—the need for a comprehensive scientific treatment of climate change at the high school level is still urgent.

◊

The American Humanist Association’s (AHA) 2017 resolution on climate change recognizes that “greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel combustion…are a leading cause of climate change” and that “drastic global climate change is a challenge facing all populations around the world,” and it consequently affirms the AHA’s support for a variety of policies intended to help mitigate and adapt to the consequences of climate change. These are all themes appropriate for any scientifically informed discussion of climate change policy, such as Greta Thunberg’s The Climate Book. But like The Climate Book, the AHA’s 2017 resolution—and also, apparently, the efforts to continue it, such as the Humanist Environmental Response Effort (HERE) for Climate Initiative—fails to address the importance of climate change education explicitly. Yet it would be altogether in the spirit of humanism, which values science, education, and the welfare of both humanity and the global environment, to do so.

The American Humanist Association’s (AHA) 2017 resolution on climate change recognizes that “greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel combustion…are a leading cause of climate change” and that “drastic global climate change is a challenge facing all populations around the world,” and it consequently affirms the AHA’s support for a variety of policies intended to help mitigate and adapt to the consequences of climate change. These are all themes appropriate for any scientifically informed discussion of climate change policy, such as Greta Thunberg’s The Climate Book. But like The Climate Book, the AHA’s 2017 resolution—and also, apparently, the efforts to continue it, such as the Humanist Environmental Response Effort (HERE) for Climate Initiative—fails to address the importance of climate change education explicitly. Yet it would be altogether in the spirit of humanism, which values science, education, and the welfare of both humanity and the global environment, to do so.

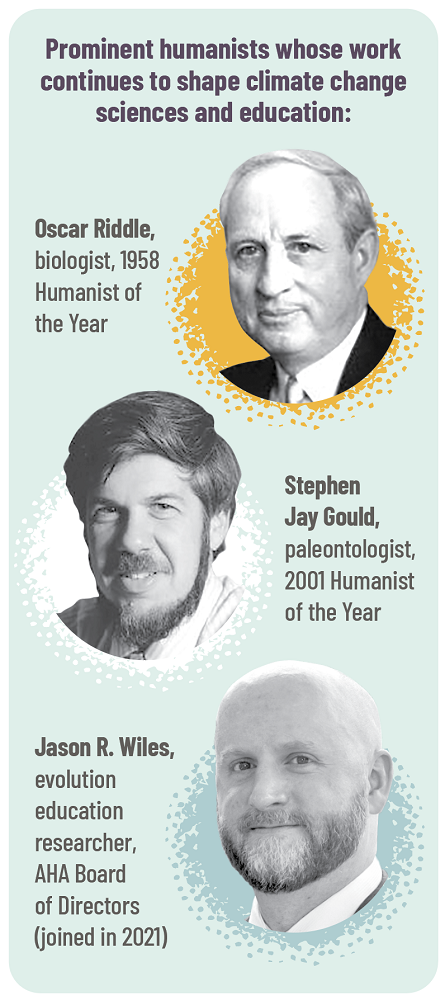

Evolution affords a useful parallel. As soon as evolution entered the public school classroom, evolution education became a matter of social controversy, as in the Scopes trial of 1925. Although the controversy has not yet subsided, evolution became the majority view among Americans around 2016, according to a 2022 study by Jon D. Miller and his colleagues published in Public Understanding of Science. From Oscar Riddle, the biologist who won the AHA’s Humanist of the Year Award in 1958, through Stephen Jay Gould, the paleontologist who received the same honor in 2001, to Jason R. Wiles, the evolution education researcher who joined AHA’s board of directors in 2021, humanists have played a vital role in reconciling Americans to evolution and the need for evolution education—not primarily because they were eager to counter religious opposition but because they valued science and education. For the same reason, humanists should support climate change education.

Although The Climate Book fails to provide a sustained discussion of climate change education, the heading to part 5 is supportive: “The most effective way to get out of this mess is to educate ourselves.” In the text, Thunberg explains, “I firmly believe that the most effective way for us to get out of this mess is to educate ourselves and others (a bit ironic, since the idea of school strikes is based on skipping school, but still). Because once you understand the situation we are facing, once you get a sense of the full picture, you will more or less know what to do.” As a statement of the importance of climate change education, it’s commendable—but too limited. In order for us to cope with the challenges of the climate crisis—to get out of this mess, in Thunberg’s words—it is not enough for us to educate ourselves and others. We must ensure that teachers have the opportunity to teach about climate change accurately, honestly, and thoroughly, because their students need to learn it.